I ARRIVED TOO LATE on the last night of the Kagyu Monlam to receive one of the battery-operated candles that glowed like an old-fashioned Christmas bulb, turned on and off with a twirl of the faux brass base. Thousands of them had been somewhat miraculously obtained and distributed by the Chinese groups who sponsored this year’s Kagyu Monlam, one of many traditional Tibetan Buddhist prayer festivals held each winter in Bodh Gaya. Ever since the Mahabodhi Temple Management Committee outlawed the use of real candles (both butter and wax) throughout most of the temple complex that commemorates the historical Buddha’s enlightenment, the matter of light offerings has demanded some innovative approaches. While I was stuck waiting for a plate of chow mein at a nearby Tibetan tent restaurant, red and gold plastic candles were methodically doled out, with a kind of organization notably new to the often chaotic entrance to the stupa. By the time I made it back to the site, night had fallen, the full moon was holding itself steady and low in the eastern sky, and the crowd of over five thousand monks and nuns were holding their non-dripping, non-smoking, flameless candles overhead.

One week before, I’d stumbled out onto the platform at the Gaya railway station, twelve kilometers away, at five in the morning, indecisive about whether to risk the predawn ride to Bodh Gaya or to wait the hour and a half until daybreak. Ever since Hsan-tsang was robbed on the road from Gaya in the seventh century, pilgrims have been rightfully wary of this road in the dark. By ten minutes after five, though, I was too antsy to wait. As the auto rickshaw twisted through the empty darkness of Gaya, what struck me was not my preoccupation with the real or imagined danger of being robbed, but the almost comforting familiarity of it. Six years had passed since my last visit to Bodh Gaya, and in the interim all I’d been hearing about was how much everything had changed—how, people said with disdain, it had become so commercial, touristy, built-up. But upon arrival—at least in the dark and from several kilometers out, on terrible roads and with the driver smoking a bidi and his dashboard Hindu gods blinking away—everything seemed exactly, horribly, wonderfully the same.

Though cultural clashes and economic disparity are common throughout a rapidly modernizing India, Bodh Gaya, where the Buddha became enlightened twenty-six hundred years ago, is a particularly unique illustration of twenty-first-century juxtapositions. Because donating money to temples is considered good karma for Buddhists worldwide, and international travel is easier than ever, what was not very long ago the tiny town of Bodh Gaya is now home to unforeseen wealth, construction, and traffic. Meanwhile, the state of Bihar, where Bodh Gaya is situated, remains the poorest in the country, with disproportionately high rates of illiteracy and corruption. With an estimated year-round population of only twenty to thirty thousand (almost exclusively Hindu and Muslim), the permanent residents of Bodh Gaya rely and even thrive on the business of pilgrimage. At times, perhaps inevitably, they also struggle to sustain themselves in the face of it. Also, as Bodh Gaya expands and its appeal widens, Buddhist practitioners of all stripes are struggling to find the isolation and retreat they had hoped for. What’s most interesting in this overlap—between the day-to-day of a local population trying to support itself and the visiting Buddhists from the world over—is what they share and how they maintain a sense of symbiosis as everyone is pushed forward together into the future.

JAMAL KALU, a middle-aged Sunni Muslim with square glasses and well-spaced teeth, is a tailor, the very picture of a successful local businessman subsisting on the religious activity that makes Bodh Gaya tick. During the last week of December, he had orders for eight sets of Tibetan robes and sixteen sets of Korean ones, along with both Western- and Indian-style shirts. In early fall, he is often found making traditional Indian clothing such as salwaar kameez and kurta pyjama for new arrivals; in November, he begins measuring Tibetan women for chubas, or traditional Tibetan dresses; in March, he is sewing Hindu wedding clothes for spring.

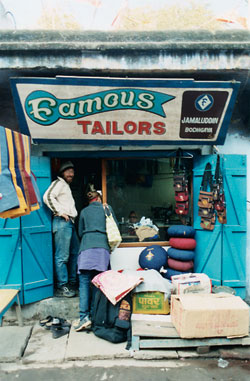

The father of seven sons and one daughter, Jamal was born and raised in Bodh Gaya. His father was also a tailor, and his grandfather made homespun cloth, khadi, on a loom, like Gandhi did. Jamal and his brother opened his shop, Famous Tailors, in the seventies, and he has done well, if modestly so, for himself and his family. Likewise, his eldest son has opened Famous Button—selling stationery and notebooks as well as buttons—behind a row of fruit sellers just east of the stupa entrance. Famous Tailors, which is exactly big enough for three pedal-operated sewing machines and one cabinet, is just a bit farther down, on the left side of the back road to Gaya.

Overall, Jamal seems content with his business and with Bodh Gaya. His children have all been well educated, and he is now a grandfather. As we sat having tea one evening, the horns, bicycle bells, cows, and dinnertime bustle outside his shop provided a comforting backdrop. Jamal said that for him, the biggest change in Bodh Gaya can be measured by the surplus of new hotels, which have been sprouting like mushrooms on the far side of town, heading westward from the stupa. When I asked if he felt that Bodh Gaya was safer than before, he was quick to point out proudly that Bodh Gaya has always been safe and that people of different religions and classes have always been “okay” here, even though, as he said, Gaya and the rest of Bihar remain crime-ridden.

