Think of “Buddhist art,” and what probably comes to mind are historic artifacts of Asian cultures. Antiquities from illuminated manuscripts to scroll paintings and sculpture define Buddhist art in the obvious sense that they give direct expression to stories or doctrine rooted directly in Buddhist tradition. But where and how does Buddhist understanding inform contemporary Western art? These questions become even harder to answer when we consider that a Buddhist influence has migrated westward only recently. Some examples spring readily to mind: Morris Graves and John Cage have avowed the influence of Buddhism and the arts of Asia on their work. Graves adapted Japanese ink-painting techniques to make poignant yet cartoon-like images of wildlife. Cage, by using chance procedures in his visual art as well as his musical compositions, sought forms and order free from his own taste and judgment. But apart from these famous instances, how in modern Western art does a Buddhist influence manifest itself, irrespective of the creator’s professed spiritual awareness?

Can art with Buddhist content be made where there is no Buddhist tradition? If a devout Tibetan painter living in America, for example, happens to make a tanka in the time-honored manner—surely it must be counted as Buddhist art. In such a case we might say that the painter himself, by dint of his craft and beliefs, embodies the tradition in which he works. However, the reception of his work, outside the Buddhist community, is another matter: uncomprehending viewers may well mistake canonical images for exotic decoration. And the votive intent of the work may be obscure to people who do not share the painter’s assumptions about the communicative—and causative—potential of sacred imagery. In the Tibetan tradition, for instance, all art is spiritual in intent and significance: symbolic structures to aid meditation, to personify and unveil subtle aspects of existence, to promote specific stages of spiritual awakening or to heal mental infirmities. Such a sense of artistic purpose may seem as esoteric (or unfeasible) from a Western secular vantage point as the codified meaning of a Tibetan religious image.

In the West, prevailing notions of art’s function tend to be vague, superficial, and malleable, not least because art’s production and reception are founded on commerce, novelty, and the view that the morality of culture is, like aesthetic response, largely a private matter.

In iconography and intended function, then, there are no ready analogies between Asian traditions of Buddhist art and the visual arts of contemporary America or Europe. No mere “appropriation” of Buddhist imagery (nor even its sincere adaptation) by Western artists yields what might be called Buddhist art (or content). Yet anyone who believes Buddhist insight to be universal must wonder whether some modern Western art has spiritual value from a Buddhist point of view.

The commonsense view that suffuses most of American life is startlingly Cartesian: it assumes that the body is physical and public, while the mind is intangible and private, and that, because matter and physical sensation are the presumed touchstones of all quiddity, intangibles are accorded reality only when some sort of worldly authority endorses them. These curious assumptions receive constant reinforcement through the isolation, competitiveness, and restlessness instilled by institutional structures of American life, from the banking system and the consumer economy to mass education and entertainment. At every level, dualistic thinking is affirmed and reiterated as if it were plain truth.

It is almost inevitable, then, that in America people bring to the arts a sense of mortified, malnourished subjectivity. What they hope for, and very often all they take from art, is the warmth of an implied respect for inwardness that is little in evidence in the rest of the culture. Frustration often follows the discovery that static visual art cannot overcome the passivity of its audience, that it depends on a mindful engagement which, in feeling, may offer a foretaste of relief from the presentation of reality as unfathomably particulate. The demand for mindfulness that good art makes, if only in a rudimentary way, points to the fact that works of modern Western art have their uses as spiritual devices. So does the popular intuition, however poorly understood, that art may exert a healing influence.

Some critics see a therapeutic animus in modern secular Western art, pre-eminently that of the turn-of-the-century European avant-garde. Donald Kuspit, for example, argues from a psychoanalytic perspective that “belief in the healing power of art is the cornerstone of modernism, as if its revolutionary transformation of art demonstrates the power of art to transform the individual’s life for the better. This is, indeed, the ultimate rationale for modernist utopianism.” For Kuspit, unvoiced spiritual need explains art’s appeal in a culture where its social function is ill-defined. “True art seems to care about inner life and respond to narcissistic need. It thus makes people feel inwardly alive, renewing their faith in themselves.” This point about the liberating playfulness of “true” art is echoed in some of D. T. Suzuki’s writings on the therapeutic character of Zen:

Zen, in its essence, is the art of seeing into the nature of one’s being, and it points the way from bondage to freedom. . . . We can say that Zen liberates all the energies properly and naturally stored in each of us, which are in ordinary circumstances cramped and distorted so that they find no adequate channel for activity. . . . It is the object of Zen, therefore, to save us from going crazy or being crippled. This is what I mean by freedom, giving free play to all the creative and benevolent impulses inherently lying in our hearts.

Many examples may be found of modern Western art whose intent is to create a psychological openness in which one’s faculties may sense their capacities and claims on instinctual energy.

