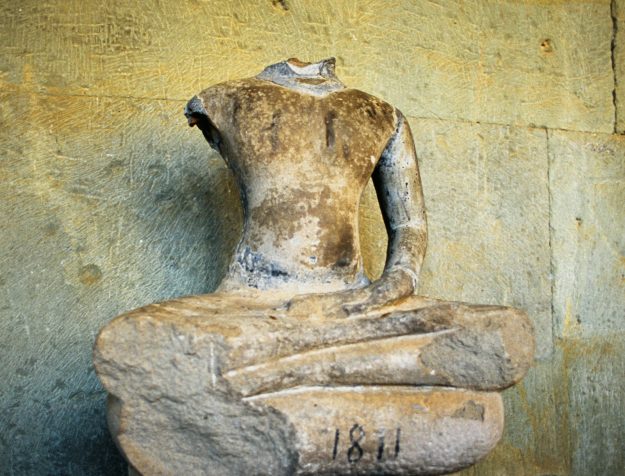

In early 2000, a statue of Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion, vanished from its altar at the Devisthan Kundalpur temple in Kurkihar, India. The figure had been enshrined at the temple for nearly 1,200 years. It reappeared in 2018—in the sales catalog of a French art dealer.

Situated on the pilgrimage route to Bodhgaya, the village of Kurkihar is of great interest to historians and art collectors alike. Between the 9th and 12th centuries, it was a major Buddhist site, as archaeological finds there attest. In 1930, it yielded the “Kurkihar hoard,” more than 220 relics unearthed from the ruins of a monastery, most of which are now held at the Patna Museum in India’s state of Bihar. But the area’s rich Buddhist heritage has also made it attractive to looters and underground art dealers. The Patna Museum itself was a victim of antiquities theft in 2006.

Antiquities trafficking has been rampant in India for decades, and Buddhist relics, popular in foreign markets, make up a large portion of these illegal sales. The rapid expansion of digital marketplaces has accelerated black-market international trade in recent years, and authorities have fought to keep up.

The loss of irreplaceable cultural and religious objects and the lack of decisive government action led to the launch of repatriation efforts by citizen activists. S. Vijay Kumar, an independent investigator, cofounded the India Pride Project in 2014 after seeing how brazenly Indian artifacts were being traded on the open market. Kumar’s group is now a global organization with more than forty employees. Its hashtag slogan is “#BringOurGodsHome.”

“Even though India has its own antiquity legislation from 1878, it was useless,” Kumar told OpIndia, an Indian news site. The 1970 UNESCO Convention, which officially prohibits antiquities trafficking worldwide, also made little headway against the growing trade. “India was not serious about any of this,” Kumar said. He took matters into his own hands and now works directly with the Indian government and law enforcement.

In 2022, after a search lasting several years, Kumar’s team retrieved the Kurkihar Avalokiteshvara with the help of a lawyer, Christopher A. Marinello. The object was found in Milan; its new owner surrendered it to the Indian consulate in Italy upon seeing a photograph of the sculpture on the altar of its original temple.

Work is also under way in the markets where antiquities are bought. In the United States, the Manhattan District Attorney’s office opened its own Antiquities Trafficking Unit in 2017. The unit collaborates with independent investigators such as Kumar to detect and deter illegal antiquities purchases in New York’s art market.

The DA’s office launched an investigation into the Manhattan-based art dealer Subhash Kapoor, one of the world’s most prolific antiquities smugglers. Kapoor is believed to have run a multinational enterprise that trafficked South Asian antiquities from across the globe for thirty years. He maintained an air of legitimacy by creating false paper trails, including forged provenance records, to reassure his customers. Kapoor was convicted of smuggling in India in late 2022 and sentenced to ten years in prison. He is now awaiting trial for a separate case in New York following a 2019 indictment.

In October 2022, the DA’s office announced the return of 307 antiquities to India, valued at nearly $4 million. Of those, 235 were seized in connection with Kapoor’s smuggling enterprise. In total, the DA’s office has seized more than 2,500 looted artifacts linked to Kapoor worth an estimated $143 million.

Private purchases of smuggled antiquities are relatively straightforward to correct. More complex is when looted objects find their way into the permanent collections of major museums, a relatively common phenomenon. In 2021, New York’s Rubin Museum of Art learned that two Nepali artifacts within its collection had been smuggled from religious sites and sold under forged provenance documents. Citizen activists from Lost Art of Nepal and the Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign discovered the items and reported their findings online. The two pieces are a 17th-century wooden carving from the Yampi Mahavihara temple complex in Lalitpur, Nepal, and a 14th-century carving of an apsara (female spirit) from the Itum Bahal monastery in Kathmandu. The Rubin voluntarily returned these objects to Nepal in 2022.

In an email correspondence, the Rubin’s executive director, Jorrit Britschgi, shared that the return of these two objects has made museum officials acutely aware of the need to dedicate resources to provenance research. The museum has engaged a Nepali art historian as well as US-based provenance experts to support these efforts. It is also five years into a full provenance review of its entire collection.

