Old age is a time of loss. We lose much of the strength and endurance of our body and our senses. We lose friends, family, acquaintances, colleagues. The world that had become so familiar becomes unfamiliar. We lose assurance in the reliability of our memory and our mental faculties. Thus we enter a realm of deep and pervasive uncertainty. Novel pains make even this body an unfamiliar dwelling place. There is no resolution to our progressive instability. Much that we have relied on comes apart, and we find ourselves in a terrain increasingly unknown.

Our minds, however, continue moving onward. We cannot say where we are going or what we are seeking, yet mind never stops. Perhaps we seek those things that meant so much to us in the past. But we also seek new ways of inhabiting our evolving circumstances. We know that we cannot go back. We are in a state of new isolation. So we look for something more fundamental, some kind of simpler, more settled awareness that stays with us. And some way of sharing this.

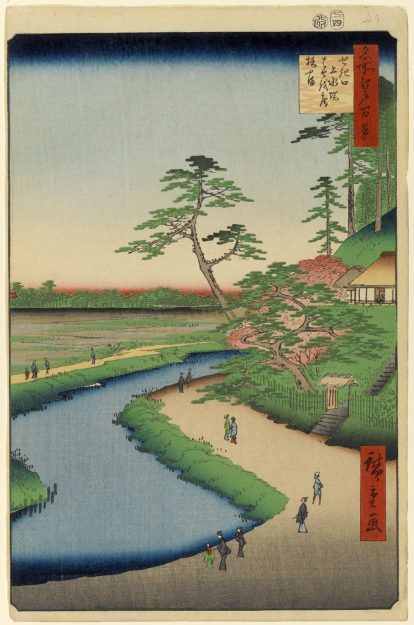

In 1689, the renowned poet and Buddhist practitioner Matsuo Basho journeyed on foot through northern Japan’s mountainous inner provinces. He was forty-five years old (quite old by the standards of the time) and not in good health. He and his friend Kawai Sora spent the spring and summer months wandering along arduous pathways as they visited remote villages and temples. This journey was the basis for Basho’s travel diary, a small volume that he worked on for the next five years and eventually published in the year of his death. It is one of the most famous books in Japanese literature, and it encompasses Basho’s outer journey and his inner reflections. It is very much a book of journeying in old age.

We cannot say where we are going or what we are seeking, yet mind never stops.

The Japanese title of the book is Oku-no-Hosomichi: Oku, meaning “inward,” “distant,” “most far-reaching intention”; no meaning “of”; and Hosomichi, meaning “narrow pathway” or “trail.” Sam Hamill’s superb translation cannot be recommended too highly. He titles Basho’s masterpiece Narrow Road to the Interior, pointing to the text’s inner and outer dimensions. Those of us in our old age who now share the travels of this man so distant from us in space and time may well discover a close companion. As Hamill has noted, Basho’s poems often suggest elemental loneliness: “wabi, an elegant simplicity tinged with sabi, an undertone of ‘aloneness.’” It is not so much that we should regard Basho as an advisor or guide in our losses and uncertainties; rather, in the loneliness that is unique to old age, we can find in Basho a companion with whom to share the innumerable moments of loss and discovery that aging brings.

Here are some excerpts and responses, selected and written not as wisdom or advice or method, but as observations of companionable wanderers chatting or writing letters to each other.

The Moon and Sun are eternal travelers. Even the years wander on. A lifetime adrift in a boat, or in old age leading a tired horse into the years, every day is a journey, and the journey itself is home. From the earliest times there have always been some who perished along the road. Still I have always been drawn by windblown clouds into dreams of a lifetime of wandering.

But this is not a world serving as the backdrop for an individual moving according to intention. Here is an unfixed being moving amid worlds of change. Existence, home, environment, past and future, life and death, all are continuously in flux. Perhaps we are more aware of this in old age because now we know that our control over our circumstances and our future is diminishing. We are being shaped and unraveled, carried here and there by forces we do not know. These unsought movements and changes will reveal unsuspected beauty and wonder. But they are groundless. It requires daring to look.

Those who remain behind watch the shadow of a traveler’s back disappear.

As we watch those who are becoming old, is it like this? Are we who watch them age simply left behind? Are we, the aging, disappearing from the sight of those who are still young?

My hair may turn white as frost before I return . . . or maybe I won’t return at all. . . . The pack made heavier by farewell gifts from friends. I couldn’t leave them behind.

