In the summer of 1958, Michael Dillon stumbled up a mountain path in Kalimpong, India, gasping in the thin air. He was a British gentleman gone to seed, with an unkempt beard and a pipe stuffed into one pocket of his rumpled suit. He often glanced over his shoulder, as if someone might be chasing him.

Dillon was on his way to a monastery run by an Englishman. He guessed it would be the kind of place where you could become invisible. Hidden on a mountaintop in the Himalayan foothills, you could lose your identity and start a new life.

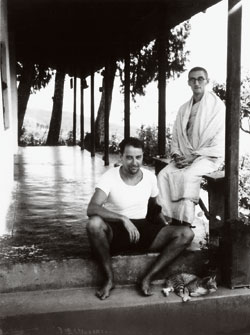

Finally Dillon came around a turn and spotted a dormitory perched on the side of a cliff. A white man in a yellow robe stood on the building’s porch; short, with a shaved head and huge horn-rimmed glasses, he resembled a stern owl. The man waved and welcomed Dillon to come in. Speaking with the accent of a working-class Londoner, he introduced himself as Sangharakshita. Born Dennis Lingwood, he dropped that name when he was ordained as a Theravada monk. (Sangharakshita went on to found a British community called Friends of the Western Buddhist Order, which now has centers in over a dozen countries worldwide.)

By way of explaining his own situation, Dillon reached into a pocket, fished out a newspaper clipping, and handed it to the strange little yellow-robed man. The monk peered through his thick glasses and read the clipping. It was a gossip column concerning a British woman, Laura Dillon, who had changed her sex. She had transformed herself—legally and medically—into a man, and was now living as a doctor named Michael Dillon. As a male, Dillon stood to inherit an estate and a title: someday, he would become the ninth baronet of Lismullen.

Sangharakshita handed the newsprint back, and the two of them exchanged a long, significant look. This was a bombshell. Five years before, Christine Jorgensen’s sex change had become the number one news story in America; when Jorgensen appeared on TV bedecked in blonde curls and designer gowns, the public understood that it was possible to metamorphose from man to woman. But few people—even top doctors—knew that the human body could go the other way, too. Dillon had been the first person ever to undergo a medical transformation from female to male. He was a worldwide tabloid story waiting to happen—if the journalists ever managed to find him. A few weeks earlier, they had located Dillon in Baltimore, where he was working as a ship’s doctor. A gaggle of newshounds had descended upon him with their notepads and flashbulbs, lobbing questions, threatening to tear off his clothes in order to see the evidence of his sex change. And so Dillon had fled to India, to the most out-of-the-way spot he could find.

Within the next few days at the monastery, Dillon revealed far more to the monk, spilling some of his most closely held secrets. Dillon confided that he had “an artificial penis, constructed out of skin taken from different parts of his body,” according to a recent email from Sangharakshita, now in his eighties. “He was very proud of this organ, and offered to show it to me, but I declined the offer. . . . He also told me that he was taking hormone tablets to promote the growth of facial hair and to suppress menstruation.”

In his own writings from the 1950s and 1960s, Dillon claims that Sangharakshita promised never to repeat such confidences to anyone. “I trusted him because he was both a fellow Englishman and a monk.”

Sangharakshita, for his part, insists that he never made any such promise. After all, he was not a Catholic priest, obliged to hear confessions under a seal of secrecy; he had no professional obligation to protect Dillon. Right from the beginning, the two men misunderstood each other completely.

On his first night at the monastery, Dillon pulled out his pipe and stood on the veranda. Instead of lighting up, he hurled it out into the darkness, where it tumbled into the abyss of the valley. In the following days, he would hurl his name away, too—the “Michael” that he’d picked for himself and the “Dillon” that had linked him to generations of ancestors. He asked Sangharakshita to rename him, not so much for spiritual reasons as practical ones. He needed to lose his English identity. So Dillon became “Jivaka,” a name inspired by the doctor who had tended the Buddha.

Related: A Big Gay History of Same-sex Marriage in the Sangha

Weeks or months later, to complete his disappearing act, Dillon shaved his beard. He removed every last piece of evidence that would mark him as that “sex change” in the newspaper clipping. In the process, he stripped away all the props that he’d adopted years before to help establish his male identity: the pipe, the facial hair, the Michael. Jivaka would be another sort of person entirely. Dillon was a man in exile, desperate to find someone or something to build his new life around. For now, he only had Sangharakshita, who included him in morning rituals, showed him how to meditate, and assigned him chores.

