It is January 1991, twenty-three minutes after I injected a large dose of DMT (N,N-dimethyltryptamine) into Elena’s arm vein. Elena is a forty two-year-old married psychotherapist with extensive personal experience with psychedelic drugs. DMT is a powerful, short-acting psychedelic that occurs naturally in human body fluids, and is also found in many plants. Elena has read some Buddhism, but practices Taoist meditation.

She lies in a bed on the fifth floor of the University of New Mexico Hospital General Clinical Research Center. The clear plastic tubing that provides access to her vein dangles onto the bed. The cuff of a blood pressure machine is loosely attached to her other arm, and the tubing snakes its way into the back of a blinking monitor.

Within thirty seconds of the injection, she loses awareness of the room, and us in it. Besides myself, Elena’s husband, who has just undergone a similar drug session, and our research nurse sit quietly by her side. I know from previous volunteers’ reports that peak effects of intravenous DMT occur between two to three minutes after the injection, and that she will not be able to communicate for at least fifteen minutes, by which time most effects will have faded. Her eyes closed, she begins spurting out laughter, at times quite uproarious, and her face turns red. “Well, I met a living buddha! Oh, God! I’m staying here. I don’t want to lose this. I want to keep my eyes closed to allow it to imprint itself. Just because it’s possible!”

Elena felt great the next week. “Life is very different. A buddha is now always in the upper right-hand corner of my consciousness,” says Elena. “All of what I have been working on spiritually for the last several years has become a certainty. Left hooks from the mundane world continue to come up and hit me, but the solidity of the experience anchors me, allows me to handle it all. Time stopped at the peak of the experience; now everyday time has slowed. The third stage, that of coming down from the peak, was the most important; if I had opened my eyes too soon I wouldn’t have been able to do as much integrating of the experience as I have.”

Two years later, Elena rarely takes psychedelics. Her most positive recollection of the DMT session was the “clarity and purity of the medicine.” The most negative: “The absolute lack of sacredness and context.” Many of the changes in her life, particularly a deepening shift from “thinking” to “feeling,” were “supported” by the DMT session, but were underway before it, and continued after it.

Elena’s experience, repeated by 10 to 20 percent of the volunteers in our psychedelic drug trials, represents the most gratifying and intriguing results of our work in New Mexico. My own interest in Buddhism and psychedelics meet in the most positive way in her DMT-induced “enlightenment experience.”

Ours was the first new project in twenty-five years to obtain U.S. government funding for a human psychedelic drugs study. This scientific research was the result of eighteen years of medical and psychiatric training and experience. I also have been practicing Zen Buddhism for over twenty years. And it is in the molecule DMT where these two interests have finally merged.

There are important medical reasons to study psychedelic drugs in humans. The use of LSD (“acid”) and “magic” mushrooms (which contain psilocybin) continues to climb. Understanding what psychedelics do to brain function, and how, will help treat short- and long-term negative reactions to them. Because there is some similarity of symptoms between psychedelic drug states and schizophrenia, psychedelic drug research also may shed new light on this devastating mental illness.

There are other reasons to study psychedelic drugs. Although less “medical,” they do relate to health and well-being. Primary among them is the overlap between psychedelic and religious states. I was impressed by the “psychedelic” descriptions of intensive meditation practice within some Buddhist traditions. Because their scriptures did not mention drugs, and the states sounded similar to those resulting from psychedelic drug use, I suspected there might be a naturally occurring psychedelic molecule in the brain that was triggered by deep meditation.

I was led to the pineal gland as a possible source of psychedelic compounds produced under certain unusual mental or physical states. These conditions would include near-death, birth, high fever, prolonged meditation, starvation, and sensory deprivation. This tiny organ, the “seat of the soul” or “third eye” of the ancients, might produce DMT or similar substances by simple chemical alterations of the well-known pineal hormone melatonin, or of the important brain chemical serotonin. Perhaps it is DMT, released by the pineal, that opens the mind’s eye to spiritual, or nonphysical, realities.

