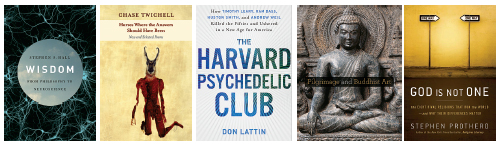

In God Is Not One: The Eight Rival Religions That Run the World—and Why Their Differences Matter(HarperOne, 2010, $26.99 hardcover, 400 pp.), Stephen Prothero argues against the assertion that all religions are simply paths to the same God. The book systematically breaks down eight religions—Islam, Christianity, Confucianism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Yoruba religion, Judaism, and Taoism—to show that at their core, each includes a four-part approach to the human condition: a problem, a solution to this problem, a technique for moving toward the solution, and finally an exemplar who charts the path from the problem to the solution. When religions are deconstructed in this way, Prothero argues, the differences between them are undeniable—Buddhists are not seeking salvation any more than Christians hope to achieve nirvana. Underlying the sometimes dry and academic tone of the book is a deep sense of urgency: Prothero cautions that it is not only naive to suggest that all religions are the same, it is dangerous. “To reckon with the world as it is,” writes Prothero, “we need religious literacy.” His book takes us one step further in that elusive pursuit.

In The Harvard Psychedelic Club (HarperOne, 2010, $24.99 hardcover, 272 pp.), Don Lattin takes us back to the early 1960s, when the paths of four men crossed and the psychedelic movement was born in the America. In their quest for spiritual enlightenment, Richard Albert (later to be known as Ram Dass,) and Timothy Leary founded the Harvard Psilocybin Project in the winter of 1960, a radical experiment with psychedelic drugs. Huston Smith joined from MIT, and Andrew Weil (a Harvard undergrad) propelled the experiment into the spotlight. As a contemporary who was there indulging in psychedelic experiments of his own, Lattin acts as a guide, weaving his way through the 60s and 70s to bring us icons of the era—John Lennon, Ken Kesey, Allen Ginsberg, and Joan Baez, to name a few—who float in and out of the story, lending their familiar images to the backdrop of the psychedelic era. Though Smith, Leary, Weil, and Alpert eventually went their separate ways, Lattin notes that together they set the stage for the mind, body, spirit movement of the next twenty years and forever changed the way Americans think about religion, medicine, mind, body, and spirit. Whether or not psychedelic history is your cup of tea, the book is definitely a trip to read.

It takes a gifted poet to turn an unpleasant scene at a movie theater into a poem. In Horses Where the Answers Should Have Been (Copper Canyon Press, 2010, $19.00 paper, 200 pp.), a compilation of her new and selected poetry, Chase Twichell explores moments of her life—moments of nature’s beauty, moments of death, moments in movie theaters. The collection of poems— spanning almost three decades—allows us to see Twichell’s evolution as a poet and as a person, as her poetry frequently explores concepts of self. From “Bad Movie, Bad Audience” (“The corpses of the future/drift across the galaxy with nothing/in their stiff, irradiated hands”) to “Solo” (“Nothing to watch but the snow,/the muted road slowly unbending”) to “Zen and Opium” (“a pure Zen Yankee candle, my flame a vow/to save all sentient beings, beginning with myself”), Twichell’s poetry is diverse, sometimes vibrant and quick, sometimes stark and cold, at other times quiet and contemplative. At its core, Horses Where the Answers Should Have Been is a collection of sacred moments, moments in which Twichell deftly turns the mundane into poetry.

“Wisdom,” the Buddha said, according to the Sutra of the Four Noble Truths, “lies in stilling all desire.” But what is wisdom, and how does one become wise? In Wisdom: From Philosophy to Neuroscience (Knopf, 2010, $27.95 hardcover, 352 pp.), Stephen S. Hall explores that ancient and mysterious virtue. The narrative takes the reader on a historical journey—traveling from China, India, Greece, and the Middle East in the fifth century BCE all the way to the present day, where the search for the source of wisdom has shifted its focus to the human brain. Hall’s work is rooted in both biology and history. After exploring the historical elements of wisdom, he turns his investigation to neurological research, probing the brain in an attempt to find the source of wisdom. But though Hall bravely attempts to put his finger on what wisdom is, it is clear by the end that the true source of wisdom remains elusive. And why do we hunger for something so indefinable? Hall argues that what drives us in our quest for wisdom is knowledge of our own mortality. “The path of the well-lived, virtuous life,” Hall writes, “has meaning precisely because that path arrives, for every living soul, by whatever circuitous route, at exactly the same destination.”

In the Mahaparinibbana Sutra, Ananda asks the Buddha how he can be venerated after his death. The Buddha replies that his followers should seek him in the places that he visited during his lifetime—the sites of his birth, his enlightenment, his first teaching, and his death. (Yale University Press, 2010, $65.00 hardcover, 224 pp.) explores the artwork that has arisen out of the tradition of Buddhist pilgrimage over the course of more than two thousand years. The book accompanies an exhibition of the same title at the Asia Society in New York through June 20, 2010, where curator Adrian Prosner brings together art from South Asian, Himalayan, Southeast Asian, and East Asian cultures to create a stunning and diverse set of images. The book features over ninety paintings, sculptures, textiles, and manuscripts held sacred in Buddhism. Complementing the imagery, scholarly essays explore the tradition of pilgrimage—the motivation, preparation, and journey—and the ways in which pilgrimage has influenced Buddhist art.

—Rachel Hiles