From the thin, rocky ridge where a few friends and I were resting following a 13,000-foot climb, we could look out over the entire expanse of New Mexico’s Pecos Wilderness, east over the Great Plains, and north as far as Colorado, almost 200 miles away. As we sat there in a circle, sheltering each other from the strong mountain winds, we silently passed around a water bottle full of fresh peyote tea. We gulped down the bitter mixture and then lit tobacco and sage as an offering to the local spirits. As the peyote began to take effect, we took turns praying aloud for what we hoped to take from the experience.

That was six years ago, and I was nineteen at the time, but I first started using psychedelics when I was fourteen years old. I was raised at the Rochester Zen Center; my parents were on resident staff there for the first fourteen years of my life. The Zen Center, like most monastic-style Buddhist communities in America, discouraged the use of alcohol or drugs, or any substances that “clouded the mind.” There seemed to be the attitude among staff members that they had finished their reckless days of experimentation and indulgence in makyo (hallucinations), and graduated to more serious practice. Having taken the Buddhist precepts at age seven, I also had mixed feelings about drugs and experimentation.

So while on the one hand I was coming from a place that definitely saw the use of drugs as a juvenile indulgence, on the other hand I was just entering my teenage years and wanted to test the bounds of reality a little bit. I “converted” to Tibetan Buddhism, which I have practiced with some degree of leisure ever since.

Fundamentally, I saw the use of psychedelics as a process of self-inquiry, which seemed to be entirely in keeping with Buddhist thought. Testing the bounds of reality, asking “What is the nature of mind?”, seeing the impermanence in all phenomena, and having one’s sense of self challenged seemed to be not only elements of the psychedelic experience but also basic tenets of Buddhist practice. So while there was something of a moral question when I began dropping acid, there was never the idea that what I was doing was in any way out of sync with my basic Buddhist philosophy.

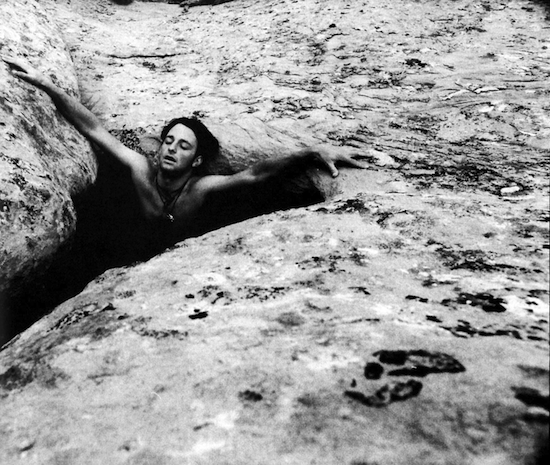

Having been raised a Buddhist, the lotus lands and deva realms I saw on acid were not new phenomena, but felt quite familiar. Spending my adolescence juiced on mushrooms and peyote, and running through the thick pine forests of northern New Mexico howling at the moon, I didn’t feel as if I was experiencing anything drastically new on acid. It seemed like more of an extension of my Buddhist childhood. I saw collapsing landscapes breathing and melting into one another, and I thought: impermanence! All connection to words, thoughts, and the intellect shattered, and I knew the experience of selflessness.

For a while during my adolescence, psychedelics seemed to be my only way of relating to a society that, because of my upbringing, I had always viewed as foreign and bizarre. Not coincidentally, I began dropping acid the same year my parents left Zen Center. When we suddenly found ourselves plopped down in the middle of American society, psychedelics became a way to recreate my lost childhood experience. Whereas other sectors of society seemed impenetrably foreign to my Buddhist sensibilities, I understood the principles and the philosophies of the psychedelic world, so it didn’t seem all that alien. The drug subculture was the only part of American society I could really relate to.

I have probably dropped acid about forty times. Although I had a number of experiences that I would definitely classify as comical, I really never had a bad experience. In retrospect, I believe my Buddhist upbringing gave me a framework for my psychedelic experiences. People who have bad trips get stuck in a fragmented mind-state and are convinced that it will last forever. But I never felt in danger of “going over the edge” or “freaking out.” No matter how bizarre or otherworldly my experiences became, I always felt a centeredness and certainty that this fragmented mind-state, too, was impermanent. In the swirling world of psychedelic madness, I always felt connected, almost by a tangible cord, to a wellspring of clarity and sanity.

What contributed to making my psychedelic experiences so valuable was the fact that there was almost always a sacred context. My friends and I would have ceremonies when we tripped. We would pray, meditate, and remain outdoors in natural settings, never “dropping” in the city.

Taken purely for recreation, psychedelics can be very dangerous. But with the proper context and support, they can provide the user with a concrete, physical experience that relates to many of the philosophical abstractions of Buddhism—as in all things: the middle way.

So as I sat there on the mountaintop, I thought of the buddhas and bodhisattvas, and visualized myself standing before Amitabha Buddha, shining brilliant red, surrounded by a vast retinue of deities, floating radiantly on lotus-borne clouds. In the clear blue sky above, with its impossibly white puffs of cloud, and with the peyote juice rampant in my veins, the visualization leapt to life.

I offered up the whole universe to that gathering of deities: the endless pine forests, the granite peaks, the clear mountain rivers, the noisy flocks of birds, and the golden herds of elk-all present there, as my offering mandala.

I asked for guidance in my life, for clarity on my path and for a better understanding of my own true nature. I asked that I might use the lessons of that afternoon to better help all sentient beings be free of suffering. And I thanked that splendid gathering for all the gifts I had received throughout my life. Then, in keeping with the basics of Tibetan visualization practice, I allowed the image to dissolve, to be scattered across the world by the clear mountain wind. I visualized the light of those buddhas and bodhisattvas spreading far from that mountain peak and touching all sentient beings. I knew in that moment that this life is as intangible as a wisp of mountain cloud.