The pineal gland also held a fascination for me because it first becomes visible in the human fetus at forty-nine days after conception. This is also when the gender of the fetus is first clearly discernible. Forty-nine days, according to several Buddhist texts, is how long it takes the life force of one who has died to enter into its next incarnation. Perhaps the life-force of a human enters the fetus at forty-nine days through the pineal.

And it may leave the body, at death, through the pineal. This coming and going would be marked by the release of DMT by the pineal, mediating awareness of these awesome events.

In addition to the scientific puzzle presented by the similarities between psychedelic and mystical consciousness, there were issues of healing that also drew me to both. The sense of there being “something greater” resulting from major psychedelic episodes led me to think that psychedelics might be helpful to people with psychological, physical, or spiritual problems. It seemed crucial to avoid the narrowness that often spoiled claims for the drugs’ usefulness or dangers, and to hold a broad view. My emerging worldview resembled a tripod supported by biological (brain), psychoanalytic (individual psychology), and Eastern religious (consciousness and spirituality) legs. The first two legs were important in my decision to attend medical school. The third pushed me deeper into Buddhism.

Disheartened by the lack of spirit in medical training, I took a year’s leave of absence from medical school and explored Zen in a series of retreats. Zen’s emphasis on direct experience, its evenhanded approach to all mental phenomena encountered during meditation, and the importance of enlightenment all fit with my image of an ideal religious tradition. During my four-year psychiatric training, I helped found and run a meditation group affiliated with my long-standing Zen community. I was ordained as a lay Buddhist in the mid-1980s. This was the same year I trained in clinical psychopharmacology, learning to administer psychoactive drugs to human volunteers in controlled scientific studies.

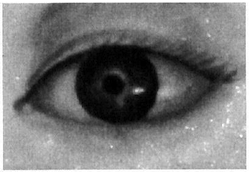

The form our research in New Mexico took was a traditional biomedical one, monitoring effects of several DMT doses on blood pressure, temperature, pupil size, and blood levels of several chemicals indicating brain function. We recruited experienced hallucinogen users who were psychologically and medically fit. This was because they would be better able to report on their experiences, and less likely to panic or suffer longer-lasting side effects, than drug-inexperienced volunteers. Volunteers believed in the ability of psychedelics to help “inner work,” and volunteered, at least in part, to use DMT for their personal growth.

The form our research in New Mexico took was a traditional biomedical one, monitoring effects of several DMT doses on blood pressure, temperature, pupil size, and blood levels of several chemicals indicating brain function. We recruited experienced hallucinogen users who were psychologically and medically fit. This was because they would be better able to report on their experiences, and less likely to panic or suffer longer-lasting side effects, than drug-inexperienced volunteers. Volunteers believed in the ability of psychedelics to help “inner work,” and volunteered, at least in part, to use DMT for their personal growth.

Was there a spiritual aspect to the DMT experience? And, if so, was this helpful in and of itself? This was one of my deeper reasons for developing our DMT research program.

Supervising sessions is called “sitting,” usually believed to come from “baby-sitting” people in a highly dependent and, at times, confused and vulnerable state. But, in our minds, Buddhist practice is as relevant a source for the term. Our research nurse and I did our best to practice meditation while with our volunteers: watching the breath, being alert, eyes open, ready to respond, keeping a bright attitude, and getting out of the way of the volunteer’s experience. This method is very similar to what Freud called “evenly suspended attention,” performed by a trained psychoanalyst who provided support by a mostly silent but present sitting by one’s side. I experienced this type of listening and watching as similar to Zen meditation.

