When I first encountered Zen in the 1960s, I found myself particularly drawn to the mysterious satori—that moment of seeing into one’s own true nature, when all the old blinders were said to fall away. In such a moment, I imagined, one became an entirely new person, never to be the same again. I found the prospect of this kind of ultimate realization compelling enough to turn my life in that direction.

Yet along the way I also discovered something I was not prepared for: that spiritual realization is relatively easy compared with the much greater difficulty of actualizing it, integrating it fully into the fabric of one’s daily life. Realization is the movement from personality to being, the direct recognition of one’s ultimate nature, leading toward liberation from the conditioned self, while actualization refers to how we integrate that realization in all the situations of our life. When people have major spiritual openings, often during periods of intensive practice or retreat, they may imagine that everything has changed and that they will never be the same again. Indeed, spiritual work can open people up profoundly and help them live free of the compulsions of their conditioning for long stretches of time. But at some point after the retreat ends, when they encounter circumstances that trigger their emotional reactivity or their habitual tensions and defenses, they may find that their spiritual practice has hardly penetrated their conditioned personality, which remains mostly intact, generating the same tendencies it always has.

Of course, realization has many levels, from temporary experiences to more stable attainment. Yet even among advanced spiritual practitioners, certain islands—unexamined complexes of personal and cultural conditioning, blind spots, or areas of self-deception—may often remain intact within the pure stream of their realization. Some would say that these shadow elements are signs of deficiency in one’s spiritual practice or realization, and this is undoubtedly true. Yet since they are so common, they also point to the general difficulty of integrating spiritual awakenings into the entire fabric of our human embodiment.

In the traditional cultures of Asia, it was a viable option for a yogi to pursue spiritual development apart from worldly involvement, or to live purely as the impersonal universal, without having much of a personal life or transforming the structures of that life. These older cultures provided a religious context that honored and supported spiritual retreat and placed little or no emphasis on individual concerns. In Asia, yogis and sadhus who had little personal contact with people could still be venerated by the community at large.

Many Westerners have tried to take up this model, pursuing impersonal realization while neglecting their personal life, but have found in the end that this was like wearing a suit of clothes that didn’t quite fit. Taking on the challenges of a fully engaged personal life—finding right livelihood in a complex materialistic world, being involved in a committed intimate relationship, dealing with the social and political concerns facing us at every turn—inevitably brings up unresolved psychological issues. For this reason, Western seekers may also need the help of psychological methods to help them more fully integrate spiritual practice and realization into their lives.

For most of my career I have explored what the Eastern contemplative traditions have to offer Western psychology. Yet more recently I have also become interested in a different question: How might Western psychological work serve a sacred purpose, by helping us to integrate our spiritual insights into our everyday lives? In its ability to shine light into the hidden nooks and crannies of our conditioning, psychological inquiry can serve as a powerful ally to spiritual practice. It can help break up the hard, rocky soil of our personality patterns so that this soil becomes permeable, allowing the seeds of spiritual realization to take root and blossom there more fully. Of course, this kind of psychological work would require a much larger understanding and aim than conventional psychotherapy, whose focus is on pathology and cure rather than transformation.

Psychological and spiritual work address different levels of human existence. If the domain of spiritual work is emptiness—unconditioned, universal, absolute truth—the domain of psychological work is form—our individual, conditioned ways of experiencing ourselves and the world—or relative truth. Spiritual practice, especially mysticism, points toward a timeless trans-human reality, while psychological work addresses the evolving human realm, with all its issues of personal meaning and interpersonal relationship.

My initial interest in psychotherapy developed in the 1960s, at the same time as my interest in the Eastern spiritual traditions. At first I imagined that psychotherapy could be the Western version of a path of liberation. But I quickly found Western psychology too narrow and limited in its view of human nature. As I became more involved in Buddhism, I went through a period of aversion to Western psychology. Now that I had “found the way,” I became arrogant regarding other paths, as new converts often do. I was also wary of becoming trapped in endlessly processing emotional issues. But in my newfound spiritual fervor, I was falling into the opposite trap—of refusing to face the personal “stuff” at all. In truth, I was much more comfortable with the impersonal, timeless reality I discovered through Buddhism than with my personal life. Compared with the peace and clarity of sitting still and following the breath while resting in the open space of awareness, my personal feelings seemed messy and entangling.

Yet in studying Tantric Buddhism, with its respect for relative truth, I began to appreciate aspects of Western psychology in a new light. Once I accepted that psychology could not describe my ultimate nature, and I no longer required it to provide answers about the nature of human existence, I realized that it had an important place in the scheme of things. I also found that my own personal psychological work helped me approach spiritual practice less encumbered by unconscious agendas.

