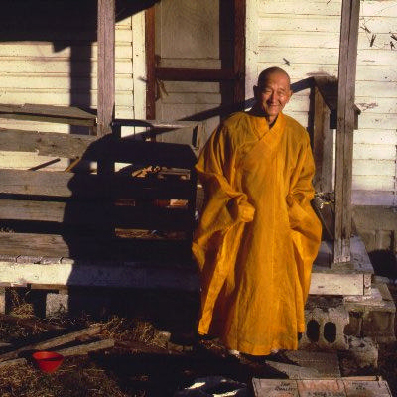

If anyone in Monteagle, Tennessee, took notice of a “Chinaman” walking down the street in 1965, dressed like a coolie, they would have dismissed the implausibility with one of two explanations: He worked as a cook at the Holiday Inn, or maybe he owned the shirt laundry in Tullahoma. Ta Tsung was in fact a Ch’an Buddhist monk who, in his endeavor to live apart, bought a cottage in Monteagle with the intention of meditating, painting, and growing vegetables.

The last time I saw Ta Tsung was in 1983, at a little temple in San Jose where he was staying with an old friend before returning to Hawaii to retire. A decade passed before I began to look for him again. When I would tell Ta Tsung stories to friends, inevitably they would ask, “Where is he now? Is he still living?” I could only shrug and say that I had no idea. It seemed strange to them that I had lost track of him. But all of his acquaintances, in fact, lost track of him.

For the historical record, I can tell what few facts I have been able to verify about his life. He was born in Shanghai, China, in 1907, and died in San Jose, California, in 1986 (of pneumonia and complications from a head injury sustained in a fall). After World War II he kept an orchard of many varieties of fruit trees in Zhejiang Province, near Ningbo. When this was nationalized, he headed for Hong Kong, where he worked as an accountant in a government-owned department store. In his forties, he took monastic vows. These would have been familiar to him, as he had been raised from the age of eleven in a monastery. His master was the venerable Ming Kuan. In a recent conversation with a monk in the same lineage, I heard him referred to for the first time as Dharma Master Ta Tsung. I wasn’t surprised. Those of us who knew him had expected as much. He emigrated to the United States in 1960, serving in temples in Hawaii and New York, and moved to Monteagle in 1965, just a few miles away from Sewanee, known more formally as the University of the South.

As one Sewanee alumnus put it, “At that time, the campus was buzzing with meditative energy—the fellows who lived on my hall were all meditating, or eating magic mushrooms and talking to trees. And so maybe it was inevitable that we sniffed him out.” In any event, the university students probably provided a kind of buffer with the community of Monteagle. It was plausible that Ta Tsung bore some connection, albeit distant, to the university—a sort of adjunct professor on the down-and-out. But there must have been more to it than that because by the time I met him in 1977, the local folk already held great affection for Ta Tsung. An episode recounted by former Sewanee student Gene Ham may explain why.

As one Sewanee alumnus put it, “At that time, the campus was buzzing with meditative energy—the fellows who lived on my hall were all meditating, or eating magic mushrooms and talking to trees. And so maybe it was inevitable that we sniffed him out.” In any event, the university students probably provided a kind of buffer with the community of Monteagle. It was plausible that Ta Tsung bore some connection, albeit distant, to the university—a sort of adjunct professor on the down-and-out. But there must have been more to it than that because by the time I met him in 1977, the local folk already held great affection for Ta Tsung. An episode recounted by former Sewanee student Gene Ham may explain why.

When one of the neighbors told him that he ought to cut down the dead oak in front of his house (unless he wanted it indoors with him), Ta Tsung promptly went to the same thrift store where he bought all of his clothes, purchased a hatchet for a few pennies, and set about cutting down this tree of enormous girth.

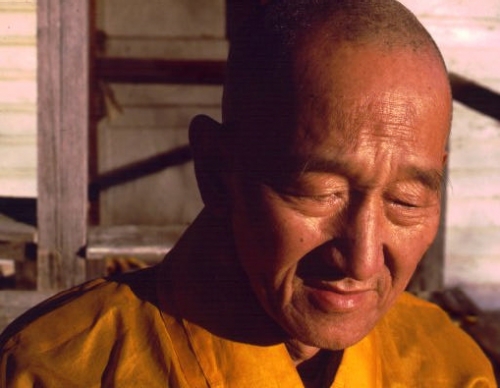

Each morning when his windup alarm clock sounded, he’d pull the chain that turned on a single sixty-watt bulb, sit upright, pull one foot onto the opposite thigh, and meditate. Years of lighting incense in the temple, of catering to men and women who made offerings so that their businesses would prosper, had inspired him finally to reduce his practice to the essentials—meditation, followed by tea and breakfast, followed by a morning of hacking away at the enormous tree in his front yard with a hatchet.