At the same time, Britschgi laments public discourse around repatriation that generalizes claims about objects based purely on their geographic origins. Britschgi believes the Rubin can play a useful role in the resolution of cultural property issues, but that a “monolithic treatment” of collections can lead to “ignoring the complicated nature of history,” he said.

“Each case is different. And the situation can be much more nuanced and complicated than assumed,” Britschgi argues. “We must ask questions such as: Who made the object? Who was it made for? When was it made? What type of object is it and what was it used for? Was it private property or public? Was it transportable or part of a fixed structure? How did it change hands over time and under which circumstances? How did it enter our collection? Who should it belong to today?”

Founded relatively recently, in 2004, the Rubin Museum has dedicated its resources to the preservation of Himalayan art. The museum was even blessed by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, who visited soon after it opened and who is understandably invested in Himalayan cultural preservation.

For older institutions such as the British Museum, the question of repatriation is more convoluted. Museum directors find themselves in the challenging position of leading institutions whose very foundations are entangled with the darker narratives of empire, colonization, and cultural exploitation. They were founded in an age when looting was not only legal but also integral to the European project of possessing other cultures in their entirety.

The commonly held view of museums today is that they are benign institutions aimed at public education, preserving the global cultural heritage for the common good. However, as Shimrit Lee notes in her 2021 book, Decolonize Museums, this perceived neutrality of museums is a “testament to the extent that the histories of museum spaces have been buried.” Lee points out that the bulk of the British Museum’s collection was assembled by explorer Sir Hans Sloane, whose global expeditions were funded by a sugar plantation in Jamaica operated by enslaved people. Similarly, the Louvre in Paris boasts an Egyptian antiquities collection largely stocked from Napoleon’s invasion of the Middle East. As is often the case, it’s these very exhibits that attract the most visitors, helping fund the institutions.

Even when museums list the provenance of items on display, critics decry the glossing over of difficult narratives. “Wall texts often tell neutral, authoritative narratives of the objects displayed,” Lee writes, “but that passivity fails to reckon with the extractive nature of colonialism by which most of the Global South was robbed of culture, resources, and people in plain sight.” For Lee, repatriation is not simply about returning stolen objects. It’s about the restoration of dignity.

While antiquities trafficking today is primarily motivated by financial gain, the historical precedent for looting as a justifiable act seems to have paved the way for these acts to continue and further blurs the boundaries between preservation and exploitation.

English scholar and collector Douglas Latchford accumulated an enormous collection of ancient Khmer treasures from Cambodia beginning in the 1970s. Mostly Hindu and Buddhist sculptures, his collection was among the largest repositories of Khmer art in the world. Latchford also cowrote scholarly books on his findings, becoming an internationally renowned expert on Khmer antiquities. He was even formally honored by the Cambodian government as an advocate of its nation’s cultural heritage in 2008. But in 2019, Latchford was charged with smuggling Cambodian relics, falsifying provenance documents, and selling the relics for personal profit. As reported by the New York Times, Latchford defended himself, saying, “If the French and other Western collectors had not preserved this art, what would be the understanding of Khmer culture today?”

“These objects are not just decorations, but have spirits and are considered as lives.”

Many of these items have since wound up in major museums. While their true provenance is still unclear and perhaps unknowable, some critics continue to press for a full investigation. “These objects are not just decorations, but have spirits and are considered as lives,” Phoeurng Sackona, the Cambodian minister of culture and fine arts, told the Washington Post in 2021. “It is hard to quantify their loss to our temples and country—losing them was like losing the spirits of our ancestors.”

In 2002, eighteen major museums signed the Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums, attesting that objects of cultural heritage—no matter the country of origin—are considered part of the heritage of the entire human story. But critics argue that claims of “universal heritage” are smokescreens to deter close examination of museums’ prized collections Additionally, such major museums, mainly in the West, benefit only the communities that are in close proximity to them, not the items’ countries of origin.

In response to this issue of accessibility, Roshan Mishra, director of the Taragaon Museum in Kathmandu, started an online initiative to educate the citizens of Nepal about their cultural heritage and to build awareness around the ongoing problem of antiquities trafficking. The Global Nepali Museum showcases artworks of Nepali origin that are presently housed in permanent collections outside Nepal, including at the Rubin. The goal of the project is to bring together all Nepali works under one domain as a resource for students and researchers.

There are discussions in India and the UK, but no current efforts to create a museum dedicated solely to British colonialism. “It’s not a matter of being woke or a matter of being fashionable or trendy,” historian William Dalrymple wrote in the Guardian. “It’s being realistic about some of the really terrible things that happened in our past and teaching them to our children.” In a similar vein, Shashi Tharoor, a member of India’s parliament, proposed that the Victoria Memorial in Kolkata be converted into a museum displaying the atrocities of the British Raj.

As public demands for accountability increase, more museums are having to come to terms with the changing cultural climate. Rubin executive director Jorrit Britschgi sees this moment in history “as an opportunity for museums to rethink our role, to think critically about the power of objects and storytelling, to foster a bold culture of open conversation, and to lean into the hard questions of our time.”

Correction: This article originally stated that the Rubin Museum helped launch Himalayan Art Resources and Treasury of Lives, when in fact it was the Shelley and Donald Rubin Foundation that helped launched these initiatives.