It can be difficult to understand or appreciate why we might need to resort to psychological work when many Asian spiritual practitioners have found liberation solely through the profound teachings and practices of Buddhism for thousands of years. But it helps to recognize that the highest, nondual Buddhist teachings, which show that who you really are is absolute reality, presume a rich underpinning of community, religious customs, and shared moral values that the West mostly lacks. Modern Western culture is marked by social isolation, personal alienation, lack of community, disconnection from nature, and the loss of the sacred at the center of our lives. And the Western self is riddled with inner divisions—between self and other, individual and society, mind and body, spirit and nature, or the guilty ego and the harsh, punishing superego—that were mostly unknown in the ancient cultures in which the meditative traditions first arose.

Many Western children also grow up lacking close, sustained early bonding with their parents, in contrast to the practice in traditional cultures, where parents often hold young children continually and even let them share their bed. Developmental psychologists argue that children with deficient parenting tend to hold onto the internalized traces of their parents more rigidly and develop parental fixations that haunt them in later life.

Thus Western children often grow up without the support of what the psychologist D. W. Winnicott called a good “holding environment”—a context of love and belonging that contributes to a basic sense of confidence and to overall healthy psychological development. Children who grow up in fragmented families, glued to television sets transmitting images of a spiritually lost, narcissistic world, lack a meaningful context in which to situate their lives. As a result, many Westerners suffer from what the psychologist Harry Guntrip considered to be the emotional plague of modern civilization: ego weakness, the lack of a grounded sense of oneself and one’s place in the world that shows up as self-hatred, insecurity, and self-doubt.

Because their ego structure serves as a defense against inner fragmentation, many Western seekers find that they are not willing or able to let go of their ego defenses, despite all their spiritual practice and realization. On a deep, subconscious level, it is too threatening to let go of the little security that their shaky ego structures provide. This is why it can be helpful for Westerners to work on dismantling the defensive personality structure in a more gradual and deliberate way, through psychological inquiry—examining and dissolving false self-images, distorted projections, and habitual emotional reactions—and developing a fuller connection with themselves in the process. In this way, psychological work can serve another important function for Westerners: helping them to individuate by clearing up the emotional conflicts that prevent them from finding an inner core of authenticity.

If the great gift of the East is its focus on absolute true nature—impersonal and shared by all alike—the gift of the West is the impetus it provides to develop an individuated expression of true nature—which we can also call soul, or personal presence. For traditional Asians, soul (defined as the rich, colorful qualities of our humanness) was thoroughly woven into the warp and woof of their culture. But in a materialistic culture that has lost its soul, it becomes more important for people to individuate—to cultivate individual soul qualities and find an authentic inner source of personal meaning and purpose not found in the society at large.

Coming out of traditional Asian societies, many Eastern spiritual teachers have a hard time recognizing the developmental challenges facing their Western students and may not understand their pervasive self-hatred, shame, and guilt, as well as their alienation and lack of confidence. These teachers may also fail to detect their students’ tendency to engage in “spiritual bypassing”—a term I coined to describe the use of spiritual ideas and practices to shore up a shaky sense of self, or to belittle basic needs, feelings, and developmental tasks in the name of enlightenment. And so they often teach self-transcendence to students who first of all need to find some ground to stand on.

When people use spiritual practice to try to compensate for feelings of alienation and low self-esteem, they corrupt the true nature of spiritual practice. Instead of loosening the manipulative ego that tries to control its experience, they strengthen it, and their spiritual practice remains unintegrated with the rest of their life.

Using spirituality to make up for failures of individuation—psychologically separating from parents, cultivating self-respect, or trusting one’s own intelligence as a source of guidance—also leads to many of the so-called “perils of the path”: spiritual materialism (using spirituality to prop up a shaky ego), self-inflation, “us vs. them” mentality, groupthink, blind faith in charismatic teachers, and loss of discrimination. Spiritual communities can become a kind of surrogate family, where the teacher is regarded as the good parent while the students are striving to be good boys or good girls—trying to please the teacher-as-parent or driving themselves to climb the ladder of spiritual success. In this way, spiritual practice becomes co-opted by unconscious identities and used to reinforce unconscious defenses.

