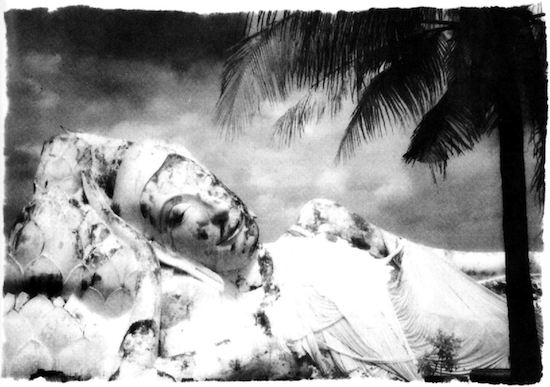

With more than a little trepidation, my girlfriend Marion and I boarded a flight to Hawaii. Once buckled in, I fell into a deep and unusually restful sleep. Hours later, I raised the shade and, overcoming a blast of near-blinding light, peered out the small window. The palm-fringed handful of islands strewn in a random arc in the middle of the blue Pacific looked like the last grains from a weary sower’s hand. I remembered that it wasn’t for the black sand beaches and helicopter rides over volcanoes that I had made this journey. It was 1987, and my moment with a shaman was coming near. I had an appointment with yagé,the “vine of the soul.”

Walls of red sugarcane stalks lined the highway from the airport as we sped to the place of my appointment: a botanical reserve amidst climax rainforest on the slopes of the Mauna Loa volcano. The placid blue ocean stayed constant, while the scenery on the other side of the road turned dryer, harder, and darker, and the mileposts whizzed by. Finally, the land was just a solid black crust of once-liquid lava beds as far as the eye could see, resembling a black version of a lunar landscape. A volcanic haze called “vog” hung high in the horizon above the still-fiery Pele some twenty miles farther to the south.

We turned up an inland road, parked, and boarded a waiting jeep. As we climbed the bumpy road, we noticed hints of vegetation appearing here and there, leading to persimmon bushes, and then groves of ginger flowers, mango trees, and macadamia trees. As we entered the reserve area we found ourselves on the edge of a jungle, an overgrown thicket of kukui grass with spectacular ocean views peering between tall trunks of blossoming ohia trees.

The shaman, with a gray beard and wizened features, greeted us with some Kona coffee and showed us to our quarters. The appointed hour was drawing near, and after a short rest, we assembled on the porch to drink the yagé—a catalyst for perhaps the most powerful and intensely visionary experiences ever known.

The sun was setting over the jungle as I contemplated my glass of the pungent brew. An incredible amount of work went into producing this thick, dark chocolate-like drink. Yagé is brewed from the Banistereopsis caapi vine mixed with the leaves of the DMT-rich Psychotria viridis, plants that originate from the Amazon rainforest, but also thrive in Hawaii. They are boiled first separately and then together for over a week, requiring constant stirring and removal of pulp. The origin of the recipe is itself a mystery, and I wondered what the odds were on the Amazon Indians discovering this formula randomly through trial and error.

I had read the descriptions of encounters with yagé by contemporary Westerners in William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg’s The Yagé Letters, the McKenna brothers’ The Invisible Landscape, and Andrew Weil’s The Marriage of the Sun and the Moon. Nothing, however, except perhaps Buddhist meditation practice, had prepared me for what followed after emptying my glass.

I kissed Marion goodbye and was shown to the tent that the shaman had set up for me farther into the jungle. He wished me luck, reminded me not to cling to any visions, delightful or horrifying, and disappeared into the night. The stars above were so bright and numerous that I couldn’t take my eyes off the night sky. I remembered a bit of unfinished business to do before losing motor control, and picked a spot in the ground in which to deposit my vomit when it came time. Still feeling normal, my gaze returned to the starry heavens.

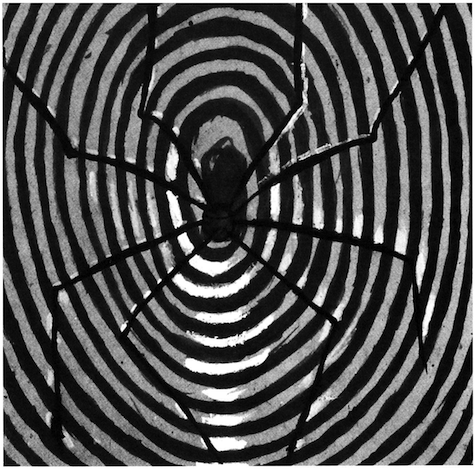

I was expecting all hell to break loose any second, but what ensued was so subtle that I could hardly believe it was a function of the vine. As I stared at the star formations, I could suddenly see that these were not isolated stars but points of light on a giant body – the body of a massive spider. She moved her body ever so subtly, as if to offer confirming evidence of her existence. When the spider moved, all the sky moved in relation to her, and in scale the way the many legs of a real spider would actually move.

