We came to Nepal as pilgrims. From the US, Canada, and Hong Kong, we came to dance and sing in the power places of the Kathmandu Valley—also known as the Nepal Mandala. A mandala is an archetypal blueprint of a pure land, or sacred realm of a deity. This fertile valley at the foot of the great Himalayan range has been coined by Buddhist scholar Keith Dowman as “the playground of the Himalayan gods” due to countless myths of divine beings taking place at its many sites. Thus, the Nepal Mandala is considered to be a major power place graced by divine presence and visited by many Buddhist sages, yogis, and pilgrims throughout the ages. We came to connect with the energy of this place, to revitalize it with our own joyful devotion, and to spark an interior journey. What that inner journey would be, I could not predict.

We were a group of practitioners of Charya Nritya, the Newar Vajrayana practice, more than a thousand years old, of singing and dancing as a spiritual discipline. (Newar refers to the indigenous people and culture of the Kathmandu Valley in Nepal.) Our teacher is Prajwal Ratna Vajracharya, a 35th-generation Newar Vajrayana priest. Prajwal (as we call him) was born and raised within the nonmonastic, priestly Vajracharya caste in Kathmandu, at a time when knowledge of the Charya Nritya traditions was waning. This decline was due to the secrecy of the practices, political challenges of existing in a Hindu-majority country, and modernization. At an early age, Prajwal was instructed by his father, the renowned priest and scholar Ratna Kaji Vajracharya, to take their teachings out into the world and make them public. In fulfillment of that charge, Prajwal now lives and teaches at the Nritya Mandala Mahavihara in Portland, Oregon, which he cofounded in 2009.

As world travel started to reopen after COVID-19 lockdowns, Prajwal decided it was time to return to his homeland and demonstrate to the local community how their traditions have been embraced and taken root in the West. We would be invigorating our own practice by connecting with the people, geography, rituals, art, and architecture that formed and framed the traditions we had learned from him.

The Kathmandu Valley is a fifteen-mile-long, elliptical-shaped mandala protected by the great Himalayan range to the north and tropical jungles to the south. Within this protected valley, Newar Buddhism, with its highly ritualistic blend of Himalayan and Indian cultural elements and Sanskrit liturgies, has remained intact since medieval times. It offers a uniquely sensorial experience of the dharma through physical practices, from creating individual pictorial mandalas during rituals to sacred dancing during deity meditation.

Deep reverence for and worship of the divine feminine as the mother-goddess, or devi, pervades both the Buddhist and Hindu religious views in this mandala. Even the exquisitely carved wooden roof-struts on Newar temples and many secular buildings pay visual homage to the endless array of goddesses wielding their innumerable gifts and weapons. In fact, the goddesses (as struts) literally emerge from the building exteriors to hold up the roof!

In Newar Buddhism, the sacred feminine frequently takes the form of Vajrayogini. Her name means “Adamantine Yogini,” and she manifests a pure and utterly blissful state of indestructible enlightenment. Her naked, red, dancing body marks her as a dynamic and joyful agent of transformation. As the supreme female Buddha of the tantric pantheon, she appears in multiple emanations, and the valley is saturated with her presence and energy. She is the central focus for much esoteric meditation and ritual—though on a mundane level, she is worshiped as a source of beneficence and blessing. Her presence is so pervasive that the sacred places devoted to her worship form their own mandala—a yogini mandala—within the greater Nepal Mandala.

Four yogini temples make up this yogini mandala: Pharping Vajrayogini Temple, Sankhu Khadga Yogini Temple, Pashupatinath Guhyeshwari Temple, and Bijeshwori Temple. Each temple honors a different form of the deity.

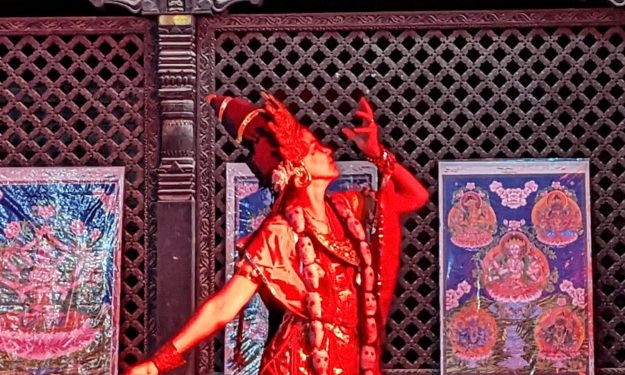

In Buddhist iconography, each of Vajrayogini’s forms is rendered naked, wearing only jewel and bone ornaments that sway and ripple as she moves. Her red color radiates energetic, creative power. Her left hand holds a drinking vessel made from a human skull from which she drinks blood, which she transforms into ambrosia. Meanwhile, her right hand holds a flaying knife (drigud) used to chop up dead bodies in cemeteries to feed to the animals—a reminder to dismember our own dualistic thinking and fixed notions. In fact, the yogini’s ornaments and implements are all remnants from the cemetery—a common locale for tantric meditation—with its reminders of death and impermanence to be converted into tools of spiritual practice leading to transformation.