For example, people resorting to isolation and withdrawal because the interpersonal realm feels threatening often use teachings about detachment and renunciation to rationalize their aloofness, impersonality, and disengagement when what they really need is to become more fully embodied, more engaged with themselves, with others, and with life. People with a dependent personality structure, who try to gain approval and security by pleasing others, often perform unstinting service for the teacher or community in order to feel worthwhile. They confuse a co-dependent kind of self-negation with true selflessness. And spiritual involvement is particularly tricky for people who hide behind a narcissistic defense, because they use spirituality to make themselves feel special or important while imagining they are working on liberation from self.

Spiritual bypassing often adopts a rationale using absolute truth to deny or disparage relative truth. Absolute truth is what is eternally true, now and forever, beyond any particular viewpoint or time frame. When we tap into absolute truth, we can recognize the divine beauty or larger perfection operating in the whole of reality. From this larger perspective, the murders on tonight’s news, for instance, do not diminish this divine perfection, for the absolute encompasses the whole panorama of life and death, in which suns, galaxies, and planets are continually being born and dying. However, from a relative point of view—if you are the wife of a man murdered tonight—you will probably not be moved by the truth of ultimate perfection. Instead you will be feeling human grief.

There are two ways of confusing absolute and relative truth. If you use the murder or your grief to deny or insult the higher law of the universe, you would be committing the relativist error. You would be trying to apply what is true on the horizontal plane of becoming to the vertical dimension of pure being. The spiritual bypasser makes the reverse category error, the absolutist error: He draws on absolute truth to disparage relative truth. His logic might lead to a conclusion like this: Since everything is ultimately perfect in the larger cosmic play, grieving the loss of someone you love is a sign of spiritual weakness.

Since it is the nature of human beings to live on both the absolute and relative levels, we can never reduce reality to a single dimension. We are not just this relative body-mind organism; we are also absolute being/awareness/presence, which is much larger than our bodily form or personal history. But we are also not just this larger, formless absolute; we are also incarnate as particular individuals. If we identify only with form, our life will remain confined to known, familiar structures. But if we try to live only as pure emptiness, or absolute being, we may not engage with our humanity. In absolute terms, the personal self is not ultimately real; at the relative level, it must be respected.

A client of mine who was desperate about her marriage had gone to a spiritual teacher for advice. He advised her not to be so angry with her husband but to be a compassionate friend instead. This was certainly sound spiritual advice. Compassion is a higher truth than anger; when we rest in the absolute nature of mind, pure open awareness, we discover compassion as the very core of our nature. From that perspective, feeling angry about being hurt only separates us from our true nature.

Yet the teacher who gave this woman this advice did not consider her relative situation—that she was someone who had swallowed her anger all her life. Her father had been abusive and would slap her and send her to her room whenever she showed any anger about the way he treated her. She learned to suppress her rage and always tried to please others by being “a good girl” instead. So when the teacher advised her to feel compassion rather than anger, she felt relieved because this fit right in with her defenses. Since anger was threatening to her, she used the teaching on compassion for spiritual bypassing—for refusing to deal with her anger or the message it contained.

As her therapist, I had to take account of her relative situation and help her relate to her anger more fully. As a spiritual practitioner, I was also mindful that anger is ultimately empty, a wave arising in the ocean of consciousness, without any solidity or inherent meaning. Yet while that understanding may be true in the absolute sense, and generally valuable for helping dissolve attachment to anger, it was not useful for this woman at this time. Instead, she needed to learn to pay more attention to her anger in order to move beyond a habitual pattern of self-suppression, to connect with her inner strength and power, and to relate to her husband in a more active, assertive way.

How then do we arrive at genuine compassion? Spiritual bypassing involves imposing on oneself higher truths that lie far beyond one’s immediate existential condition. My client’s attempts at compassion were not entirely genuine because they were based on denying her own anger. Spiritual teachers often exhort us to be loving and compassionate, or to give up selfishness and aggression, but how can we do this if our habitual tendencies arise out of a whole system of psychological dynamics that we have never clearly seen or faced, much less worked with? People often have to acknowledge and come to terms with their anger before they can arrive at genuine forgiveness or compassion. That is relative truth.

Psychological inquiry starts here, with relative truth, with whatever we are experiencing right now. It involves opening to that experience and exploring its meaning, letting it unfold without judgment. As a therapist, I find that allowing whatever arises to be there as it is and gently inquiring into it leads naturally in the direction of deeper truth. This is what I call psychological work in the service of spiritual development.