Sangharakshita happened to be writing a book just then, a memoir that explained how he’d started as a poor boy in London and ended up running a monastery in India. Dillon became his secretary. Even though he’d earned degrees in theology and medicine from Oxford and Trinity, respectively, Dillon performed this menial work without complaint. He was eager to please his new teacher and began referring to Sangharakshita as his guru.

During those long, slow afternoons at Kalimpong, while slavishly typing drafts for the monk, Dillon got an idea: he decided to write his own autobiography. In his own manuscript, he struggled to make sense of all that had happened to him, pouring out the very secrets that he’d come to India in order to protect. Day after day, the pile of delicate onionskin pages grew taller; inside those pages, Dillon was able to reinvent and reimagine the life he’d just escaped; he lavished special attention on his description of his childhood as an aristocratic girl in a seaside town.

When Dillon stepped away from the desk, he remained a child of sorts. Sangharakshita expected him to obey orders, eat whatever he was served, and sleep where he was given a bedroll. Soon the two men had forged an intimate and strange relationship. Dillon began to call his guru “Daddy,” an endearment that Sangharakshita apparently tolerated. “I did not really like [it], especially as he was ten years older than me,” Sangharakshita remembers.

After a few months, Sangharakshita announced that he would spend the winter traveling around India. While he was gone, Dillon would stay with a group of Therevada monks at the Maha Bodhi Society guesthouse in Sarnath, more than three hundred miles west on the Gangetic plains.

In Sarnath, the site of the Buddha’s first sermon, Dillon blossomed. He devoured books on Buddhism and wrote articles for small journals under the name Jivaka. Buddhism meant more to him now than just a hiding place: it had become a refuge from his mental pain. Above all, after spending most of his adult life friendless, fleeing from place to place, he dreamed of belonging to a community of Buddhist monks. That winter, according to his unpublished autobiography, he took vows as a novice in the Theravada tradition.

When spring came, Dillon returned to Kalimpong to resume his life as Sangharakshita’s protégé. He had been looking forward to settling into his old room at the monastery, particularly now that he wore the robe of a novice. If he hewed to his vows for a year or so, he might be allowed to take the higher ordination and become a full-fledged monk. He expected Sangharakshita would recognize him as someone who could one day become an equal.

The guru did not. As Sangharakshita saw it, Dillon was a woman and therefore completely unfit to take vows in the male community. To this day, Sangharakshita believes that a sex change does nothing to alter an individual’s identity. “Jivaka was not able to beget a child [as a man],” he asserted in an email. “To my mind it is this factor that determines the gender to which one belongs.”

Dillon, for his part, felt so ill-used by his guru that after a few months he decided to leave the monastery and seek his fortunes elsewhere. And so in the fall of 1959, he packed up his few belongings and returned to the hostel in Sarnath, to study and meditate—and to contemplate how he might still bend the rules and become a monk. He’d discovered a law in the Vinaya, the Buddhist monastic code, that alarmed him: anyone who belonged to the “third sex” could not be ordained. It wasn’t clear to Dillon what the twenty-five-hundred-year-old Vinaya originally meant by the term “third sex,” but he was pretty sure it applied to him. Eventually, he worked up his nerve and approached Theravada leaders in Sarnath, confessing his secret. The leaders conferred and gave him an answer: Dillon could remain a novice but could not become a full-fledged monk. He was devastated. For the rest of his life, he would denounce the Theravada tradition as rigid and hierarchical.

The year before, when he fled from the tabloid press, Dillon had chosen India as his hideout partly because he had hoped to meet Tibetan refugees there. Like so many other Englishmen of his time, he’d read accounts of flying lamas who practiced mind control, who had their “third eyes” opened by hot pokers. By now, of course, Dillon realized those stories were more myth than reality; still, he remained in awe of Tibetan Buddhists. When the Theravada monks rejected him, he decided to find out whether the Tibetans might be kinder toward transsexuals.

