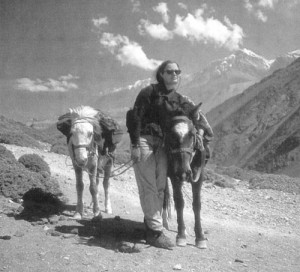

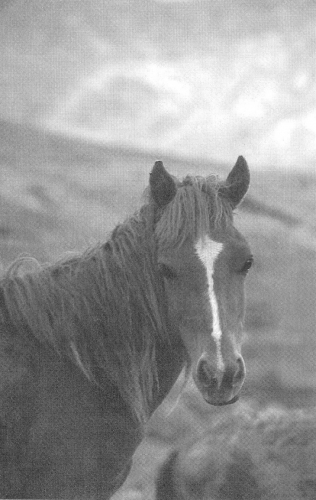

Midsummer in Mustang is bright days and early starts. We’d been riding since dawn. Too many stops for tea the day before had slowed us, yet we needed to reach Jomosom from Lo Monthang in two days and intended to move quickly south. Chandra’s rhakpa, a charcoal-colored mare, was pregnant. She had been trying to keep up all day. Though well-fed and muscle-toned, she struggled up the morning’s passes and was panting by noon, sweat trickling between her ears. The mare was about a quarter of the way through her gestation period, according to Gyatso. A local doctor (amji), he has treated many a horse and was attuned to signs of this new life, half formed, shifting inside her.

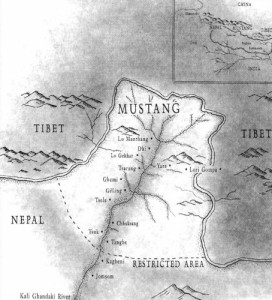

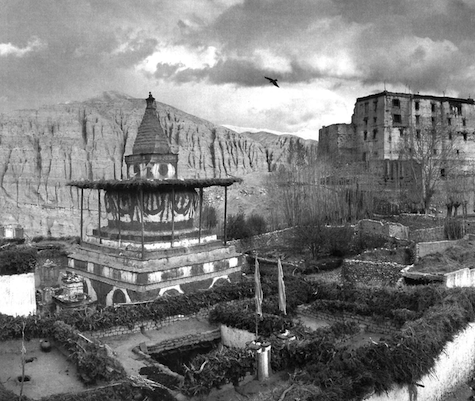

The kingdom of Mustang, Nepal—or “Lo” as Mustang is called in Tibetan—is high-altitude steppe and desert, a geography akin to the Tibetan plains to the north. Though closed to foreigners until 1992, Lo has been a trade route and pilgrimage site for centuries. The present king of Lo is twenty-fifth in a lineage of monarchs dating to the fourteenth century. Like people across the Tibetan plateau, Loba (“people from Lo”) rely on trade, agriculture, and animal husbandry to survive. As in other enclaves of Tibetan civilization, the horse in Mustang is at once an indispensable means of transportation, a symbol of wealth, and a religious icon. This region’s rugged terrain, its expanses of wasted, sandy plains, and Lo’s comparatively meager fodder supplies demand that riding horses—more delicate and expensive than yak, sheep, goat, even other porter horses—be guarded against as much hardship as is possible in this difficult landscape.

Chandra rode quietly and tried not to push his horse. The king of Mustang’s personal secretary for twenty-one years, Chandra is savvy, diplomatic, and looks clean even in dust storms. He realized that the developing foal, if born healthy and trained well, would fetch at least 50,000 rupees ($800) at the local market; a miscarriage, however, would only harm his mare. The day had begun to wane and Jomsom was still several hours’ ride downriver, but Chandra wouldn’t let us hurry. Instead, he let loose the reins, lowered his head, and dozed, lulled to sleep by the easy rhythm of his mare’s walk.

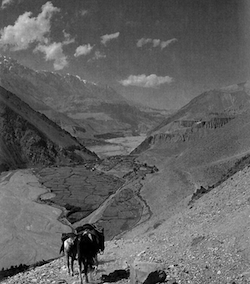

We dismounted and began the rapid descent to Tsele. Chandra’s mare lumbered with the added weight of the life inside her. She shied away from a piece of rock that broke off from the cliff and came tumbling down. The mare was alert and protective, guarding the vessel of her body as she stepped gingerly through this dangerous corridor of falling scree and dust the color of turmeric.

“See the way the baby flips in its mother’s stomach while she drinks? Maybe the foal is a lake horse,” Gyatso pondered as the mare drank. Tibetan legends speak of horses fathered by stallion deities who live at the center of lakes, emerging only to mate with mares grazing near the shore. Developing foals fathered by such stallions are said to “swim” inside their mother’s wombs. Mares birthed from such unions are thought to travel with exceptional strength and ease, as if moving through water. Colts, however, don’t like to approach water for fear of being paralyzed by their father’s reflection, of not knowing to which world they belong. Lake horse or not, I hoped the unborn foal would survive Mustang’s bleak winter and imagined it grown—as tenacious and fluid as the current that carried us home.