Two points of difference, though, may outweigh ostensible parallels between the healing aims of avant-garde modernism and the exemplary qualities of Buddhist art. One is that modern Western art is allied with the individual ego’s struggle to shore itself up against a society that denigrates the inner life, while traditional Buddhist art, especially that inspired by Zen, reflects the idea that subjectivity, rather than being an ultimate value, may be the obstacle to liberation, especially if it is identified with a superior sense of its own rationality.

A second point of difference is that the spiritual function of traditional Buddhist art is supported by a community (implicit, at least) of adherents. In the context of Western modernism, encounters with artworks tend to deepen an individual’s sense of solitariness, which—thanks to aesthetic richness—may yet come as a respite from the solitariness that ordinary life in mass society imposes. Contemplative activity in Western culture connotes withdrawal into subjectivity, a deepening of the dualism that is taken to define individuality. The dualistic tenor of aesthetic experience has long been reinforced by the modernist emphasis placed on the “autonomy” of the artwork.

It is misleading to ask how we might recognize artworks in the modern Western context as Buddhist in spirit or insight, not because there are none, but because “recognition” implies that certain signal images or other qualities might resolve the matter. But to “recognize” Buddhist insight in Western art is too passive an expectation, for such “recognition,” where it occurs, will result from the right kind of participative attention. How specific artworks demand we use our attention, is a more promising question.

My own temptation to view canonical images and symbols as the true marks of Buddhist art reminds me of the story of the eighth-century monk from Tanxia, subject of some notable Zen-inspired paintings (such as the one by Unkoku Togan (1547-1618) in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art). On an especially cold day, lore has it, the monk from Tanxia, short of fuel, threw a wooden statue of the Buddha on the fire to warm himself. Scolded for his impiety by the temple abbot, the monk replied that he had burned the effigy to obtain sharira (ashes of the Buddha, regarded as sacred relics). When the abbot asked the monk in exasperation how he expected to get sharira from a common piece of wood, the monk answered with a question of his own: why blame him then for burning an ordinary piece of wood?

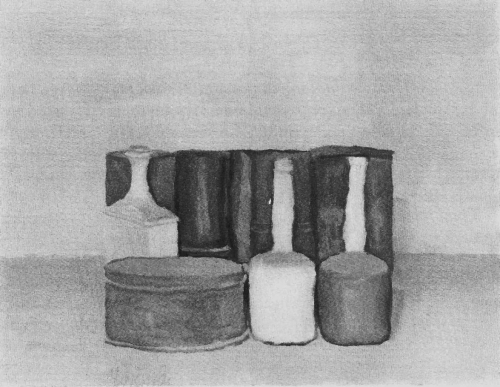

Zen iconoclasm reminds us that if we look for Buddhist art in unlikely places (or times), we must be prepared to find it in unlikely forms. As an example, consider a 1954Still Life by the Italian painter Giorgio Morandi (Smith College Museum of Art). The painting depicts, from direct observation, a tight cluster of objects—some tall canisters, a boxy vase with a narrow, flared neck, a round cake tin, and two long-necked bottles—from the repertoire of common items that Morandi recombined in painting after painting for decades. In the style typical of Morandi, the softly lit objects are delineated without haste. In fact, the calm quiet of the painting is its most striking aspect. It does not evoke the appearances of things so much as the sensation of paying attention to them until their separateness—from each other and from the act of observation— recedes. Morandi transmits that sensation by a subtle ambiguity of figure and ground, as the two long, light-colored bottlenecks against the dark canisters behind almost detach themselves to read as channels of empty space, rather than opaque volumes. He calls attention to the arbitrariness of the still-life painting exercise by grouping the objects together so that their collective profile is a rectangle echoing the shape of the painting itself. By all these devices, he telescopes his process of studying the objects, the painting of what he sees, and our observation of the painting. What results is an evocation of meditative release from judgment and from the driven quality of perceptual habit.

A unique aspect of Morandi’s work is its use of descriptive representation to achieve an effect opposite to that of most representational art. Rather than endorse the discrete reality of the thing depicted—and of the depiction itself as a thing—Morandi produces a feeling of communion with the ordinary. Morandi’s focus upon the tempo and the timbre of consciousness as determinates of individual experience—and of wider human affairs—has a force familiar in Buddhist perspective.