Here the wanderer is still thinking about how he will appear on his return, and he cannot abandon the kind offers of those he’s left behind, burdensome though these may be. Aging—it is the same.

Continuing on to the shrine at Muro-no-Yashima, my companion Sora said, “This deity, Ko-no-hana Sakuya Hime, is Goddess of Blossoming Trees and also has a shrine at Fuji. She locked herself inside a fire to prove her son’s divinity. Thus her son was called Prince Hohodemi—Born-of-Fire . . .”

Japanese deities, or kami, are not just spirits of sun or sea or oak or mountain stream. Kami in the broad sense can refer simply to that which is awe-inspiring, fiercely provocative, or strange and haunting. In this sense kami can be described as experiences—clear and distinct moments in which perception of a place or thing merges with a specific syllable sound or word and a specific feeling. A unique moment of living intensity. Such an intensity, like that of the blossoming tree, is not necessarily locked in place. The myth describes the pregnant Ko-no-hana Sakuya Hime—a recently betrothed kami princess who had been accused of infidelity with a mortal—setting fire to her birthing hut. When she emerges with her newborn son unscathed by flames that would surely claim any mortal, the rumors are dispelled. Yet her moment of supreme conviction persists, crystallized in a new kami: “Born-of-Fire.”

This scene is the first moment where Basho and his friend are not concerned with leaving and loss. Their journey to the interior then brings them into an ever-unfolding landscape of moments that hover between past and present.

The last night of the third moon, an inn at the foot of Mount Nikko. The innkeeper is called Hotoke Gozaemon,

“Joe Buddha.” He says his honesty earned him the name and invites me to make myself at home. A merciful Buddha suddenly appearing like an ordinary man to help a pilgrim along his way, his simplicity’s a great gift, his sincerity unaffected. A model of Confucian rectitude, my host is a bodhisattva.

Here, we and our companions find that the usual distinctions—between high and low, sacred and secular, who is to be revered and who is to be disdained—are melting away. And thus, through such humble and direct encounters in the next 45 sections, the two old travelers explore what the living world still gives them.

Sora, suffering from persistent stomach ailments, was forced to return to his relatives in Nagashima in Ise Province. His parting words:

Sick to the bone

if I should fall, I’ll lie

in fields of cloverHe carries his pain as he goes, leaving me empty. Like paired geese parting in the clouds.

Now falling autumn dew

obliterates my hatband’s

“We are two”

Hamill comments that the travelers had inscribed their hatbands to indicate that they were traveling “with the Buddha.” The final line—“We are two”—points at a depth of separation, both inward and outward, that was not expected. Here a sustaining friendship falls away as a deeper sense of hollowness, a deeper solitude, unfolds.

In the poems that follow, Basho is bereft of his friend’s companionship, and his compositions are focused more on natural landscapes and the act of writing about them. Images and occurrences have a great sharpness and clarity in the desolation where they hover.

On the fifteenth, just as the innkeeper predicted, it rained:

A harvest moon, but

true North Country weather—

nothing to view. . .

Loneliness greater

than Genji’s Suma Beach:

the shores of autumn

When he returns home, as he describes in the following and final poem of the narrative, Basho is welcomed by friends. Sora too, recovered from his illness, is there to greet him. And yet, as all of us must face our end alone, Basho enters a time that is more solitary than ever.

Still exhausted and weakened from my long journey, on the sixth day of the darkest month, I felt moved to visit Ise Shrine, where a twenty-one-year Rededication Ceremony was about to get underway. At the beach, in the boat, I wrote:

Clam ripped from its shell

I move on to Futami Bay:

passing autumn

How shall we receive this poem? Basho found his return to customary social life almost excruciating, as if the sensitivity and receptiveness that had opened during his solitary wandering had peeled something back, left something bare—something that was now being scratched, bruised, exposed to harsh winds. He made an excuse that allowed him to wander once again. But now he would also leave autumn behind. Only the icy stillness and life-end of snow and winter remained, as he sought a solitude transcending time, space, and separation.

Now, in Narrow Road to the Interior, Basho continues to offer us aged wanderers companionship on this journey.

Now I imagine I am sharing this reading and my passing observations with two friends whom I recently saw. One had suddenly gone blind, the other had suffered strokes, broken bones, the death of an only son. They lived, as they had all their lives, on farms quite far apart. But now their longstanding close friendship was hard to access, even as their courage, love, and integrity remain. I don’t know whether this reading would interest them very much. If not, I can imagine that they would, so kindly, change the subject.