That year, 1959, Tibet was on everyone’s mind. China had invaded the country and installed its own government. Many of Tibet’s most talented teachers, who were now in danger of being jailed or killed, trekked over the Himalayas and scattered across India. In Sarnath, Dillon lived surrounded by Tibetan refugees. It was the Gelugpas, or monks of the “yellow hat” sect, who most struck a chord with him. They had been Tibet’s philosophers and bookworms, and now they had flooded into town to eke out an existence, arriving dizzy with grief and hunger. He guessed they would be sympathetic to him, for he was as much an exile as they were. Through a translator, Dillon asked Denma Locho Rinpoche—an eminent Tibetan monk—about his “third sex” dilemma. As he had hoped, the rinpoche agreed to ordain him, and they set a date for the ceremony. To make sure everything was properly arranged, Dillon wrote a letter to Sangharakshita, asking him to come to Sarnath to act as an English-to-Hindi translator and to preside at the ceremony. Somehow, in the months since he’d left Kalimpong, Dillon had managed to convince himself that Sangharakshita—his “Daddy”—would be proud of him.

The reply was hardly what Dillon had expected. Sangharakshita fired back a letter, in triplicate, to the rinpoche and other leaders in Sarnath. The letter revealed Jivaka’s Western name and spilled details of the sex-change operation. According to Dillon, it also included many false accusations. Sangharakshita still believes today, however, that he had no choice but to write the letter. Dillon intended to break monastic law, and Sangharakshita refused to be a party to that.

One Saturday morning, the rinpoche handed Dillon the letter and explained through a translator that the ordination was off because he was reluctant to offend Sangharakshita. Dillon’s hopes were again shattered. But all was not lost. Dillon had been lucky to strike up a friendship with the well-known German professor Herbert V. Guenther, then in residence at nearby Sanskrit University in Varanasi and an expert in Tibetan traditions. On a sweltering day in November 1959, Dillon arrived at Guenther’s office for lunch. That afternoon, the professor spun a tale about a fabled monastery called Rizong. It was in Ladakh, a small Himalayan kingdom on the Tibetan border. High up in the mountains, in an area that was nearly impossible to reach, the monks of Rizong practiced Tibetan Buddhism in its purest form, adhering rigidly to rules set down centuries before. Guenther had never been to this monastery; at that time, it would have seemed an impossible destination. India, on the brink of war with China, controlled Ladakh and kept the borders tightly sealed from all suspicious foreigners. Certainly, a rogue Englishman with a secret past would never be able to get into Ladakh. Rather, Guenther offered up Rizong as a fable, a vision of monastic Buddhism taken to its furthest extreme. Dillon accepted the story in that spirit—Rizong, like Tibet itself, seemed as much an idea as it was an actual place.

Still, he persisted in trying to find someone who would ordain him, some way to belong to a Tibetan community. A few months later, Dillon managed to wrangle a meeting with Kushok Bakula, a prince in the royal family of Ladakh. Dillon poured out his woes to the prince and asked how a “third sex” man might become a monk. As Dillon later reported in his autobiography, Kushok Bakula “gave me a look of compassion which I will never forget.”

The prince assured Dillon that he could one day be ordained. But until the controversy blew over, Dillon would only be allowed to take vows as a novice in the Tibetan tradition. (While there was a ban against monks who belonged to the “third sex,” no such ban existed for novices.) Dillon would be able to enter a monastery in Ladakh, but only if he would inhabit the lowest rank, on par with the ten-year-old boys. Kushok Bakula had picked out the monastery where Dillon would be sent: by chance, it happened to be Rizong. In the spring of 1960, Dillon arrived at the monastery without any money, not even a decent pair of shoes. He would stay for three months in its tumbledown buildings, set against the lunar landscape of a Himalayan mountaintop, until his travel permit ran out. Dillon insisted that he should be treated like any other novice who came to the monastery, with no concessions for his white skin or advanced age. He would take on exactly the same duties that the boys did, which turned out to be round-the-clock cooking and cleaning in Rizong’s filthy kitchen. The staff woke before dawn and worked until nightfall, but their day was punctuated with pranks, good-humored teasing, and laughter. They horsed around, dumping each other in the firewood box. “No one minded; no one’s dignity was hurt,” Dillon later wrote of his experiences at Rizong.

Related: Working Through the Strong Emotions of Sexual Identity

One time, he put his hand out to balance himself on what he thought was a wall: it turned out to be a loose piece of wood paneling. In a Charlie Chaplin-like pratfall, he leaned vertiginously, the wall leaning with him. For a moment the busy kitchen turned into a screwball comedy, and then Dillon and the wall crashed to the floor. There was “great merriment at my expense. But the laughter was so spontaneous and good-natured that I felt no embarrassment and joined in it. In those early days I was always doing something that amused my companions.” For the first time in his life, he could laugh at himself. Something had loosened inside him, some channel to joy had opened up. The old Michael Dillon had melted away, and a new man, the English novice—white skin gone gray with soot—had taken his place. The greatest surprise of all was this: starved, overworked, and filthy, Dillon had finally stumbled across a fragile kind of happiness.