Another example of how psychedelic and Buddhist meditation converged was in the development of a new questionnaire to measure states of consciousness. Previous questionnaires measuring psychedelic drug effects were not ideal for many reasons. Some assumed that psychedelics caused nothing but psychosis, and emphasized unpleasant experiences. Other scales were developed using volunteers, sometimes ex-narcotic-addict prisoners, who were not told what drugs they were given or what the effects might be. I had always liked the Buddhist view of the mind being divided into the five skandhas (“heaps,” “piles,” or “aggregates”) which, taken as a whole, give the impression of a personal self who experiences. These are the familiar “form,” “feeling,” “perception,” “consciousness,” and “volition.” I looked into several guides to the Abhidharma literature, the Buddhist “psychological canon” with over a thousand years of use monitoring progress in meditation. It seemed that a skandha-based rating scale could provide an excellent basis for a neutral, descriptive understanding of psychedelic states.

I let it be known I was interested in talking with people who had taken DMT. Soon, the phone was ringing with people wanting to describe their experiences. Most of the nineteen people were from New Mexico and the West Coast, and nearly all were involved in some therapeutic or religious discipline. They were well-educated, articulate, and impressed with DMT’s ability to open the door to highly unusual, nonmaterial states, which was greater than that of longer-lasting psychedelics like psilocybin or LSD. After completing these interviews, I decided to add a sixth “skandha” to the questionnaire, called “intensity,” which helped quantify the nature of the experience.

We gave and analyzed this new questionnaire, the Hallucinogenic Rating Scale (HRS), almost 400 times to more than fifty people over four years. It is interesting to note that the grouping of questions using theskandha method gave more sensitive results in our DMT work than did a large number of biological measurements, such as blood pressure, temperature, or levels of certain chemicals in the blood.

Besides informing our style of sitting for and measuring responses to drug sessions, Buddhism helped make sense of the experiences people had in our relatively sparse but supportive environment. For many volunteers, even those with prior DMT use, the first high dose of intravenous DMT was like a near-death state, which in turn has been strongly linked to beneficial mystical experiences. Several were convinced they were dead or dying. Many had encounters with deities, spirits, angels, unimaginable creatures, and the source of all existence. Nearly all lost contact with their bodies at some point. Elena’s case is a good example of an enlightenment experience—sounding identical to reports in the Buddhist meditative tradition—brought on by a high dose of DMT.

On one hand, a Buddhist perspective might hold all of these experiences to be equal. The matter-of-fact approach to nonmaterial realms in Buddhism provides firm footing for accepting and working with those experiences. It also does away with judging nonmaterial realms as better (or worse) than material ones—a tendency in some New Age religions. The experience of seeing and speaking to deva-like creatures in the DMT trance was just that: seeing and speaking with other beings. Not wiser, not less wise, and not more or less trustworthy than anyone or anything else.

On the other hand, how to meet head-on the volunteer who had a drug-induced enlightenment? Certify him or her as enlightened? Explain away by pharmacology the earth-shattering impact of the experience?

On the other hand, how to meet head-on the volunteer who had a drug-induced enlightenment? Certify him or her as enlightened? Explain away by pharmacology the earth-shattering impact of the experience?

It was confusing. At first, it seemed as if a big dose of DMT was indeed transformative. As time elapsed, though, and we followed our volunteers for months and years, my perspective radically changed. While some, like Elena, had profoundly beneficial results from her participation, a small number of volunteers had frightening, negative responses that required some care afterward. Other, more subtle adverse effects also crept in (as may happen with Buddhist practice) in the form of increased self-pride—that is, a division into those with and without “understanding.” In addition, “solving” problems while in an altered state—particularly common with high-dose psychedelic use—but then not putting the solution into practice, seemed to me worse than not even trying to work on the specific problem.

I have concluded that there is nothing inherent about psychedelics that has a beneficial effect, nor are they pharmacologically dangerous in and of themselves. The nature and results of the experience are determined by a complex combination of the drug’s pharmacology, the state of the volunteer at the time of drug administration, and the relationship between the individual and the physical and psychological environment: drug, set, and setting.

The volunteers who benefited most from their DMT sessions were those who probably would have gotten the most out of any “trip”—drug or otherwise. Those who benefited least were those who were the most novelty-saturated. The most difficult sessions took place in combinations of two factors, the first being an unwillingness to give up the internal dialogue and body-awareness; and the second being uncertain or confusing relationships between the volunteer and those in the room at the time. Therefore, the “religious,” “adverse,” or “banal” effects resulting from drug administration depended more upon the person and what he or she and those in the room brought to the session, than on any inherent characteristic of the drug itself.