Many people who seek out my services have done spiritual practice for many years. I have often been struck by the huge gap between the sophistication of their spiritual practice and the level of their personal development. Some of them have spent years doing what were once considered the most advanced, esoteric practices, reserved only for the select few in traditional Asia, without developing the most rudimentary forms of self-love or interpersonal sensitivity. One woman who had undergone the rigors of a Tibetan-style three-year retreat had little ability to love herself. The rigorous training she had been through only seemed to reinforce an inner discontent that drove her to pursue high spiritual ideals without showing any kindness toward herself or her own limitations.

In addition to spiritual bypassing, another major problem for Western seekers is their susceptibility to the “spiritual superego,” a harsh inner voice that acts as relentless critic and judge telling them that nothing they do is ever quite good enough: “You should meditate more and practice harder. You’re too self-centered. You don’t have enough devotion.” This critical voice keeps track of every failure to practice or live up to the teachings, so that practice becomes more oriented toward propitiating a judgmental part of themselves than opening to life unconditionally. They may subtly regard the saints and enlightened ones as father figures who are keeping a critical eye on all the ways they are failing to live up to their commitments. So they strive to be “Dharmically correct,” attempting to be more detached, compassionate, or devoted than they really are, while secretly hating themselves for failing to do so, thus rendering their spirituality cold and solemn. Their self-hatred was not created by the spiritual teaching; it already existed. But by pursuing spirituality in a way that widens the gap between how they are and how they think they should be, they wind up turning exquisite spiritual teachings on compassion and awakening into fuel for self-hatred and inner bondage.

This raises the question of how much we can benefit from a spiritual teaching as a set of ideals, no matter how noble those ideals are. Often the striving after a spiritual ideal only serves to reinforce the critical superego—that inner voice that tells us we are never good enough, never honest enough, never loving enough. In a culture permeated by guilt and ambition, where people are desperately trying to rise above their shaky earthly foundation, the spiritual superego exerts a pervasive unconscious influence that calls for special attention and work. This requires an understanding of psychological dynamics that traditional spiritual teachings and teachers often lack.

Paul, a therapy client of mine, had been a dedicated Buddhist practitioner for more than two decades. A husband, father, and successful businessman, he had recently been promoted to a position that involved public speaking. After a few experiences in front of large audiences, he started feeling overwhelmed by anxiety, worry, tension, and sleeplessness. At first, he tried to deal with his distress by meditating more. While this would help him regain some equilibrium, the same symptoms would recur when he next faced an audience. After a few months of this, he gave me a call.

From the Buddhist teachings, Paul knew the importance of not being attached to praise and blame, two of the eight worldly concerns, along with loss and gain, pleasure and pain, success and failure, that keep us chained to the wheel of suffering. Yet it was not until his fear of public speaking brought up intense anxiety about praise and blame that he realized just how concerned he was about how people saw him.

As our work progressed, he realized that he used detachment as a defense, to deny an underlying fear about how other people saw him. He had developed this defense to cope with not feeling seen by his parents. His mother had lived in a state of permanent tension and anxiety. Regarding him as her potential savior rather than a separate being with feelings apart from her, she led him to feel responsible for her happiness. To shield himself from her intrusiveness, Paul had adopted a defensive stance of not feeling his need for her, and by extension, for other people. Having tried all his life not to care about how people regarded him, he was particularly attracted to the Buddhist teachings of no-self when he first encountered them. After all, in the light of absolute truth there is nobody to be seen, nobody to be praised, nobody to be blamed, and Paul found great comfort in this. Yet on the relative level, Paul carried within him a frustrated need to be seen and loved. In denying this need through “spiritual work,” Paul was practicing defensiveness, not true nonattachment.

Paul was doubly trapped. As long as he could not acknowledge the part of him that felt, “Yes, I want to be seen and appreciated,” his frustrated need for love kept him tied in knots, secretly on the lookout for others’ praise and confirmation. And his inability to say, “No, I do not exist to make you happy,” kept him susceptible to potential blame whenever he failed to please others.

Yes and no are expressions of desire and aggression—two life energies that philosophers, saints, and psychologists, from Plato and Buddha to Freud, have considered particularly problematic. Unfortunately, many spiritual teachers simply criticize passion and aggression instead of teaching people to unlock the potential intelligence hidden within them.

The intelligent impulse contained in the yes of desire is the longing to expand, to connect more fully with life. The intelligence contained in no is the capacity to discriminate, differentiate, and protect oneself and others from harmful forces. The energy of the genuine, powerful no can be a doorway to strength and power, allowing us to separate from aspects of our conditioning we need to outgrow. Our capacity to express the basic power of yes and no often becomes damaged in childhood. And this incapacity becomes installed in our psychological makeup as a tendency to oscillate between compliance and defiance, as Paul exemplified in his attitude toward others, secretly feeling compelled to please them, yet secretly hating them for this at the same time.