I had learned the Vajrayogini charya dance a year prior to our trip. The goddess’s assured movements wielding her transformational tools (skull-bowl and chopper), conveying decisive action in the service of fearless presence, had powered me through a year of unimaginable challenges. I had emerged victorious, and I brought my personal experience of dancing Vajrayogini to her mandala.

We made the hour’s drive to the town of Pharping, about nineteen kilometers south of Kathmandu. This major Buddhist pilgrimage destination was packed with devotees of Vajrayogini bringing offerings—colored powders, food, flowers, incense, butter lamps, money—and seeking blessings at her temple. Adjacent to this Newari-style structure are sites of deep import to the Tibetan tradition: the legendary cave complex of Guru Rinpoche (Asura and Yangleshod Caves) and a Tara Temple (Drolma Lhakhang) with a self-arising Tara image.

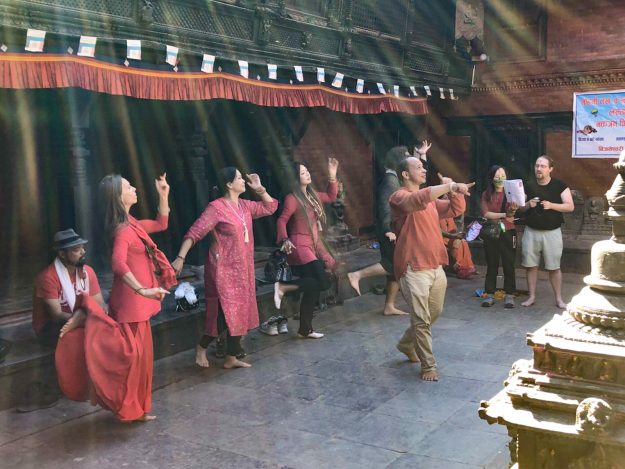

At Pharping, we initiated our danced devotions. We performed the Charya Nritya, “Dance of Refuge,” a danced prayer of refuge in the Buddha, dharma, and sangha, and “Dance of the Sixteen Offering Goddesses” at each place we visited. Sometimes we were inspired to include an additional charya dance of a particular deity as well. We had learned these dances through online or in-person workshops with Prajwal. Metaphorically speaking, we were planting these dances back into the earth where they were spawned.

The Newar village of Sankhu lies in the northeast corner of the Kathmandu Valley on the old trade route to Tibet. Here, Vajrayogini takes the form of Khadga Yogini (Sword Dakini), who wields a sword. The temple is a three-roofed pagoda with a gilt copper roof. Housed within the sanctum is the yogini statue—her red face and four arms barely peek out from beneath countless layers of adorning silks and glittering metal ornaments. The shrine room on the upper floor contains a larger gilded copper statue of Khadga Yogini, which is paraded through the town of Sankhu by the Vajracharya priests on the annual religious procession, or jatra.

More than the statues, I was taken with the gilt-copper repoussé torana above the door to the sanctum. Its central figure is Khadga Yogini in a warrior stance, her feet trampling two kneeling figures. A force not to be trifled with, her eight arms hold eight implements: an upraised sword, a lotus, an arrow, a bow, a vajra, a cattle prod, a hooked knife, and a skull-cup. She stands flanked by two more four-armed versions of herself.

Although the temple of Guhyeshwari (meaning “hidden” or “secret goddess”) contains no image of the goddess, it packs a visceral punch with its evocation of female generative energy. The temple of Guhyeshwari honors the goddess in the form of Vajra Varahi, who is a more wrathful expression of Vajrayogini. (“Wrathful” in this context indicates an energetic intensity, not an emotion.) The central shrine is believed to house her womb, which is said to sustain all of Kathmandu. A spring in the well of the central shrine overflows with red water that is said to be the amniotic fluid of the goddess. Thus, Vajra Varahi’s womb is the object of veneration here.

The half-hour flight to Lumbini allowed us to stretch the yogini mandala to include the birthplace of the historical Buddha. We made the 20-minute walk along the central avenue of Lumbini, amid the tropical woodland, up to the temple monument to Queen Mahamaya, the Buddha’s mother. The large, white, stately Maya Devi Temple marks the spot where it is said that the queen took hold of the branch of a fig tree in a flowering grove for support while she labored and gave birth to the Buddha. Just outside the temple, beside the sacred pool, we danced the charya dances in gratitude to this great mother observed by pilgrim onlookers from all over the world.

We completed the yogini mandala at Bijeshwori Temple, situated above the Bishnumati River in the Swayambhu neighborhood of Kathmandu, originally at the epicenter of an ancient cremation ground. The principal statue in the temple’s altar is of the goddess Vidyadhari (“Bijeshwori” is the Newar pronunciation), meaning “Lady of Awareness.” Frequently referred to as “Akash Yogini,” or “Flying Vajrayogini,” her body is displayed in flight, with her left leg pulled up high and her right leg behind her bent at the knee. Her left hand holds a skull-bowl to her mouth, while her right arm is extended behind her holding a chopper. She cradles a khatvanga (tantric staff) in the crook of her arm, resting it against her left shoulder.