While the geography is shifting with the construction of new temples and new roads, Bodh Gaya’s basic layout remains L-shaped, with the Mahabodhi Temple at the corner of it (though about ten years ago, the road was slightly rerouted to keep traffic from passing directly in front). The top of the “L” heads out to most of the other temples in town, including, most famously, the gold gilt Thai temple, the big Japanese Buddha, the Root Institute meditation center, the Bhutanese temple, and all of the newer, bigger hotels. Famous Tailors, the post office, two hardware stores and several mattress makers are situated along the bottom of the L, which runs parallel to the Falgu riverbed.

Farther down that same road, business hasn’t been as good. Across from the Burmese Vihar sit three restaurants—two named Pole Pole—that have not done as well recently as they did in the nineties. Shiva Nanda, the owner of the white Pole Pole, plays the drum alone most nights in his restaurant, which used to be filled during the winter months with Western Buddhists playing Scrabble. This drop in business can be attributed in part to the fact that many of the Tibetan tent restaurants, open for only a few months out of the year, offer a more expansive menu than the finger chips, eggs, and fried rice of the Pole Poles. But Shiva Nanda, who is tall, mustachioed, and Hindu, also knows that being on this side of town was sort of the geographic luck of the draw and that there’s not much he can do as the other side continues to expand.

The current temple count, including those in the process of being constructed, stands at forty. Inspiring proof of a flourishing, global sangha, such numbers have also made their mark on the local real estate market, and land prices have skyrocketed. Mohammad, a young entrepreneurial restaurant owner who recently opened a guesthouse, pointed out to me an area of choice farmland, smaller than a football field but near the center of town, that he estimated would currently sell for $24,000, an unimaginable sum to most of the town’s inhabitants. However, considering that Bodh Gaya was almost entirely feudal as recently as the 1970s, the improved conditions for many independent local business owners, even if they still pay rent, cannot be overlooked. Most of the temples in Bodh Gaya sponsor schools, making education possible for more of the town’s children than ever before. Many of the working poor of Bodh Gaya may be illiterate, but it’s safe to say that most of their children will not be.

Perhaps the most serious challenge facing both the local population and the pilgrims concerns the fate of a single square kilometer around the entrance to the Mahabodhi Temple. In 2002, the temple was declared a World Heritage Site by the grace of UNESCO. As a result of this potentially dubious honor, Bodh Gaya’s future seems to depend on neither the needs of the town, nor the desires of the pilgrims. Instead, in order to accommodate the increase in tourists, the national government is planning an overhaul of the town in the name of improved infrastructure. The Delhi-based federal Housing and Urban Development Corporation Organization has proposed a twenty-six-year strategy that would theoretically provide Bodh Gaya with more housing, drinking water, toilets, and greenery.

“Beautification means relocation,” says Bhikkhu Bodhipala, the Chief Priest of the Bodhgaya Temple Management Committee, which came into existence in 1949 and functions as a “catalyst” for funds and developments administered by the state government. This was the Chief Priest’s way of saying that if this master plan does actually come to pass, a one-kilometer radius surrounding the temple entrance will be demarcated as a “buffer zone,” in which no businesses will be allowed to operate. This would mean displacement at best—and closure at worst—for the vast majority of the shops in Bodh Gaya.

Under this plan, both Jamal’s shop and that of his son would be shut down and “relocated.” Bhikkhu Bodhipala reassured me that two proposed “market complexes” (which sound an awful lot like malls) on either side of town would not only house all the local businesses but also help to make the process of shopping “more systematic.” Jamal is understandably hopeful that this plan remains only a file on some Delhi bureaucrat’s desk. “The temple is nice,” Jamal said, “but here people are also nice,” referring to the busy road his storefront faces. A few shops up from Jamal’s is a barber, and at any given time of day during the monlams, it’s common to see seven or eight young Tibetan monks squeezed inside, waiting to get their heads shaved. Meanwhile, the mattress makers are busy stuffing zafus, and inside the Kalyan Hotel—an old, pink restaurant across the street from Famous Tailors—sit Tibetan women in their striped aprons, Taiwanese and French lay practitioners with their backpacks, and groups of Indian families in town for an afternoon of sightseeing, all drinking chai. This is the “nice” Jamal is referring to, and I couldn’t agree more.

THIS YEAR’S KAGYÜ MONLAM was broadcast twenty-four hours a day on a pay-per-view religious channel in Taiwan. At the monlam I met a group of fourteen Mongolians fresh from their first videocast retreat in Bombay. And not only were there battery-operated candles at the stupa, but they were collected at the end of the night just as carefully as they had been handed out. Even though I knew the smoke had been harmful to the Bodhi tree, I resisted the plastic candles until I realized how much fun some of the younger monks were having, swaying them like lighters at the end of a Journey concert.

There’s a new train that runs direct daily from Delhi to Gaya called the Mahabodhi Express, and on New Year’s Day the Gaya Airport, only a few years old, boasted four outgoing international flights. The dharma is clearly continuing to flourish where it first arose, even as the means of its manifestation may challenge our notions of how things are “supposed” to be.

While it would be wrong to say that Bodh Gaya does not struggle, it would be just as wrong to imply that this would somehow not be the case if it weren’t for progress. The Karmapa also reminded us, as we sat and shivered in the magnificent shrine room of the brand-new Tergar Monastery, that “we are all here to know one another more.” When everything is crowded, noisy, and televised, this isn’t always easy to remember. When we’re hurrying through dinner to race back to the temple or haggling over the price of a new zafu or trying to cross the street to Famous Tailors without getting hit by a rickshaw, it can be easy to forget the real reason we came.