It didn’t take very long for Ta Tsung’s early morning activities to arouse the curiosity of his neighbors. Soon they arrived with chainsaws, freshly sharpened and primed with gasoline, but Ta Tsung just shook his head and said, no, he had to do it that way. They chuckled at this peculiar old fellow who insisted on making things difficult for himself. But they developed a grudging respect for his persistence, his solid regularity. He became, quite literally, a part of the neighborhood. If he missed a morning of hacking at the tree because of an appointment elsewhere, he was missed.

Ta Tsung had weeks to plan where the tree would fall. Gene arrived late one morning just as he was getting ready to make the last few cuts. He watched the little old man swing the hatchet against the tree until finally it began to fall. Slowly at first, then with increasing speed, it cracked and groaned and crashed to the ground, bouncing several times and shaking every house on Spring Street.

“So, Ta Tsung,” Gene asked. “What are you going to do with your mornings now?”

“Make firewood,” he replied.

And so he did. In a few months, he had the whole tree neatly cut and stacked behind his little house. During this time, one of the university students must have made it known that Ta Tsung was a Buddhist priest. I’m not sure whether the fact of his ordination really meant anything to them, or whether it was that they respected his determination with the tree—but from that time on, he became known to the local people as “Reverend Ta Tsung.”

Ta Tsung never tired of talking about the merits of organic gardening. “No chemical!” was his mantra, his dogma, and his precept. He could become tiresome on the subject if allowed to run his course, but I later came to see that there was more to his culinary philosophy than mere obstinance. Apparently he had been very ill when he moved to Tennessee. Perhaps in the effort to convert him, his neighbors, who were Seventh-Day Adventists, put him on a strict dietary regime, which eventually cured him. Years later, when he had moved to California, I took him to a Seventh-Day Adventist restaurant where the food was to his liking. “Seventh-Day Adventists,” he muttered. “Crazy kind of Christian.” But he respected their attitude about food, which in Ta Tsung’s world was about as important as anything.

One day, Steve, Clark, and I (the three of us from Sewanee who knew him) took a walk through Abbo’s Alley, a kind of informal botanical garden that runs the length of the campus proper. As we approached a house whose backyard abutted the Alley, we came upon some big, bright pumpkins. Ta Tsung turned around and said, “You come Saturday. I make pumpkin pie for you!” We accepted without hesitation, though I did wonder what he meant by “pumpkin pie.” I expected it would not be like anything we had ever seen.

One day, Steve, Clark, and I (the three of us from Sewanee who knew him) took a walk through Abbo’s Alley, a kind of informal botanical garden that runs the length of the campus proper. As we approached a house whose backyard abutted the Alley, we came upon some big, bright pumpkins. Ta Tsung turned around and said, “You come Saturday. I make pumpkin pie for you!” We accepted without hesitation, though I did wonder what he meant by “pumpkin pie.” I expected it would not be like anything we had ever seen.

When Saturday arrived, we piled into my car and drove to Monteagle. As I had guessed, there was no pie—no crust, no eggs, no sugar. In fact, there was no pumpkin. He had confected a dish of sweet potatoes and oatmeal, into which he had added a little whole wheat flour as a thickener, and topped it off with some organic peanut butter. It was cooked rather soft, since he didn’t like wearing his teeth, but it tasted wonderful.

When we’d finished, Steve volunteered to wash up. He tended to everything, from the dirty pots to the delicate china bowls. Somehow, even doing ordinary chores at Ta Tsung’s house became an opportunity for the practice of mindfulness, and Steve took to the job with earnest enthusiasm.

The spoons we had eaten with were of the plastic picnic variety and had seen much use but, like so many other things in the old Chinaman’s house, had been saved for reuse from some ancient time past. While Steve was handling one of these spoons, it ceased to be a spoon—that is, it broke. This became a miraculous koan.