We would not reach Jomsom until dusk, and already my back was bent in pain. I had taken a bad fall off Gyatso’s new horse, freshly imported from Tibet, a few days before. My body still ached from simple movements. The crick in my back, stiff in the morning, had me moving with the lethargy of a bowlegged cowboy. In the evening, I had to rest one hand on my hip as the other hand separated saddle blankets, pulled off bridles, and doled out the evening’s grain. As I worked, I couldn’t help thinking of that dro-mar of Gyatso’s, the red-tinged “blue” horse that had thrown me. Everyone had warned me not to ride it: the father of the house in which I live in Monthang; the old men who sit spinning wool, prayers, and gossip at the gates of this city; even the king of Mustang.

“Horses from the chang tang [Tibet’s northern plains] are dangerous,” The king mumbled late one afternoon. “Let Pema Ngotug ride the horse first, then you can ride.” Pema Ngotug, all muscle and grit until he smiles, is one of the king’s closest attendants. The musket he carries whenever the palace entourage departs makes Pema the king’s bodyguard. Pema has been doctoring, trading, and breaking Mustang’s horses for years. His body bears the scars of countless mounted misadventures: the ridge of his nose, at least thrice broken; fingers that form a contorted, yet solid fist; feet that rest more naturally in stirrups than on the ground.

But Pema Ngotug had gone to the village of Drakmar to monitor the cutting of the king’s fields and the horse was there, saddled and looking docile. I decided to try. It wasn’t the first time I had broken a horse, nor would it be the first time I took a bad fall, I reasoned, even though I knew many people would be worried if I did.

There is a saying in Tibetan that likens the Buddhist concept of “mind” to a horse: a powerful tool rendered useless without training and discipline. Likewise, lung-ta, often translated as “wind horse,” is not only the name given to the prayer flags embossed with the image of a horse delicately balancing the jewels of Buddha’s teachings, Lung-ta is also a Tibetan Buddhist practice, a series of initiations and teachings that is both the “universal foundation” (klung) implied by vast space and the “excellent horse” (rta mchog), a symbol of traveling with wisdom, transmuting obstacles, illusion, and misfortune with the greatest speed..

Yet, the sort of insight buried within the Lung-ta teachings never comes instantly. Much plodding is required before one can ride on the wind. I found out later that Gyatso’s dro-mar spent the week after he threw me threshing sweet peas—a deliberate lesson in humility that left him quiet and rideable, but still green. I, too, had much to learn. This movement of horse and rider towards each other is nothing if not an act of discipline and subtlety, of skillful means and trust.

I had been in Mustang for six months now. Dips and peaks along the trail and the distances between villages were no longer a surprise. I felt confident traveling on my own. It was time for me to leave Lo for a quick trip to Kathmandu. Raju, the king’s nephew, gave me for the ride south a crow-colored gelding that had once belonged to a Tibetan nomad. Judging from the marks on the horse’s teeth, the animal was nearly eleven—well beyond middle age for most of Mustang’s horses. The tips of his ears had been split soon after birth, earning him the nickname na shi, or “four ears.” Raju explained that the ears of horses born to mares that have lost previous foals, or foals born sick, are split. This maiming is thought to ground a sentient being in its body. Once scarred, the horse is “imperfect” enough to remain in this world. Now grown, this gelding was one of Raju’s strongest. We left Monthang early, alone.

The stretch of trail after Samar invited speed. If the horse had been young, or if I had been less familiar with the trail, I might have been anxious. As it was, however, any sense of nervousness was dispelled by a joyful harmony of eyes and arms and solid seat, hooves and mane and half-pinned ears. Left hand raised and gripping reins, feet clicking forward at the girth, right hand flicking whip at my mount’s right eye, but never touching horseflesh. A vehicle in the true sense of the word, this seasoned horse was teaching patience, lending speed to the grace of this rugged landscape. I could feel the gelding’s power well up from behind. The strain of muscles, his and mine, became as seemingly effortless as exertion can be. A moment of balance found: lost, found again.

Mustang is in the rain shadow of the Himalaya, but is not entierly immune to monsoon. Clouds had been gathering all day. The sky darkened behind me, turning indigo over Lo and the Tibetan plains to the north. Lightning split the sky. Then it cracked: thunder, “sound of the dragon” in Tibetan, shook the earth. Raju’s horse had been undaunted by steep hills, high waters, porters carrying boxes and planks along the trail; but now, as the storm broke, he stopped short and whinnied at the northern sky and pawed the ground, answering the thunder.