This didn’t feel like a hallucination at all, but more like a filter had been removed, and I was suddenly able to see the true nature of the sky. I was ecstatic, not from the drug, but from the honor and thrill of seeing the heavens in all of its true form, power, and beauty. My preoccupation with the animated, breathing sky above me was interrupted by a powerful feeling of being lifted off the ground. The next thing I knew I was staring closely at the dirt and hearing a torrent of matter fleeing my body, its stream forming one leg of a tripod, my hands the other two, as my legs flailed about straight up in the air. The sound of my wretching reverberated through the jungle like a call to the spirits for help. I had expected the vomit, but what mystified me was how I was being supported upside down as it gushed from my mouth.

The feeling of being drugged was definitely kicking in now, and I quickly found my way into the tent and lay down. Just before I was able to get horizontal, a light and color show began. I laid back and watched the most extraordinary colors vibrate and gyrate into fractals. The colors were unlike any I had ever seen, and they displayed themselves with the most remarkable intensity. They seemed unaffected by whether my eyes were open or closed, and the first feeling of fear set in. Was I blind? Would I ever see the real world again?

Growing tired of the swirling colors, I longed to see my raised hand or the inside of the tent. How could I have done this to myself? I kept wondering. Please let it be over, I prayed. But the journey had just begun, and the light show was the fun part. I struggled to turn my mind away from the compelling visions to the steady rhythm of my breath. Suddenly the sound of my breathing became almost ear-shatteringly loud, as if it was blowing across the surface of a distant planet, like a giant windstorm.

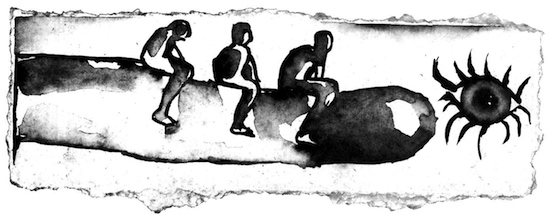

Then my body vanished, and only my mind and sensory impressions remained. Gradually the true meaning of this experience became clear—I was journeying to the end of my life. In the process, I came to grips with something I had no idea was true about myself—that I was completely unwilling to believe that death was real. Intellectually, I was aware, like everyone else, of the inevitability of death. But the reality of the very moment of death, the moment of my last breath, was not something I was willing to see. And then I saw it. I was back on Earth, standing in the mud outside my tent and staring disbelievingly at a corpse—my own. I picked up a hand and felt the cold weight of an arm that would never again move on its own, and dropped it back into the mud. I noticed a small trail of blood from its mouth across an unshaven and pale cheek dripping into the mud. All the while I heard my mind saying, “No, it’s not real, it’s just the drug,” but my eyes saw my lifeless body laying there, real as could be.

As if this wasn’t convincing enough for my persistent ego, I flashed on a scene in which I was driving by a cemetery, only to notice one tombstone standing out among the others. I read with total horror my own name chiseled across the tall granite slab. Images from my life flickered before me, first slowly, then in hyperspeed, and finally there was just blackness. Death was finally real and surrender was the only option. But why didn’t this voice I was hearing stop, and who, or what, was listening to it?

I didn’t have much chance to reflect on these important questions before finding myself back in another struggle to survive. This time I was noticing the scenery had changed. It was more fantastical, more dark, more frightening. Dead as I was, I still found myself on the run, this time from a classic fire-breathing dragon. I almost laughed at the clichéd imagery when the surroundings grew increasingly more macabre. The world became a series of caves, populated by bizarre forms of life. Mechanical and yet biological, these machinelike beings twisted and turned in mathematical precision with each other as if I were peering into some nanotechnological microcosm of the dark forces of nature. A strange haunting melody accompanied their gyrations. Whenever I found myself fascinated with some aspect of what was undoubtedly the underworld, a blast of fire from the dragon curled around me and singed the hair on my legs. The verisimilitude of this vision and the smell of burning hair had me biting my lip so hard I could taste the blood.

Suddenly I unsheathed a giant sword and stabbed the beast repeatedly in every part of its scaly body while narrowly avoiding being burned or swallowed. I thrust the final blow to the throat and watched the torrent of blood pour from his wound until the thrashing of its long powerful tail finally ceased. As I stared into the closing eyes of the now slumped dragon, I could see a glimmer of recognition. Slipping out of consciousness, its face slowly metamorphosed into a more human one, and gradually it became clear that the face the dragon was wearing was my own.

I stared at the dead dragon and felt a tremendous upwelling of sympathy and compassion. As a tear slid down my virtual cheek, I reflected on what a fantastic lesson in self-as-other this experience was: here was a despicable, horrible beast intent on crushing me between its teeth or burning me to a crisp, yet I was able to widen my circle of compassion to embrace it. What enemy could I have, what unspeakably vicious act could I not forgive after this? The lesson was swift and immediate.

