Between-States: Conversations About Bardo and Life

In Tibetan Buddhism, “bardo” is a between-state. The passage from death to rebirth is a bardo, as well as the journey from birth to death. The conversations in “Between-States” explore bardo concepts like acceptance, interconnectedness, and impermanence in relation to children and parents, marriage and friendship, and work and creativity, illuminating the possibilities for discovering new ways of seeing and finding lasting happiness as we travel through life.

***

“There are so many stories in the world just waiting to be told,” says Jadu, one of the protagonists in Amitava Kumar’s new novel, My Beloved Life. The book interweaves narratives to tell a tale that spans decades and countries: the story of Jadu, a history professor born in rural India in 1935 (like Kumar’s father); of his daughter, Jugnu, an Atlanta journalist who returns home after her father’s death to learn about his past and report on the pandemic; and of India’s political and social landscape before and after Independence. In a testament to the power of storytelling and bearing witness, Kumar explores how we find meaning as we navigate change and loss, endings and beginnings, in both our personal and collective lives.

Born in 1963 in Ara, India, Kumar is a novelist and a poet, a memoirist and a journalist. His previous novels are Immigrant, Montana (2018), a New Yorker and New York Times book of the year, and A Time Outside This Time (2012); his nonfiction books include Every Day I Write the Book (2020), A Foreigner Carrying in the Crook of His Arm a Tiny Bomb: A Writer’s Report on the Global War on Terror (2010), and Husband of a Fanatic (2004). He has received many awards and honors, among them a 2023–24 Cullman Center Fellowship, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Ford Fellowship. He lives in Poughkeepsie, New York, where he is the Helen D. Lockwood Professor of English at Vassar College.

In a recent Zoom conversation, Kumar talked with me about coming to terms with his father’s death, reclaiming what he lost when he immigrated to America, and how art can be a site of both mourning and hope.

*

The bardo teachings are about living our lives as well as possible. Your father died last year, and at the end, what you felt most strongly was the desire to express your gratitude to him for showing you the right way to live. What is that way? My father was born in a hut and didn’t see an electric bulb until he was 8. From this poor background, he rose in life. What he taught me and my two sisters is the choice of a simple life, a frugal and honest life, a sort of unremitting labor.

Did you take that lesson to heart? I think I did. I’ve never felt the lure of capital, of a luxurious life, of power and giving orders to others.

Often we also want to diverge from our parents and not carry certain legacies forward. You’ve said that because your father was quite formal, he didn’t talk with you about things like death or love. Now that you’re a father, do you want a different kind of relationship with your son? I feel I should be a different kind of parent. I talk much more, even about death. In fact, my son just the other day asked me what rituals I would like him to do when I die. He’s only 15. I thought, “Oh my god! Maybe I’ve been too open.” I want him to be free of the idea that I might keel over and die tomorrow. Then, yesterday he asked me to shave off this fuzz that had appeared on his face. I said, “I don’t want you to grow up so fast.” But because he wanted me to, I shaved him. I thought he would look younger, but instead, he began to look older, and I said, “Where has my baby gone?” And he said, as if he were my teacher, more detached, “Dad, you have to let go of my hand.”

You returned to India to carry out the funeral rituals for your father. What effect did that have on your view of the role of ritual? I wrote an essay on my mother’s death called “Pyre” that was published on Granta.com about ten years ago. The editor at that time, Ian Jack, said that one thing that was coming across in my description of the ritual was that Indians confront death more directly. Maybe that is correct. In the case of the death of my parents, what the ritual did—sitting next to the body, lighting the pyre—was to slow down what was happening and make me aware, allowing me to bring grief up close and work through it, instead of shunning it.