A Tibetan refugee once told me, “Whenever a horse hears thunder, it will remember its birthplace. Some horses try to run back. Thunder is like the heartbeat of Tibet.” The northern plains on which this horse had been born were enveloped in storm.

We arrived in Jomsom drenched. Small rivers ran between houses, over slate cobblestones, down to the swollen Kali Gandaki. Willow trees kneeled under the force of the downpour. When we pulled into Chandra’s house, both the horse and I were shaking, steam rising from our bodies like smoke from the kitchen fire. I unsaddled and stabled the black gelding, Chandra’s wife prepared tea, Chandra fetched the horse some grain, and we began to dry off.

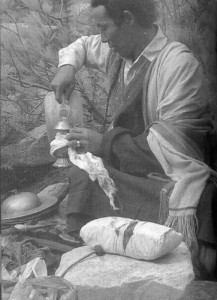

My mount was feverish by next morning. His nose ran and his eyes were dull. My hosts had gone out, and the horse needed immediate care. I decided to call on Mayala, one of Mustang’s renowned local veterinarians. This old man had spent nearly ten years with Tibetan nomads, trading horses and yak, sheep and salt, learning how to care for animals. Although the corpus of Tibetan medical texts includes veterinary volumes—horse texts, in particular—and though these books exist throughout Mustang, Mayala’s expertise lived in his skilled hands, not among the pages of such books. He was in constant demand. Even the king, an excellent veterinarian in his own right, called upon him to let blood, prepare herbal remedies, cauterize wounds.

“Mayala is difficult. If I had asked him, he couldn’t have refused. But you’re just an outsider to him,” said Chandra, embarrassed. He has seen enough foreigners—tourists and researchers alike—pour in and out of Mustang. Our friendship aside, this was to be a teaching, if not an initiation.

“Mayala has taken care of horses for nearly forty years,” continued Chandra, shedding his smile. “All that work with blood and fire, iron and disease, sometimes death has exposed him to much pollution [grib].” I imagined this terse and rugged bodhisattva, his acts of compassion, if not inverted, rendered impure by the elements from which they sprung.

“Mayala is old and superstitious. He wants to retire, but villagers still come to him and he must help them.” Chandra sighed. “Don’t worry. I’m sure the horse will be fine.”

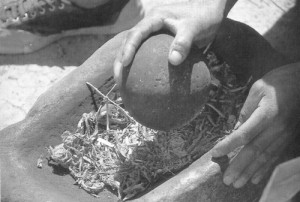

By the time I returned to Chandra’s to check on the horse that evening, Mayala had visited and prescribed twelve black hay beetles, ground live and mixed with grain to quell the fever; juniper incense; and a protection ritual (Rta-srung) performed by a village lama to reach the horse’s mind, the root of its disease.

If it hadn’t been for the vultures, perhaps Gyatso and I wouldn’t have noticed the corpse and instead ridden on toward Lo. But Gyatso spotted the body and we rode up to investigate. The horse’s frame lay unmoved. A lump on the horizon, this dead horse did not draw attention to itself, but instead receded into the Mustang landscape: ruins, desert wildflowers, and suede-colored hills. The animal must have died no more than forty-eight hours before. Although only tufts of dried grass remained where there had once been tongue and nostrils and tail flesh, the horse’s skeleton was mostly intact. Yet the skull, once a web of delicate lines, had been smashed as an invitation to vultures to feast on the body. Such sky burials in Tibetan are known as “giving to the birds.” Since vultures do not kill their prey, their presence at the sight of a death is considered cleansing, both physically and karmically.

Gyatso guessed the horse was about thirteen. Its teeth hinted at scars—from a bit—and, therefore, mounted training. Its hooves bore no shoeing marks. This horse, like countless others of its kind, had spent its life walking through this river valley, carrying loads. A sunken rib cage suggested a death brought on by slow starvation, internal parasites, and perhaps the dreaded “hot” disease that Lobas attribute to winter migration south—a shift in transhumance patterns necessitated by the closing of the Nepal-Tibet border.

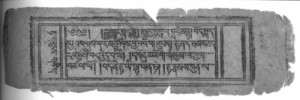

bum chung as this horse was laid to rest. Literally “concise vessel,” the bum chung text is a short summary of the Prajnaparamita(“Perfection of Wisdom”) scriptures. This text helps guide the dead towards auspicious gateways of rebirth, and can be read for the benefit of humans and animals alike.

“If the bum chung is not read, beings dead to this world can wander toward realms of hell and hungry ghosts,” explained Gyatso. Sometimes a Loba will even place his dead horse’s head on the roof of his house to ensure that his wealth and property, embodied by horses, do not “die” with the animal. If the dead horse had been a prized mount, the exposed burial ground might have been scattered with remnants of a ritual: charred incense, grains, dabs of butter, the smell of spilled chang(barley beer). As it was, there was only heat and dust, wind, thin mountain air, and a trail littered with hoofprints leading north.