As long as Paul failed to address his unconscious dynamic of compliance and defiance, his spiritual practice could not help him stabilize genuine equanimity, free from anxiety about praise and blame. Although he could often experience equanimity during periods of solitary spiritual practice, these realizations remained compartmentalized and failed to carry over into his interpersonal relationships.

Before Paul could find and express his genuine yes—to himself, to others, to life—he had to say no to the internalized mother whose influence remained alive within him: “No, I don’t exist to make you happy, to be your savior, to give your life meaning.” But it was not easy for him to acknowledge his anger toward his mother for making him the object of her narcissistic needs. Quoting spiritual doctrine, Paul believed it was wrong to hate. Yet in never letting himself feel the hatred he held in his body, he wound up expressing it in covert, self-sabotaging ways. I did not try to push past his inner taboo against this feeling but only invited him to acknowledge his hatred when it was apparent in his speech or demeanor. When Paul could finally let himself feel his hatred directly, instead of judging or denying it, he came alive in a whole new way. He sat up straight and broke into laughter, the laughter of an awakening vitality and power.

A second defining moment came when Paul finally acknowledged his need to be loved for who he was, which triggered a surge of energy that filled his whole body. Yet this was also scary, for it felt as though he were becoming inflated. And for Paul, with his refined Buddhist sensibilities, self-inflation was the greatest sin of all—a symptom of a bloated ego, the way of the narcissist who is full of himself.

Seeing his resistance, I encouraged him to explore, if only for a few moments, what it would be like to let himself become inflated, to feel full of himself, and to stay present with that experience. As he let himself fill up, he experienced himself as large, rich, and radiant. He felt like a sun king, receiving energy from the gods above and below, radiating light in all directions. He realized that he had always wanted to feel this way, but had never allowed himself to expand like this before! Yet now he was letting himself be infused by the fullness that had been missing in his life—the fullness of his own being. To his surprise, he found it a tremendous relief and release to allow this expansion at last.

As Paul got over his surprise, he laughed and said: “Who would have thought that letting myself become inflated could be so liberating?” Of course, he wasn’t acting out a state of ego inflation, but rather feeling what it was like to let the energy of desire, fullness, and spontaneous self-valuing flow through his body. In this moment of according himself the recognition he had secretly sought from others, he did not care about how others saw him. Nor was there any desire to lord his newfound strength over anyone.

Many spiritual seekers who suffer, like Paul, from a deflated sense of self, take spiritual teachings about selflessness to mean that they should keep a lid on themselves and not let themselves shine. Yet instead of overzealously guarding against ego inflation, Paul needed to let his genie out of the bottle before he could distinguish between genuine expressions of being such as power, joy, or celebration, and ego distortions like grandiosity and conceit.

As typically happens in many spiritual communities, Paul had used spiritual practice as a way of trying to deny certain basic human needs. Yet trying to leap directly from rejecting his need for love to a state of needlessness was only spiritual bypassing—using spiritual teachings to reinforce a subconscious defense. When he could finally acknowledge his need, he found that it contained within it a genuine, powerful yes to life and love that diminished his fixation on outer praise and blame.

Although Paul’s spiritual practice had helped loosen his identification with a fixed self-concept—what I call the conscious identity—it had not helped him fully address his lingering sense of inadequacy and unworthiness stemming from childhood—an even more problematic subconscious identity. It is often hard to dislodge or transform this kind of subconscious identity, which has its roots in interpersonal dynamics, through meditation practice alone, which is mostly a solitary activity. Our work together, with its relational focus, brought Paul’s underground sense of deficiency to light so that he could work with it directly. This also had a clarifying effect on his spiritual practice, helping him make an important distinction between absolute emptiness—the ultimate reality beyond self—and relative, psychological emptiness—his sense of being lacking or deficient. Because he had previously conflated these two types of emptiness, his spiritual practice had in some ways served to reinforce his old sense of inadequacy.

Paul’s psychological conflicts also cut off his access to deeper capacities such as strength, confidence, and the ability to connect with others in a genuinely open way. These intrinsic human capacities—traditionally described as “the qualities of a Buddha”—can be seen as differentiated expressions of true nature. If realizing pure, undifferentiated being is the path of liberation, then embodying a full spectrum of these differentiated qualities of being is the path of individuation in its deepest sense: the unfolding of our deepest human resources and imperatives, which exist as seed potentials within us, but which are often blocked by psychological conflicts.

