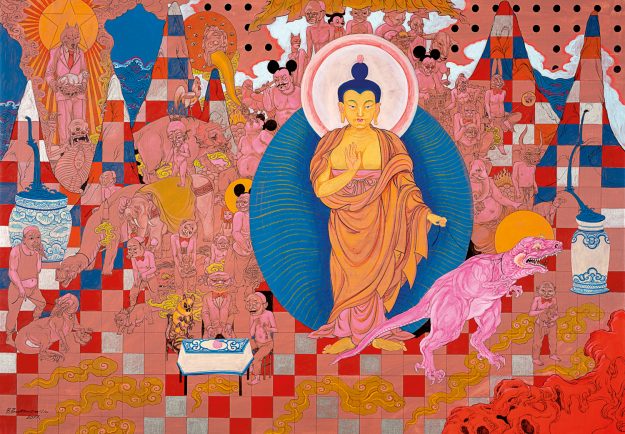

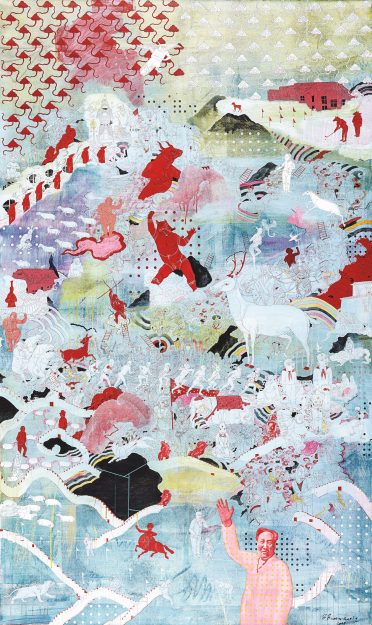

Nomadic horsemen, astronauts and spaceships, wolfmen playing golf, devils in long johns, animal-headed men in business suits, reindeer, sheep, elephants, giant fish, fantastical creatures, even the odd dinosaur are just some of the images filling the outsized canvases of Mongolian artist Baatarzorig Batjargal. Rendered in vivid acrylics, the paintings teem with “gods and holy men, artists and intellectuals, warriors and noblemen, politicians and oligarchs, sumo wrestlers and robots,” as one gallerist put it. Notable figures from history and pop culture include Mao Zedong, Sigmund Freud, Mickey Mouse, the Buddha, and Vajrapani, the fierce Tibetan Buddhist deity revered as the protector of Mongolia. Saints and sinners alike are among the meticulously executed figures. Batjargal does not judge. Good and bad, “they make up the whole of life,” he says.

Saints and sinners alike are among the meticulously executed figures.

The paintings on these pages are prime examples of the 41-year-old artist’s satiric social commentary in visual form. His multilayered imagery reflects the fractured history of Mongolia in the past century, when the ancient nomadic culture and Buddhist religion were swept away under Soviet domination, until liberation in the early 1990s brought capitalism and a new challenge—rampant consumerism.

Batjargal’s response to the loss of cultural heritage and rapid regime change is Mongol zurag painting. Based on a style that arose in the Mongolian independence movement of the 1920s, contemporary zurag revives traditional forms in the context of current concerns. The paintings of Batjargal and other zurag artists, including his wife, Nomin Bold, are recognizable by their bright colors, delicate brushwork, and flat perspective, incorporating elements of Tibetan thangka art, the dreamy landscapes of Chinese guo hua painting, and the equestrian paintings of the Khitan people, who once dwelt in central Asia.

Born in 1983, Batjargal grew up in Mongolia’s capital, Ulaanbaatar, where he shares a home and studio with Bold and their three children. His birth name, Baatarzorig, means “brave hero”: fittingly, his interest in zurag was triggered, he says, by paintings showing epic battles and Mongolian warriors. “‘Maybe I can depict some heroes,’ I thought.”

Nomads on horseback are omnipresent, symbols of the way of life Soviet socialism destroyed.

Melding reality and the dream world, Batjargal’s art reflects far-reaching influences, including concerns about social inequality and the environment and a passion for myth. The dragon, a symbol of strength, is a recurring image, rendered as a dinosaur in paintings like Buddha’s Garden and Soft Triangular. Other recurring images include the Buddha and shamanic figures. Spiritually, “I’m in the middle between Buddhism and shamanism,” he says. “Buddha’s presence in the art represents love of the universe, but I’m questioning the society we live in, with all the religious beliefs and motifs, in contrast to the society with all the wrongdoings.” In Soft Triangular, a Noah’s ark packed with humans signifies Judgment Day; he calls the painting “a vision of the COVID global pandemic.”

Nomads on horseback are omnipresent, symbols of the way of life Soviet socialism destroyed. In Law of Nature, the central figure “represents Central Asian nomads who lost their way,” Batjargal says. “The idea is to reestablish union with nature.” It was, in fact, a nomad horseman, Batjargal’s uncle, who introduced him to art at a sculptor friend’s studio. Later, a teacher, recognizing the boy’s talent, recommended he study drawing. Batjargal earned a BA in fine art from the Mongolian University of Arts and Culture in Ulaanbaatar in 2005. He studied Western art for two years, and figures like the bikini-clad woman in MGL and people in Mickey Mouse ears allude to consumerist influences.

It’s all part of the vast tapestry of humanity and its artifacts in the intricate canvases of a master storyteller.