At first Steve was mortified, as if he had destroyed a priceless treasure. He looked around for a trash receptacle in which to discard the spoonless plastic before he was discovered holding it. There wasn’t one outside, so he looked in one room, then the other, and came to the conclusion that while Ta Tsung had a compost pile for food scraps and his own excrement, and scraps of paper and wood were used for fuel, he seemed not to have a garbage bin. There was no category of things designated as “to be thrown away,” and no such place as “away” for them to be thrown.

Looking back on it now, I find it extraordinary that Ta Tsung managed to remain almost completely unknown. With all the spiritual turmoil of the Vietnam War and its aftermath, surely he could have attracted a following. But then, he would not have been who he was. Another story, circa 1968, as told by Gene:

Carson and Steve and I had discovered Ta Tsung independently, but we were soon traveling“en famille”to go get wisdom from him. Some of us—Henry and Carson, I believe—had already started to learn meditation from an itinerant guru named Adano Ley. Adano traveled the South in an aqua and magenta jumpsuit and had some kind of connection with Yogananda’s Self-Realization Fellowship, though the nature of this connection wasn’t entirely clear. Adano hinted that all sorts of magical miracles followed him about, and this was really impressive to those of us who were nineteen.

Someone decided that it would be just great if we took Ta Tsung along to meet this jumpsuit-clad guru. We told him that there was a free vegetarian dinner and some kind of ceremony following. So Chip Burson made the rounds picking us up, wives and girlfriends and Ta Tsung all crammed in the back of his Willys’s bread truck, and we trundled down the mountain to Manchester.

The dinner was uneventful. Ta Tsung nodded politely whenever someone asked him what he thought about the evening, always taking a bite of food when asked about Adano Ley. At some point in the evening, apples and aluminum foil were passed out. Each person in attendance wrapped their apple in the foil, and Adano Ley conducted a guided meditation, the purpose of which as I understand it was to direct the bad karma of each person into his or her apple. The apple was to be placed on a shelf for a week or so, and only then examined. A really rotten apple must have meant a lot of bad karma, or an effective meditation, or something like that.

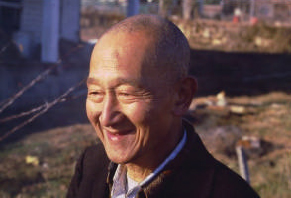

The trip back up the mountain had everyone in inspired silence, a continuation of the impressive experience of earlier that evening, until a rude “CRUNCH!” from the back of the truck broke the silence. I looked at Ta Tsung, who was grinning like an idiot, a large chunk of apple held between his dentures. Not being one to waste anything, he folded the tinfoil into his sleeve and continued eating. Without even a second thought, I unwrapped my apple, gave the foil to Ta Tsung, and started eating mine, too.

As Carson Graves said later, “In any case, this was the beginning of the end of our interest in gurus, and also served to increase our respect for Ta Tsung, who never made any claims for himself whatsoever.”

So who was Ta Tsung? And what was he doing all those years in rural Tennessee? A story Gene tells is likely to be as good an answer as we’re going to get:

One day in early May, I was driving down the street in Monteagle when I spied Ta Tsung sitting on the stone wall under a big oak tree in front of the Methodist Church. He had a small easel and his ink brushes and other paraphernalia, and I guessed that he was painting from life.

It turned out that it was only another one of his Chinese landscapes, with great mountains, cataracts, and flowing streams. About two-thirds of the way down from the top was a small clearing in a pine forest where a hermit, diminutive in the grandeur of the landscape, was sweeping his hut. He had a smile on his face and a glow about his head.

“What’s that about?” I asked Ta Tsung.

“This person just have enlightenment sweeping hut.”

“What happens next?”

“Keep sweeping.”

Author’s Note: For many years I struggled with holding up Ta Tsung as an example—wanting to share my experience with others, but knowing with a fierce certainty that he would have offered a curt dismissal to anyone seeking to emulate him. As I matured, in my practice and in my life, I began to see that Ta Tsung is simply an example of an individuated life, of someone who became himself.

This is the lifelong work that follows a profound experience of insight. While we students of Zen sometimes talk about kensho, or satori, as some kind of ultimate experience, it is nothing more or less than opening the gate to the garden. – Michael Sierchio