This understanding of individuation goes far beyond the secular, humanistic ideal of developing one’s uniqueness, being an innovator, or living out one’s dreams. Instead, it involves forging a vessel—our capacity for personal presence, nourished by its rootedness in deeper human qualities—through which we can bring absolute true nature into form—the “form” of our person.

By person I do not mean some fixed structure or entity, but the way in which true nature can manifest and express itself in a uniquely personal way, as the ineffable suchness or “youness” of you. Since individuation involves clarifying the psychological dynamics that obscure our capacity to shine through, it is not opposed to spiritual realization. Instead, it involves becoming a more transparent vessel—an authentic person who can bring through what is beyond the person in a uniquely personal way.

Working in this way to clear up old emotional conflicts can help us develop a richer quality of personal presence and begin to embody our true nature in an individuated way. Our individuated nature can then become a window opening onto all that is beyond and greater than ourselves.

While spiritual traditions generally explain the cause of suffering in general terms as the result of ignorance, faulty perception, or disconnection from our true nature, Western psychology provides a more specific developmental understanding. It shows how suffering stems from childhood conditioning; in particular, from static and distorted images of self and other that we carry with us in the baggage of our past. And it reveals these painful, distorting identities as relational—formed in and through our relationships with others.

Spiritual traditions that do not recognize the way in which ego identity forms out of interpersonal relationships are unable to address these interpersonal structures directly. Instead, they offer practices—prayer, meditation, mantra, service, devotion to God or guru—that shift the attention to the universal ground of being in which the individual psyche moves, like a wave on the ocean. Thus it becomes possible to enter luminous states of trans-personal awakening, beyond personal conflicts and limitations, without having to address or work through specific psychological issues and conflicts. This kind of realization can certainly provide access to greater wisdom and compassion, but it often does not touch or alter impaired ego structures which, because they influence our everyday functioning, prevent us from fully integrating this realization into the fabric of our lives. Thus, as Sri Aurobindo put it, “Realization by itself does not necessarily transform the being as a whole. One may have some light of realization at the spiritual summit of consciousness but the parts below remain what they were.”

We in the West have been exposed to the most profound nondual teachings and practices of the East for only a few short decades. Now a deeper level of dialogue between East and West is called for in order to develop greater understanding about the relationship between the impersonal absolute and the human, personal dimension. Indeed, expressing absolute true nature in a thoroughly personal, human form may be one of the most important evolutionary potentials of the cross-fertilization of Eastern contemplative traditions and Western psychological understanding. Bringing these two approaches into deeper dialogue may help us discover how to transform our personality in a more complete way—developing it into an instrument of higher purposes—thus redeeming the whole personal realm, instead of just seeking liberation from it.

Buddhism has always grown through incorporating methods and understandings indigenous to the cultures to which it spread. If psychotherapy is our modern way of dealing with the psyche and its demons (analogous to the early Tibetan shamanic practices that Vajrayana Buddhism integrated into its larger framework), then the meditative traditions may find a firmer footing in our culture through relating to Western psychology more fully.

For psychological and spiritual work to be mutually supportive allies in the liberation and embodiment of the human spirit, we need to re-envision both paths for our time, so that psychological work can serve spiritual development, while spiritual work can take into account psychological development. These two traditions would then come together as convergent streams, furthering humanity’s evolution toward realizing its true nature—as belonging to the universal mystery that surrounds and inhabits all things—and embodying this larger nature as human presence in the world, thus serving as a crucial link between heaven and earth.

♦

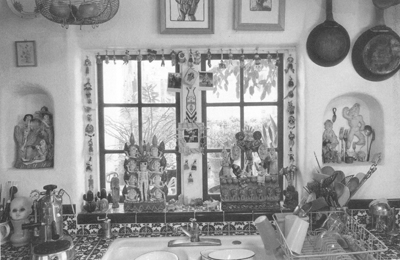

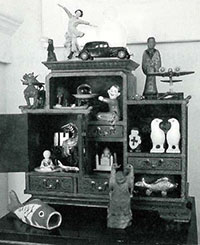

This article has been specially condensed and adapted for Tricycle from John Welwood’s book, Toward A Psychology of Awakening: Buddhism, Psychotherapy, and the Path of Personal and Spiritual Transformation, published by Shambhala Publications. Copyright © John Welwood. Photographs by Jean McMann, from her book Altars and Icons: Sacred Spaces in Everyday Life (Chronicle, 1998).