The Boy and the Heron begins with one of Hayao Miyazaki’s earliest childhood memories: a war-torn city on fire.

In one of the opening scenes of the Oscar-nominated Studio Ghibli–produced feature, a boy named Mahito (Soma Santoki/Luca Padovan) runs through this memory, looking for his mother, Hisako. As air raid sirens sound over 1940s wartime Tokyo, he tears toward her burning hospital, past townspeople who blur as if into ghosts. In his terror, the child does what many of us might do if we found ourselves alone in a world seeming to end all around us: he calls out for his mother.

The story that unfolds follows Mahito in the aftermath of his mother’s death as he moves to the Japanese countryside with his father, Shoichi (Takuya Kimura/Christian Bale), to live with his pregnant stepmother (and Hisako’s sister), Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura/Gemma Chan).

There, against a haunting soundscape composed by Joe Hisaishi, Mahito wavers between rigid waking moments and harrowing flashbacks to fire. In the filtered bucolic light shining through Miyazaki’s hand-drawn forest, the child’s grief is anatomized. It spills out in tears as he falls asleep, and in blood—in one of the more bracing scenes—when he injures himself with a rock. While his new stepmother tries to win his affection and his father builds warplanes at a factory nearby, Mahito churns in an expanse of suffering laid bare by the rural quiet. No one in his life—not Shoichi, Natsuko, or the seven sprightly grandmothers who haunt the countryside estate—seems able to reach him.

But soon, one voice pierces through it all: the gnarled call of a shape-shifting gray heron (Masaki Suda/Robert Pattinson)—a trickster archetype—who stalks Mahito from the moment he arrives and tells him his mother is still alive. When Natsuko disappears one day, Mahito follows the heron through an abandoned tower into a spirit world in dubious hopes of finding them both.

One of Miyazaki’s more autobiographical films, The Boy in the Heron is an elegiac tale from a beloved director returned from retirement (again) to tell (at least) one more story. As Mahito moves through his grief in search of his mother, we witness Miyazaki processing his own mother’s death from tuberculosis in 1983, conversing with his own father, who made rudders for fighter jets during World War II. Through Mahito’s eyes, Miyazaki dilates the unparalleled and nauseating mysteries of birth, death, attachment, and loss, meditating on themes he is often in conversation with in his films (among them: Spirited Away, Princess Mononoke, and Ponyo), such as impermanence, change, and what it means to lose and look for the ones we love.

While Mahito knows the claim that his mother is alive is “clearly a lie,” he follows the heron through the tower’s dark, librarial passageway, pulled by a need “to make sure.” As Mahito sinks through the floor of the tower via a watery, womblike passage, he enters a spirit world guided by a similarly paradoxical logic. There, the faceless dead share a cursed ocean with hungry pelicans, neofascist parakeets, unborn creatures called warawara, and beings from every timeline of the multiverse.

In this realm, the film’s plot becomes notably improvisational. The heron disappears and reappears, offering comedic relief and a quirky portrait of moral ambiguity. Mahito meets Kiriko (Ko Shibasaki/Florence Pugh), a younger version of one of the seven grandmothers, and Himi (Aimyon/Karen Fukuhara), a maiden version of Hisako, both of whom take him under their wings. A mysterious tower master (Shōhei Hino/Mark Hamill)—Mahito’s great-granduncle, who entered the tower around the time of the Meiji Restoration—stirs in the background of the story, brooding like a god behind a giant curtain.

At times, there seems to be little narrative clarity driving Mahito’s movement through this world, but that might be the point. As he looks for his mother and Natsuko, forces of death, care, and consumption propel the plot more than any sort of linear quest. Mahito stands knee-deep in the ocean, catches and carves a giant fish, and is smothered by pelicans who push him toward a tomb. He receives and offers food. He learns to bury the dead. Slowly, he sheds the military uniform he wears. Smaller journeys begin and end and Mahito experiences them, becoming a witness to samsara. Here—Miyazaki seems to say through the hum of these unfolding images—is a world not at all unlike our own.

Throughout the film, Mahito’s search for his mother is tied to a search for an answer to the question that the film’s original Japanese title posits, referencing Genzaburō Yoshino’s 1937 novel: “How do you live?”

Perhaps more specifically, The Boy and the Heron asks, how do you live in a world where everything changes and everything ends? Where mothers are set on fire before their children’s eyes? While the filmmakers’ cinematic exploration of this existential impasse seems to follow the logic of dreams, it is not an abstract question. Miyazaki was not the last child born whose first memories are of war.

When the New York Times Style Magazine asked Miyazaki if the film would offer a resolution to its Japanese title, he said, “I am making this movie because I do not have the answer.”

But if the film itself offers an answer, it may be connected to what it means to entangle oneself in a changing and impermanent world.

While Mahito’s great-granduncle appears to have sought meaning through control—sitting atop the tower, stacking magic stones that determine the stability of the universe—Mahito is learning to be present to suffering, rather than resist it. Although this is a dreamworld, his lost mother does not magically reappear. To live, Mahito sees through the cyclical churn of the dreamworld, is to die. To love is to experience loss.