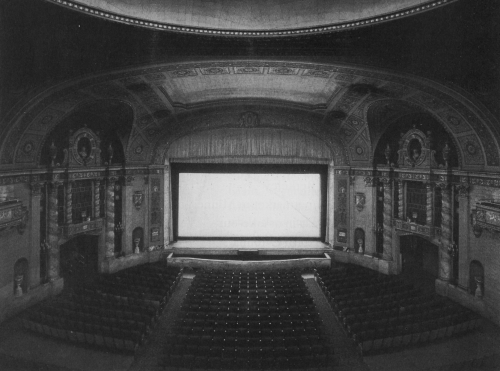

Photography, by contrast, may seem to lend itself to uses that serve directly, in social impact, the Buddhist aim of advancing compassion. But Hiroshi Sugimoto’s U.A. Walker, New York (1978), for example, is plainly more artistic than documentary in intent. It is part of a series of pictures of the ornate interiors of old movie theaters. Shot from the balcony, this picture shows the baroque decor of a vast movie house, complete with orchestra pit and domed ceiling. The whole space is illuminated by reflected light blazing from the empty rectangle of the movie screen. At a glance, it appears that the screen is lit by the projector lamp—yet no film is passing before it. But look longer and you sense that the brilliance of the screen is inordinate, almost blinding. The screen comes to seem like an opening into a different dimension, as in a sense it is: an opening into a dimension of totally illusory cinematic (and therefore photographic) experience. In its radiance, the screen becomes a figure for intuition that all worldly experience may be illusory.

This interpretation is supported by the way Sugimoto works. His theater pictures result from very long exposures: each lasts as long as an entire movie. In fact, what blazes from the screens in his photos is the sum total of the light projected onto them in the course of a movie showing. Choosing his aperture accordingly, he leaves the lens open through the duration of a screening.

In both these examples, and in many others we might consider, the bounds of the art object appear well defined. If we are looking for what might be called Buddhist content in modern Western art, our inquiry will proceed along lines such as those traced above—if we take it for granted that art comprises a special class of objects. But an opposing tendency is to define art in terms other than the particularities of an object or the material end-product of a skillful performance. In the twentieth century, “art” has become increasingly open to redefinition according to extra-aesthetic interests. And while this tendency may seem to frustrate a search for “Buddhist” insights in contemporary Western art, the opposite may be true.

The secularization of society in the West since the seventeenth century gradually stripped the visual arts of their traditional functions. Formerly, artists answered the ecclesiastical demand for compelling visions of Christian belief and royalty’s need for images to radiate its eminence. With the modernization of European society, artists found themselves displaced into a market economy, to produce luxuries of uncertain function and debatable value for a small, quixotic public. With the momentous influence of the Romantic movement, the autonomous art object came to be treated as a more or less direct expression of the artist’s personality. Definitive examples might be found in the work of Vincent van Gogh and the early German Expressionists and, much later, in the art of the American Abstract Expressionists around the turn of the fifties.

Backlash from the Expressionist position began around the time of World War I, foreshadowing the present climate in which the very notion of selfhood (as a fount of authorship, anyway) is regarded with suspicion (politically rather than spiritually) and the concept of art has become almost anarchically accommodating. As Arthur Danto describes it, “In periods of artistic stability, there can be little doubt that works of art very frequently were found to have properties, failure of which would seriously call in question their status as artworks. But that time has long since passed, and just as anything can be an expression of anything, provided we know the conventions under which it is one and the causes through which its status as an expression is to be explained, so in this sense can anything be a work of art. The typewriter I am writing on could have been a work of art, but it happens not to be one. What makes art so interesting a concept is that in nothing like the sense in which my typewriter could be a work of art could it be a ham sandwich, though of course some ham sandwich could be, and perhaps already is, a work of art.”

The present uncertainty about how art is to be defined, who defines it, and for how long, is uncomfortable, but it may mean that Western art is more likely to become an inadvertent vehicle of Buddhist insight than ever before. For, rather than see artworks in proud isolation against a background of mundane incoherence, people in the field are increasingly inclined to regard them as peculiar consequences of larger forces and frames of reference: material, social, even spiritual. It is as if, around the issue of the nature of art, many people have acccepted in some measure the point articulated by Thich Nhat Hanh in his commentary on theHeart Sutra. Of the well-known paradox declaring that “form is emptiness, emptiness is form,” he asks what forms—the entities we regard as real—are empty of? His answer is that they are “empty of self-existence,” at least in an expanded view, being connected somehow to everything else that is.

Remarkably, many people (at least within the art world) have lately come to believe that, in order to be seen understandingly, artworks must be viewed as embedded in great networks of relations with other forms and forces. This recognition itself is part of what makes it difficult to decide now what is and is not “art.”

To say that there is Buddhist content in Western art is generally inaccurate, though there are curious exceptions, such as the work of the German artist Wolfgang Laib, a professed Buddhist, who sees his installations of accumulated pollen as spiritual expressions. What may be said fairly is that seemingly unlikely examples of Western art lend themselves to vivify the spiritual understanding of someone who happens to bring to them a Buddhist point of view.