Akash Yogini is surrounded by a sisterhood of three other yoginis. To the left of the central image is Vajra Varahi in her ecstatic dancing posture (her left foot stomps on a Hindu deity representing ignorance, while the right leg is raised up and bent), and to the right of the central image is Uddhapada Vajrayogini (Foot-in-the-Sky Yogini). The fourth yogini stands against the north wall of the temple taking the warrior stance of Naro Khechari (Naropa’s Dakini, the form envisioned by the Mahasiddha Naropa). All four yoginis hold their emblematic implements.

Our day at Bijeshwori was no ordinary visit. We were there to receive an initiation into the practice of Vajrayogini. Deity practice, also called “deity yoga,” is a Vajrayana meditation in which the practitioner adopts an archetypal role model of enlightenment (deity) to contemplate and identify with to reveal one’s own buddhanature. The ritual entry process into the tantric practice of a deity can be granted only by an empowered lineage holder, a requirement that maintains the integrity of the teachings and practices. Our initiation was performed by Prajwal’s older brother Sarbagya Ratna Bajracharya, who is a much-in-demand Vajracharya priest in Kathmandu. Prajwal served as his ritual assistant, and his extended family attended as witnesses.

After removing our shoes, we climbed the ladder-like wooden stairs to the second floor of the temple, where we sat in two rows facing the center in the long, narrow meeting room. As in the other Newar rituals we attended, we each worked with our own personal mandala, drawn onto the floor with chalk, and an accompanying platter of varied offering substances (flowers, grains, fruit, incense, water, milk, colored powders, etc.). The chalk-drawn mandala circle is a representational model of ourselves used in the ritual process. For example, we placed offerings inside the mandala to symbolically purify our body, speech, and mind as the priest and assistant chanted prayers and performed offerings to Vajrayogini. Indeed, all the ingredients we had for our personal mandalas were multiplied fiftyfold for the ministrations performed by Prajwal and his brother at the front of the room.

The two-hour ceremony came to a powerful climax when Prajwal walked down each row and one by one gave us Vajrayogini’s tools of transformation to hold—the ritual skull-bowl in our left hand and the chopper in our right. Prajwal repeated his rounds, this time placing Vajrayogini’s mark of blessing (a tika) upon our forehead, with the tip of a vajra dipped in a black paste. He attended each one of us again, placing her metal vajra crown upon our head, giving us the necessary time to fully sense it. Feeling the physical and symbolic weight of these implements made a profound impression.

I was shocked when I looked in the mirror. Wearing all of Vajrayogini’s iconographic adornments, I didn’t recognize myself.

After enjoying a home-cooked Nepali meal prepared by Prajwal’s family, we returned downstairs to the temple courtyard to dance. As we danced the sixteen offerings, I was reminded of Prajwal’s explanation, “The deities don’t need offerings. They have everything they need. Rather, the offerings serve to open the practitioner’s senses and provide us with the energy to engage in sacred practice.” We completed our celebration with the “Dance of Bijeshwori (Sky Dakini)” and its repeated flying posture just as the light rays flooding into Vajrayogini’s courtyard performed a sublime dance to complement our own.

Our pilgrimage concluded with a special performance at Itum Bahal, one of the largest Newar Buddhist monasteries in the old town of Kathmandu and headquarters of the Vajracharya Conservation Society. Unlike most travelers who come to see the sights, we were the performers, offering the charya dances back to the local community as a gift. The program was completely voluntary, and I had not planned to perform, as there seemed to be plenty of people who were eager to do so. The performers from our group decided on the deities they would dance—Ganesha, Avalokiteshvara, Green Tara, Vajra Varahi. But when I saw that no one was performing Vajrayogini, I changed my mind. I had danced her for a year; now, I would wear her red costume, bone ornaments, and dakini crown and publicly perform her dance to offer the energy she had given me.

We arrived at Itum Bahal in the late afternoon and immediately began marking our dances in the courtyard, getting accustomed to the space. When a local Charya Nritya performer arrived with a suitcase full of costumes in tow, we retired with her to one of the temple rooms to transform ourselves. I was shocked when I looked in the mirror. Wearing all of Vajrayogini’s iconographic adornments, I didn’t recognize myself.

The sun set, and the temple courtyard filled with locals and even a few tourists. The space had been set with stage lights to project the color of each deity and amplification for the two vocalists (one of whom is the chant leader from the Portland temple). They would sing the accompanying Sanskrit charya giti (vajra songs). As per our ritual, Prajwal led our group in the dances of refuge and offerings. Then we proceeded with our solos. Each dancer began by walking out toward the lit space, bowing to touch a hand to the earth, the heart center, and forehead—the gesture of gratitude and respect. Then one by one, we brought the deities to life with their dances of divine qualities and action.

The performance clearly moved those in the audience, because several days later, when most of us had headed home, Prajwal was flooded with a host of media interviews. Additionally, he was honored with several awards, including recognition for uplifting the glory of Newar ritual and its sacred dance. Prajwal is currently planning to lead another pilgrimage this spring. As for me, I now dance Vajrayogini both inside and beyond the confines of my practice room—allowing myself to acknowledge and animate the radiant Vajrayogini, who dances within me.