Yet in the background of the film, a larger sense of meaning seems to stir. Death is a part of life, the story says, but life is also a part of death.

While Mahito may have longed for the enchanted heron to prove that his mother hadn’t died, he is ultimately shown that he can feel loved even though she did. Beyond accepting impermanence, Mahito is honing an ethic of care and commitment to loving a world that will inevitably end.

“Your presence is requested,” the heron caws, and in the dark of the Manhattan theater where I watched the film for the second time, I heard this phrase in more than one way. As the heron summons Mahito, he also calls the boy into relationship with the world—into presence. It is not enough, he suggests, to live on as a ghost.

I think about this toward the end of the film when Mahito’s search for his mother and for Natsuko suddenly collide. In a delivery room at the base of the tower, which is simultaneously a tomb, Mahito claims Natsuko as his new mother. As he is symbolically reborn, consciously accepting a life of birth, death, attachment, and loss, it becomes clear that the heron’s lie was also, in some way, true.

As my image of Mahito’s mother blurs and disperses during this scene, I begin to wonder if Mahito’s mother was actually present in the story in more ways than I had originally imagined.

In most cultures, mother is the name given to a female caretaker of children, archetypically caring, protective, nurturing. But often, the common definition of the word leaves little room to access what may be the truth of motherhood—that sometimes the bodies we emerge from are not our mothers. That those bodies can be mothers and monsters at the same time. That the ones who offer us love and care as we grow could be anything, and are often more than one thing. The archetype of the mother as a figure embodying the source and sustenance of life was present in cultures around the world long before Western conceptions of patriarchal gender norms and the pervasiveness of the nuclear family relegated the term to certain bodies alone.

The word mother is also connected to the word matrix. Anciently translated to mean womb, a matrix refers to a place or set of conditions where things form. Wombs, I imagine, then, might not just be a bodily organ but any threshold through which we pass into new or changed life. “Maybe when we say mothering,” Alexis Pauline Gumbs writes in the book Revolutionary Mothering, “we really mean ‘the creative spirit’ or ‘love’ itself.”

“Did you know we have all been each other’s mothers?” an elder I once lived with in New Mexico asked as we stood together one morning, feeding her goats. “We’ve each reincarnated so many times that I’ve been your mother and you’ve been my mother, and even she has been our mother,” she said as she pointed to the doe, who brayed. She shooed some flies away. “Them too.”

This worldview, I later learned, is described in the Mata Sutta, a passage of the Pali canon, which says, “A being who has not been your mother at one time in the past is not easy to find.”

In one scene toward the end of the film, Himi, Natsuko, and Kiriko stand with Mahito in a hall full of doorways, and I see a mother refracted through all three of them. Maybe, I venture, as the ocean slits open and resembles water breaking, the way the world inevitably falls apart is also some kind of birth.

We all want the world to be more like a mother and less like a war zone. If only every being could come home at the end of our lives to something vast and loving—to a death that is gentle, not fiery, not bodies ripped apart or crushed under rubble, not senseless or malicious, not children. But through Mahito’s eyes, we see a world that is monstrous at the same time as it is loving. It is a world that, much like our own, does not make sense no matter how hard we might try to understand it.

It is this world that mothers us and that kills our mothers, calling to us through a heron’s unhinged jaw. It is this world where we will die and it is this world where, if we are to live, we must live—where living is possible because of the people we love, who, in countless ways, bring us to life.

Through Mahito’s eyes, we see a world that is monstrous at the same time as it is loving. It is a world that, much like our own, does not make sense no matter how hard we might try to understand it.

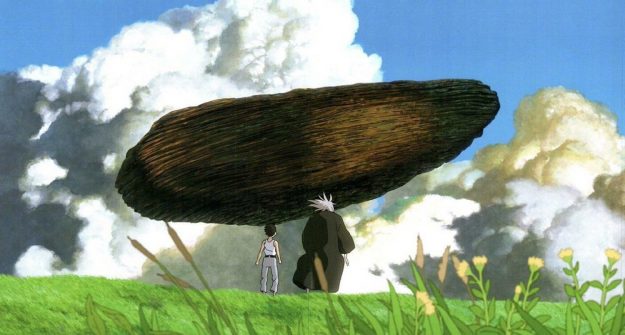

In one of the final scenes of the film, Mahito stands on a windy hillside beneath a floating black stone that pulses with the power of the universe. There, his great-granduncle offers him his legacy as the stacker of the sacred stones. Mahito will have the chance to build his own tower, his ancestor tells him, and make “a kingdom that is free from malice,” but the boy has learned there is no such thing. “These look like gravestones,” he says, revealing what the spirit world has shown him: suffering and death are already embedded in all things.

“So you would rather return to a chaotic world of murderers and thieves?” the tower master says. “Soon your world will be a sea of flames.” But Mahito has learned of a love more powerful than fear—a love that compels his mother to walk through a door that leads to fire, again and again, so that Mahito’s door might lead somewhere else. Through that door, Mahito will return home to his own time with his friends, already knowing what his ancestor does not yet understand: you cannot make a perfect world from a tower in the sky.