By late July, Lo Monthang’s fields blazed with cadmium mustard flowers and pale pink buckwheat when Gyatso and I arrived. The Loba were busy directing irrigation canals, passages without which their villages—oases of cultivation—could not exist. Water ran clear these days, pure as medicine. Each year at this same time in late July, Mustang’s horses are bled from their noses and bathed in streams running high with new glacial melt. This shedding of “old” blood is a ritual of renewal that prepares horses to move to high summer grasslands. Spilled blood is mixed with grains and fed back to the horses. Life force reborn as sustenance.

I left Monthang at daybreak and headed for the king’s yak pastures. All thirty of his horses had been brought there the day before, as the bloodletting and baths would begin at first light. The king, Pema Ngotug, and a handful of helpers were soaked, their pants stained by grass and blood by the time I arrived. All but the king’s favorite horses had been bathed, bled, and let out to pasture. I sat watching as one musclebound beauty followed another into the water, through this ritual. It was, no doubt, the finest showing of horses I had seen in Mustang.

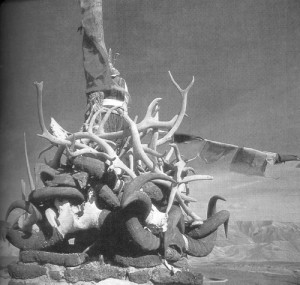

Until the final horse. It seemed a bit unusual that the king would save a dingy-looking two-year-old for last; but it didn’t take long for me to realize that this animal was more than just a horse. For months now I had been hearing about a god-horse (lha-rta) said to be one emanation of Dung Mar, the king’s protector deity. Considered Dung Mar’s mount, this horse is never ridden, but instead roams free. After the horse dies, a new incarnation must be quickly named by the king. Any gap in the Dung Mar lineage could disrupt the balance of this living landscape.

Such god-horses surface as protector deities and village guardians throughout the Tibetan-speaking world. Perhaps the most famous of such god-horses is Kyang Go Karkar, the mount of Gesar of Ling, Tibet’s famous warrior-king, whose life is recounted in epic song across central Asia. As the story goes, a tulku (reincarnate lama) was sent from the realm of the gods to become Gesar’s mount. Endowed with the wisdom and compassion required of dharma warriors, this pair fought many battles against evil, illusion, and ignorance, emerging victorious in what must be seen as a brilliant expression of both Tibetan Buddhist precepts and the banditry and fierce, mounted combat that is as much a part of Tibetan history and culture as butter tea. After all, four centuries before the great Mongol hordes swept central Asia, Tibetans on horseback had established a vast empire across much of the same territory.

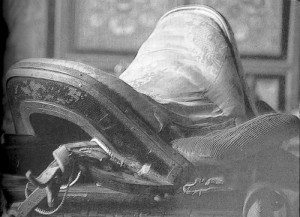

I stared down at the valley below—a place of cavernous rock, caves, and the ruins of fortresses—thinking of Gesar, seated beside a benevolent king from a different age. The king of Lo glanced toward where the young Dung Mar was grazing. Though this half-grown stud bore the markings and color demanded of these horses—red body with white socks and blaze—he seemed no match for his previous incarnation. Most Loba recall the last Dung Mar as a fearless beast, deep chestnut in color, who led the procession at a yearly harvest festival saddled in gilded silver and turquoise, coral and gold. Though riderless, the horse would prance and sweat, moving with the conviction and grace of a god.

The young Dung Mar leapt across marshy tundra and refused to be caught that summer morning. The king, not one for sloshing through bogs, handed Pema Ngotug a rope and sent him off to fetch the colt.

“The last one,” said the king, gesturing toward the young horse, “was surely Dung Mar. This one, well . . .” He paused. “I’m actually still looking for the next real Dung Mar, but this horse will do for now. He has to.” The king looked east. I followed his gaze toward Samzong, a village at the outer reaches of his kingdom.

“Samzong used to be the richest village in Lo” the king mused. “People there had water, fields, plenty of pastures. Dung Mar horses were born there for at least five generations. The horse that died two years ago was the last to come from Samzong. Now those pastures have turned to desert, the river is drying up, Samzong is the poorest village in Lo, and this two-year-old is nothing compared to his forefathers.”

Pema Ngotug returned with the special colt in tow, coaxed the animal into the river, and bathed him. The animal—faith manifest in horseflesh—was not enough of this world, however, to be bled. Half wild, Dung Mar leapt out of the river and galloped off, pausing only to shake water from his mane and nicker at the king. Here was the pulse of Mustang’s landscape: a world skittish and strong as this young colt, but haunted by the ghosts of greatness.