The three months flew by. Dillon decided Rizong was his true home, and wanted nothing more than to stay. But when his permit ran out, he had to leave or face prison. If the ceasefire between India and China continued through the spring, Dillon hoped to return to Ladakh then. He imagined a future in which he could belong to this warren of tiny doorways and halls, with its chink-hole windows that winked with views of blue mountains, and to these men and boys he’d come to love. And he was thrilled with a promise that the abbot of Rizong, Kyabje Rizong Rinpoche, made to him: When Dillon returned, he would take vows as a monk and become a ranking member of the community.

For now, though, all he could do was wait in Sarnath. There he resumed his old life: he slept at a guesthouse, meditated in the mornings, and spent the rest of the day working on a typewriter borrowed from a friend. Dillon depended on the meager income from his writing to survive. Soon he would make his literary debut in England under the name Lobzang Jivaka, publishing a condensed and adapted version of the W. Y. Evans-Wentz translation of The Life of Milarepa, the story of Tibet’s famous saint. He was of two minds about his upcoming book: he badly needed the money, but feared that someone in England might connect him with the recently vanished Michael Dillon. “I do not wish my Western name known. I am heir to a title and have no desire for publicity. Only six people know where I am or what I am doing,” he wrote to Simon Young, his editor at John Murray Publishers, to whom he also refused to reveal his legal name. With his book finished, he poured out the first few chapters of another book in a mere matter of weeks. This one told his adventures in Rizong. Titled Imji Getsul (English Novice), the book is more a love story than anything, a paean to the home he’d found and then lost. He sent three chapters to his agent in London, and Routledge snapped up the tale written by the mysterious Lobzang Jivaka.

Dillon banged out the rest of Imji Getsul in the last weeks of 1960, while he lived in Sarnath; in order to conceal his identity, he had to pepper it with fabrications when he described his “boyhood” and his experiences as an “Oxford man.” It pained Dillon terribly to tell such lies, but he felt he had no other choice. That spring, he mounted a trip to Kashmir to visit Kushok Bakula, the prince who had helped him earlier. Dillon hoped to obtain a travel permit to return to Rizong, but the Indian officials turned down Dillon’s application. War was brewing in Ladakh, and Western travelers were not welcome.

The next spring, both The Life of Milarepa and Imji Getsul appeared in British bookstores, and Dillon braced himself for trouble. Surely, some reader would wonder about the secret identity of Lobzang Jivaka and make inquiries. He decided he could no longer bear to sit around waiting for the press to expose him, to lie about his past, and scuttle around with secrets. He would come clean, no matter what the cost.

On May 1, 1962—his forty-seventh birthday—Dillon pecked away on a typewriter in Sarnath. He had decided to finish the autobiographical manuscript that he had started years before. The manuscript told the story of Laura Dillon and her disgust with dresses, her grinding desire to be male, the testosterone that morphed her body, and the endless surgeries to get a penis.

He typed “by Michael Dillon” on the cover sheet and then hit the carriage return and added “Lobzang Jivaka” underneath. He would write under both his names. No one could threaten him now. No tabloid could get the scoop. He had lifted the mask himself. When the book came out, he would belong to a despised minority. But he would also live more authentically, more freely, than he’d ever dared to before. He packaged up the pages in an envelope and sent it to his London agent.

Days later, Dillon headed to Kashmir to renew his efforts to enter Ladakh, but he never made it there: during a stopover at a hostel, he succumbed to illness. No one seemed able to say what type of sickness had caused his death. According to Sangharakshita, a rumor circulated that Dillon had been poisoned, but there is no proof of that. The details of his death remain an open question.

Dillon’s body was cremated and the ashes scattered in the Himalayas. His autobiography nearly burned up, too: after he died, his brother demanded possession of the manuscript, which he planned to toss in the fireplace. However, Dillon’s literary agent fended off the lawyers and held on to the manuscript. To this day, it remains in storage in the agent’s warehouse. So Michael Dillon never did get his chance to reveal himself—except, of course, in those translucent pages pocked with words written on a borrowed typewriter.

♦

Editor’s Note: Michael Dillon/Lobzang Jivaka’s autobiography was published posthumously in 2017 as Out of the Ordinary: A Life of Gender and Spiritual Transitions.