As days lengthen and the long winter draws to a close, agricultural villages across western Himalaya start to bustle with activity. Farmers prepare their fields for the upcoming growing season, and blooming apricot flowers splash hues of pink across the barren landscape. April brings the first signs of spring, and with it, the time for saka, or first plow, has arrived.

The first plow is a particularly special occasion for agricultural villages in India’s northern region of Ladakh, and Buddhist rituals frequently supplement agrarian traditions to bless the land, protect the village, and usher in a fruitful season. Some villages consult local astrologers to determine the date of the first plow, while in other villages, the heads of house congregate to decide. Saka traditions vary from village to village to accommodate distinct needs and environments. This year, I traveled to two Ladakhi villages, Tar and Basgo, to learn about their plowing rituals and the relationships between Buddhist practice and the environment.

Tucked between narrow mountain gorges, Tar is one of the few remaining Ladakhi villages accessible only by foot. Basgo, on the other hand, is a large village that stretches roughly seven kilometers along the Leh-Manali Highway and extends in both directions from that highway—up the valley and down to the Indus River. Plowing traditions in these villages simultaneously connect them to their distinctive histories and provide a glimpse into the trajectory of Ladakh’s future.

On the first day of plow in Tar, soft echoes of conversation mix with the words being read from the sacred Buddhist text Byang chub sems kyi bstod pa rin chen sgron ma (Precious Lamp of Praise of the Bodhicitta). Nearby, men affix the wooden yoke and plow to the shoulders of two dzos—a hybrid between a yak and a cow. This year, Urgyan, a high school student from Tar who now studies near Leh, has returned home to assist his mother and paternal grandfather in plowing their fields. Urgyan’s maternal grandfather, Tsering, has also made the journey to Tar to help his daughter.

With Tar’s dwindling and rapidly aging population, Urgyan and Tsering’s participation is greatly appreciated. Several villagers, as well as an American couple who has lived intermittently in Tar since 2015, join the family in this year’s plow. Long-held systems of interfamilial reciprocity instilled by ancestors have ensured that no family has to tend to their fields single-handedly. For generations, this group of households in Tar has helped one another not only plow each other’s fields but also offered aid in times of need, grief, and celebration. Everyone’s fields will be plowed in turn, but today—the first day—the group plows the fields belonging to Achey Tashi, Urgyan’s mother.

Before the plow breaks through the soil, Tsering awakens the earth spirits who might have settled in the soil during Tar’s long winter. He informs them of the intrusive plowing activities soon to commence and requests that they vacate the field to avoid injury from the plow. Proceeding without awaking and mollifying these spirits risks failure, or even catastrophe. Inside Achey Tashi’s home, the rest of the group sips warm cups of butter tea and finishes their breakfast.

As breakfast concludes, the men of the household gather materials harvested from the earth—juniper (shukpa), incense, barley flour (phey), water, barley beer (chang), flowers, and butter (yar)—to give as offerings. They recite Buddhist prayers while the eldest begins to read the Buddhist text and the youngest throws a modest handful of barley flour up into the air. Achey Tashi brings everyone a chapati, Ladakhi flatbread, to take to the field. With prayers said, earth spirits awakened, and chapati in hand, it is time to start plowing the fields.

On the edge of the field, one man sits alongside a smoldering incense burner and an offering of barley beer, completing the recitation of the Buddhist text to bless the land and all living beings. The eldest man of the household, Urgyan’s paternal grandfather, walks through the field scattering the barley seeds that will be churned into the soil. Meanwhile, several men polish the dzos’ horns with butter and secure the twelve-part wooden yoke and plow to their shoulders. Once they’re readied, Tsering guides the dzos rhythmically across the field, singing traditional Ladakhi songs praising the dzos’ strength. His grandson, Urgyan, steers the plow through the soil. Following behind them, several villagers break upturned masses of earth and smooth the newly carved grooves. Throughout the day, Achey Tashi keeps everyone well-fed with frequent tea and barley beer breaks.

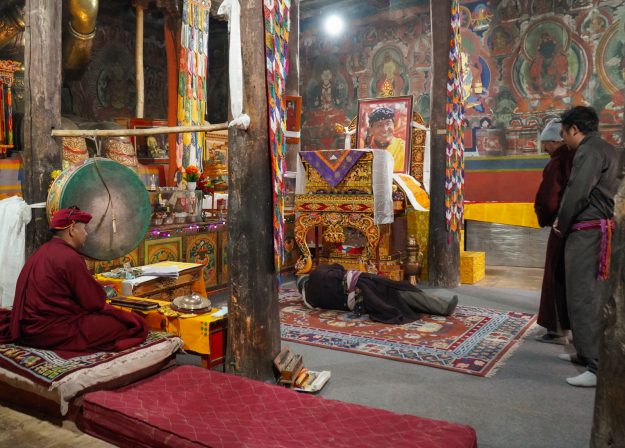

In Basgo, saka is more ceremonial than functional and begins high above the fields in the Buddhist temples that tower atop Basgo’s anomalous melting mountain landscape. Inside the temples, extraordinary 16th-century murals fill the walls, and a colossal sculpture of Maitreya (the future Buddha) sits at the apex. Here, surrounded by pictorial Buddhist pantheons and allusions to Basgo’s royal past, a few villagers and a monk gather to begin the saka rituals.

In the days leading up to saka, the village onpo (astrologer) determines the auspicious date, and several men circulate through the village to collect barley seeds from each home. These seeds symbolize the inclusion of every home in the first plow. In previous generations, many villagers participated in saka rituals, but today, with younger generations abandoning village life, only a handful of villagers maintain the traditions.

Once the date has been fixed and barley seeds collected, the men gather in the monastery, where a monk reads from a Buddhist text to bless the seeds, the environment, and all sentient beings dwelling in it. While the monk recites sacred words, the man holding the satchel of barley (pispa) rolls on the floor speechless, playing the character of a mute fool. He remains speechless until they all reach the fields, where he will follow behind the plow and scatter the barley seeds.

When the monk finishes his prayers, the men go up the valley to the field owned by the monastery. Beside the field, the monk continues to read the Buddhist text. His words stream through the entire ceremony, providing the sonorous backdrop for the saka ritual. Similar to Tar, someone must first awaken the earth spirits and inform them of the imminent plow. Others prepare the animals and bring out the earthen offerings of barley flour, barley beer, incense, and butter to give to the dzos, the land, its inhabitants, and those performing the rituals. Once the earth spirits have roused, offerings have been given, and the dzos readied, the men set forth to pull the plow through the field. Compared with Tar’s full-day endeavor, Basgo’s plow is relatively brief and consists of tilling only one field. After saka, the water channels are opened, and villagers can begin plowing their fields according to their own timelines.

Over the years, due to the relentless pace of modernization and cultural change sweeping across Ladakh, fewer and fewer families actively maintain traditional agricultural practices such as saka. And as each generation’s reliance and knowledge on the land diminishes, so, too, does the memory and significance of these traditions and their accompanying rituals. These plowing traditions and Buddhist rituals don’t just demonstrate the intimate and sustainable relationships forged between Ladakhi communities and their environments. They also demonstrate how Buddhism exists beyond texts and temples, and serve as a thread to connect Ladakhis with their history.

Reflecting back on this year’s plow, Urgyan told me, “It’s not only about the work. I would say it’s a kind of celebration. Everyone works together as a team but gets sufficient rest, with lots of tea and local beer. Elders crack good jokes and share old stories about how things used to be.”

As dusk settled in Tar, we looked proudly at the freshly plowed fields and newly tilled earth. Soon, green shoots will break through the soil and remind us of the unstoppable passage of time.