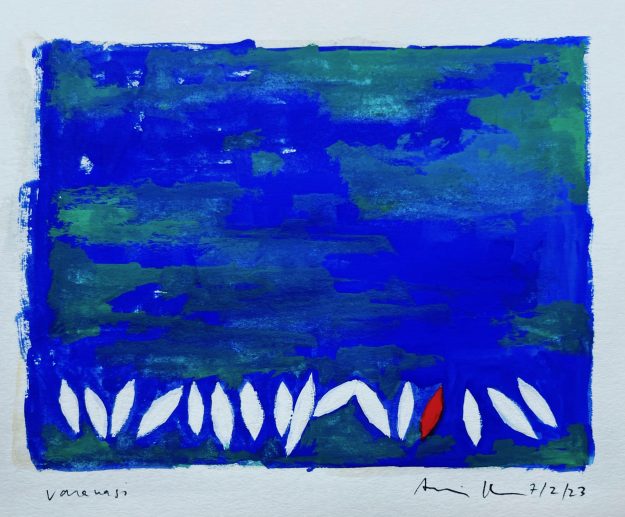

With my father’s death, I went back to India a few months later and revisited Varanasi, where we cremated him, so I could occupy that moment more fully, offer a prayer again, and write about it. I’d already been thinking a lot about ritual, and writing about it, because I felt I needed to write about the hundreds of thousands in India who died without ritual in the pandemic. I tried to do that in My Beloved Life, to acknowledge the nameless people who died without receiving attention or sympathy from the powerful, just bodies that were buried beside the Ganges. I wanted my novel to, in my own modest way, be a memorial and to note the desire for ritual, to be a site of that kind of mourning.

In your novel, there’s an epigraph from Philip Larkin’s poem “Aubade”:

“The sure extinction that we travel to

And shall be lost in always. Not to be here,

Not to be anywhere,

And soon; nothing more terrible, nothing more true.”

Do you fear death? Does it seem terrible? I used that epigraph because it seems to get at a fear of death, of endings, that grips so many of us. From childhood, I gave a lot of thought to, “What will happen if my parents die?” And when my kids were young, I feared they would die. I wanted to acknowledge that.

Do I feel fear of death in the extreme way described in “Aubade”? No. And rather than feeling afraid when my father was dying, I found it comforting to be next to him. He was in the ICU for fifteen days, and I arrived a couple of days after he was put on the ventilator. The doctor said, “Talk. Sometimes they can hear you, so please keep talking to him.” I had never said “I love you” to my father, but now I was able to say this, in my own dialect. I said things like, “We are all here. Do not give up hope. If you can hear me, you should know there is good care for you. We are all here, and everything is okay.”

My birthday fell in the middle of it, and my sisters felt my father would have wanted me to cut a cake. I thought it was ridiculous, but they insisted, out of love or desperation. I have a photograph in which I’m cutting a cake at midnight next to my father’s comatose body, and my sisters are standing on either side of me. It was a reminder that there is death, and there is commemoration of life, both happening at the same time. That is reality, and it is good to stand in the middle of the stream and live rather than stand on the bank and witness things from afar, to have both a sense of participation and also a sense of wise detachment because one knows the reality of things.

You’ve gone back often to Patna, the city in India where you grew up. Now that your parents have passed, will you return less often? For the longest time, I felt—maybe I still do—that for me, the real stories are in India and I am distant from what’s taking place. That feeling of alienation has been very strong, the sense that I’m losing out. So I would like to continue to go back.

In 1995, I read of the sarin gas subway attack in Japan. At that time, Haruki Murakami was teaching in the US. He decided to go back to Japan and do some interviews. For him that was a way of reentering, or entering, a wound in the national psyche—a way of entering the life of his country. I took that as a lesson. So when there were riots in Gujarat in 2002 and nearly 2,000 Muslims were killed, I went back to India and did interviews. In 2005, I published Husband of a Fanatic: A Personal Journey Through India, Pakistan, Love, and Hate. At the beginning of that book, I talked about how going back and interviewing people was an attempt to reclaim some of what I’d lost, to understand the conflicts taking place, and people’s suffering and the ways in which they might or might not have made peace with it.

“It is good to stand in the middle of the stream and live rather than stand on the bank and witness things from afar”

You’ve written in your Substack blog about a 1948 painting by Krishen Khanna called News of Gandhiji’s Death, a work that poet Ranjit Hoskote says “suggests the possibility of ‘solidarity of grief.’ ” The painting shows people reading newspapers under a streetlamp after the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi. “What we see,” you write, “is a public gathering of people absorbed by a singular tragedy. Gandhi, whether you agreed with him or not, had brought people together. Looking at the painting, one can imagine there exists a possibility of a space available for public discussion.” You’ve talked about your novel as a site of mourning. Can you say more about how art makes space for public discussion, for solidarity of grief? Well, let’s think of recent historic tragedies, like 9/11, of the discussions that were acts of mourning, often involving poetry. The number of times W.H. Auden’s poem “September 1, 1939” was circulated in the days immediately after 9/11 was amazing. Some wonderful poems, including “Resistance” by Simon Armitage, made the rounds after the Ukraine war started. Palestinian poet Refaat Alareer’s “If I Must Die” has been shared thousands of times, translated into many languages.

There’s so much suffering in the world, so many crises and tragedies. In the face of this, art as pedagogy, art as beauty, art as peace or seeking of peace can enhance human life. It can allow us to linger in places of feeling, of both sorrowing and hope.