Then, for what seemed to be an eternity, I experienced a complete and total void of any sensory input. There was no time, no place, no visions, no sounds, no feelings. Even my thoughts, which had been intact throughout the ordeal, seemed less forthcoming and harder to grasp. I tried to muster enough mental energy to form at least the desire for life. Something in my essence was pleading for life, some kernel of consciousness was intent on seeking an animated state. Muscles and nerves seemed to create themselves anew, attempting to generate at least a tingle of sensation.

Perception of my surroundings—the dull gray color of the tent and the moon shadows dancing on its surface—crept into my field of vision so gradually I hardly noticed they had been absent. The world I had just visited still felt very much present, separated from me by no more than the flimsiest of veils. My thoughts returned, and the first one was gratitude. The sensation of being distinct from the mud, of having a community of bones and sinews with which to feel the damp canvas floor against my back was quietly thrilling. To see the play of light and dark along the tent walls and hear the throaty call of nearby insects was indescribably joyful. Slowly I raised my tired body and stepped out into the night, inhaling what felt like something very alive itself—the sweet and perfumed night air. I was grinning so hard I thought the corners of my lips might crack. I sank to my knees and practically buried my face in the mud, examining closely the surface of the earth and tasting with the tip of my tongue the richness of her soil. My thoughts turned to Marion, and how delicious it would be to hold her and to be held. I stumbled along the roots of vines and carelessly brushed passed the blades of the bush to find my way back to the main house.

Immediately after coming through the door I confronted the shaman, who was busy stirring a large pot of the foul-smelling brew. “How could you do that to me?” I asked. The shaman stopped stirring, brought me some water, and sat down at the table with me. “Did you suffer?” he asked. Although I felt as though I had never in my life suffered so intensely as in the last few hours, at that moment I was aware of much greater space in my mind around the very notion of suffering itself. Buddhism teaches us that suffering is an inevitable part of life, but to have experienced so concentrated an episode of mental torture was like bringing the teaching into my cells and making it an organic truth of my life.

Although suffering exists, I deeply understood for the first time that no sufferer really exists. Throughout my journey I was actively doing and thinking, but having confronted the truth of my demise over and over, it was painfully obvious that I had no actual inherent existence. I was astonished that as he asked me the question, I no longer seemed to have any aversion or charge about suffering itself. As a graduate of the journey, I demonstrated my willingness to suffer and die. I reflected on the words of a gentle Buddhist monk from Sri Lanka now living in Brooklyn: “People are at their cruelest when they are intent on avoiding suffering.” So in response to the shaman’s query, I found myself smiling and I uttered simply, “Yes, but I recognized the emptiness of it.”

As I looked into the shaman’s eyes I found myself staring into the face of a dead man. It felt miraculous that we were animated, breathing, and making sounds. I looked at my hand for a few moments, and it seemed like a stranger’s hand—belonging more to my parents and my ancestors than to me. My eyes shifted to the flame under the pot, and then they narrowed and closed. The shaman and I spontaneously began to meditate, sitting totally still and silent for at least fifteen minutes. I have observed that my meditation practice jumped to a new level since the journey, and I find it easier to stay concentrated on my breath. Perhaps the reason for this is simply that the breath itself is more interesting to me, and I remain amazed that we have this capacity to exchange gases in the invisible soup of life within which we live and move.

The most powerful and obvious transformation resulting from this appointment with the shaman was in my relationship to death. I was dramatically aware of how diminished my fear of it was, and that not only could I hold thoughts of death while remaining in a pleasant state of mind, I was actively looking at death and the reality of dying for inspiration, clarity and a deeper context for my life. Beyond my new respect for death, the nature of my relationship to Buddhism also felt very different. Whereas Buddhism used to seem more like a vehicle with which I was seeking a destination, it now seems like a clever way to enjoy the present moment and little more. I’m not sure I have any hopes for ultimate realization, but I do have a stronger interest in spending more of my life in Buddhist practice.

The shaman asked me if I would consider taking the yagé again. I had to laugh. A chuckle turned into bellows of belly laughs followed by sharp cries of uncontrollable laughter. The notion of taking the vine or any other psychedelics again seemed absolutely preposterous. “No way, José,” I replied. The morning sun would soon be upon us, and I thought of how its light would allow me to see the multitude of flowering plants in the area. I thought of how psychedelic it would be just to see the flowers and bring them to my nose. Suddenly the prospect of having a baby seemed far more exciting than dropping a neurochemical bomb in my system to see endless parades of colors and forms.

“You had a good journey,” the shaman said as we left the table and prepared to take a nap before the dawn. “Why?” I asked, “’That which does not kill you makes you stronger,’ as the saying goes?” “No,” the shaman replied with the most lively grin I had seen on his face so far, “that which kills you makes you stronger.”