Thus, the problem with depending on one or several transformative psychedelic experiences as a practice is that there is no framework that suitably deals with everyday life between drug sessions. The introduction of certain Amazonian hallucinogenic plant-using churches into the West, with their sets of ritual and moral codes, may provide a new model combining religious and psychedelic practice.

In the last year of our work, a more difficult personal interplay of Buddhism and psychedelics appeared. This involved what might be described as a turf-battle developing between my Zen community and me. For years, I had been given at least implicit support to pursue my research by several members of the Zen community. These were senior students with their own prior psychedelic experiences. In the last year, I described our work to psychedelic-naive members of the community, who strongly condemned it. Formerly sympathetic students appeared pressured to withdraw any support for my studies. This concern was specifically directed at two aspects of our research. One aspect was a planned psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy project with the terminally ill, research that demonstrated impressive potential in the 1960s. That is, in patients who were having difficulty with the dying process, a “dry run” with a high-dose psychedelic session might ease the anguish and despair associated with their terminal illness. The other area of concern was the potential for adverse effects, both the obvious and more subtle ones previously described.

Scriptural and perceptual bases for this disapproval were given, in addition to community members’ own and others’ experiences. However, it appeared to me that the major concern was that it would be highly detrimental for them, as a Buddhist community, to associate Buddhism with drug use in any way. It appeared that those students who had their own psychedelic experiences (and had found them to stimulate their interest in a meditative life) had to close ranks with those who did not.

What I have experienced as the friction between disciplines is not uncommon in the world at large, and perhaps within the Buddhist community in particular. That is, is it “Buddhist” to give, take, or otherwise occupy oneself with psychedelics as spiritual tools?

Several research projects are being planned across the U.S., using psychedelics to treat intractable drug abuse—a condition with a high mortality rate if untreated. I understand Buddhist precepts to condone the use of “intoxicants” for medical purposes (e.g., cocaine for local anesthesia, narcotics for pain control). Whether or not a Buddhist who gives or takes a psychedelic “intoxicant” for the treatment of a medical condition faces similar criticism will be important to note. Complicating this case is the point that the psychological/spiritual effects of a properly prepared and supervised psychedelic session might be seen as curative.

Several research projects are being planned across the U.S., using psychedelics to treat intractable drug abuse—a condition with a high mortality rate if untreated. I understand Buddhist precepts to condone the use of “intoxicants” for medical purposes (e.g., cocaine for local anesthesia, narcotics for pain control). Whether or not a Buddhist who gives or takes a psychedelic “intoxicant” for the treatment of a medical condition faces similar criticism will be important to note. Complicating this case is the point that the psychological/spiritual effects of a properly prepared and supervised psychedelic session might be seen as curative.

In a final area of possible overlap, I believe there are ways in which Buddhism and the psychedelic community might benefit from an open, frank exchange of ideas, practices, and ethics. For the psychedelic community, the ethical, disciplined structuring of life, experience, and relationship provided by thousands of years of Buddhist communal tradition has much to offer.

This well-developed tradition could infuse meaning and consistency into isolated, disjointed, and poorly integrated psychedelic experiences. The wisdom of the psychedelic experience, without the accompanying and necessary love and compassion cultivated in a daily practice, may otherwise be frittered away in an excess of narcissism and self-indulgence. Although this is also possible within a Buddhist meditative tradition, it is less likely with the checks and balances in place within a dynamic community of practitioners.

However, dedicated Buddhist practitioners with little success in their meditation, but well along in moral and intellectual development, might benefit from a carefully timed, prepared, supervised, and followedup psychedelic session to accelerate their practice. Psychedelics, if anything, provide a view that—to one so inclined—can inspire the long hard work required to make that view a living reality.