The other day I was forced by a journalist to try to formulate my views on the main requirements of somebody who wishes to contribute to the development of peace and reason. I found no better formulation than this: “He must push his awareness to the utmost limit without losing his inner quiet, he must be able to see with the eyes of the others from within their personality without losing his own.”

Beyond obedience, its attention fixed

on the goal—freedom from fear.

Beyond fear—openness.

And beyond that—love.

—Dag Hammarskjöld

There is a question that many readers of Tricycle must feel. It is difficult to put into just the right words—words not dreamy or wistful, but a statement of factual need and realistic hope: In our troubled era, and no doubt the troubled century ahead, can there be an enlightened politics? The question needs at once to be embodied: Can there be enlightened politicians? What would such men and women be like? How would they conduct their outer and inner lives? What could be expected from them? Presumably they would not raise their voices, however eloquently, from protected places. Accepting the world on its own terms, they would wholeheartedly enter in. Through excellence the world has no difficulty recognizing, they would earn influential places from which they can be effective. And apart from those who are members of religious orders, it is likely they would choose to conceal their spiritual lives, although much of what they do and say—points of view advocated, decisions and processes for which they take responsibility— would be marked by something exceptional that would command respect in others. Their spiritual orientation would be known only to themselves and a few intimates: were it widely known, they would run the risk of dilution for themselves and mistrust from colleagues who naturally prefer a surface without mysteries. And if, in the end, they could not overcome the difficulties they had done their best to face and remedy, then they would leave a trace in words and acts for the next generation, some of whom would recognize that trace for what it is and begin again.

To whom can we look to model something of all this? We need to be intelligent in our use of models; each great man and woman to whose example we might turn was or is inimitable. They received a certain education in a certain culture, belonged or belong to one or another distinct spiritual tradition, have a certain heredity, language, and gift, and their political context was or is specific. The tragedy of models is that they are fundamentally inimitable. Yet there is so very much to learn from them. At best they make us turn, informed, toward ourselves and our era.

Dag Hammarskjöld has a place here; he is one of them. And in this year, the 51st anniversary of his death in an air crash in central Africa while on a peacemaking mission, can we join the United Nations and his native Sweden in summoning him to a new conversation? Hammarskjöld was the second secretary-general of the United Nations, serving from April 1953 to his death in September 1961. Born in 1905 to an aristocratic and hardworking family—his father was the Swedish prime minister during World War I and a lifelong advocate of international law—he was raised and educated in Uppsala and came early under the influence of remarkable Christians for whom religion was not just belief and a weekly chance to be among friends but a personal discipline and a call to action.

After studying literature, languages, and law at Uppsala University, he completed doctoral studies in economics in Stockholm and entered government service. He advanced quickly. When he was recruited to serve as secretary-general of the UN, he was a member of the Swedish cabinet, desolately wondering what might come next—perhaps nothing much. He came to the UN almost entirely unknown. He was not a world figure. Influential diplomats knew him and believed he would be a sound, apolitical administrator.

Hammarskjöld was much more than that. He actively thought about the UN in all of its dimensions, as if it were an object of contemplation that he could build in his mind and then build in the world. He shared his vision in a way that energized the organization and endowed it with new dignity. His political wisdom is evident throughout his public talks, press conferences, UN interventions, and private correspondence. The challenges he faced are part of our history: the seemingly endless Cold War of words and actions at the UN and worldwide; an opening to China long predating Richard Nixon’s; the first use of shuttle diplomacy, the Arab-Israeli conflict; the Suez Crisis of 1956-57; the creation of UN peacekeeping forces; regional difficulties of all kinds; the defense of his office against a wild attack by Khrushchev; and at the end, the Congo Crisis that led to his death, in which the UN under his guidance brought peacekeeping and administrative resources to Patrice Lumumba’s newly independent nation in an effort to rescue it from chaos and avert East-West interference.

With the publication after his death of his private journal, Markings, an unknown dimension of the man became apparent. Through it all he had been a religious seeker, a Christian open to the world’s great traditions, a man of spirit immersed and fluently moving in public life. It became evident that he had experienced both miseries of loneliness and despair and moments of deep mystical insight; evident that he was a man of prayer; evident, too, that he had had a rigorous practice, assembled not by keeping company with a living teacher (Schweitzer is the exception) but by sensitive assimilation of written teachings and by the heat and trial and error of daily experience. Devoted to the Gospels and to Psalms, he was a disciple of Meister Eckhart, the medieval mystic and teacher “from whom God hid nothing.” He knew the Taoist and Confucian classics if not by heart, then in heart. He was a thoroughly mindful person—he called the practice “conscious self-scrutiny” from moment to moment. It was the basis for scorching honesty with himself: “You listen badly, and you read even worse,” he once recorded in his private journal. “Except when the talk or the book is about yourself. Then you pay careful attention. Are you so observant of yourself?” But because he saw the nonsense for what it is and didn’t refuse to know, he could also find his way to astonishing terrain: “Each day the first day: each day a life. Each morning we must hold out the chalice of our being to receive, to carry, and give back. It must be held out empty—for the past must only be reflected in its polish, its shape, its capacity.” And to terrain still more astonishing, known to the great mystics of every time and place: “The ‘mystical experience.’ Always here and now—in that freedom which is one with distance, in that stillness which is born of silence. But—this is a freedom in the midst of action, a stillness in the midst of other human beings. The mystery is a constant reality to him who, in this world, is free from self-concern, a reality that grows peaceful and mature before the receptive attention of assent.” To this he added closing words that may be the most quoted in Markings: “In our era, the road to holiness necessarily passes through the world of action.”

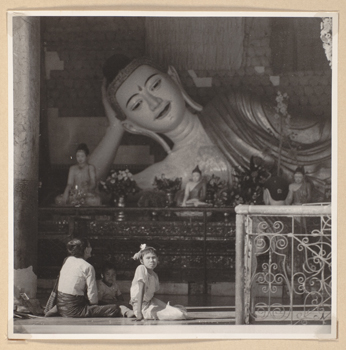

Hammarskjöld’s personal acquaintance with the inner reality of stillness and awe made him naturally receptive to Buddhism. He wrote, “The ultimate experience is the same for all.” Much the same was said by the monk and author Thomas Merton when he had left his monastery in Kentucky for the last time and was traveling in Buddhist Asia. “Even where there are irreconcilable differences in doctrine and in formulated belief,” Merton wrote, “there may still be great similarities and analogies in the realm of religious experience… On this existential level of experience and of spiritual maturity, it is possible to achieve real and significant contacts and perhaps much more besides.” After a round-the-world trip early in 1956, Hammarskjöld wrote to a friend, “I came home with two unexpected favorite countries—Burma and New Zealand—and a brand-new view of Buddhism as a life- and atmosphere-creating factor. The difficulty of ‘accomplishing’ something seems, after this deep-sea dive, greater than ever—but [greater than ever] also [are] the reasons to stake everything in the effort.”

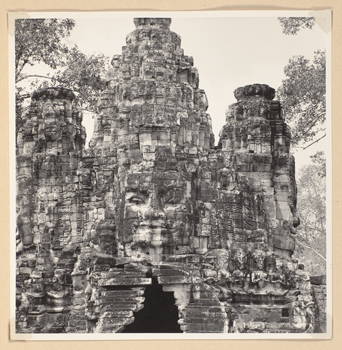

Three years later, after a trip that included time for a flight around Mount Everest and what he called “a day in Arcadia by the upper Mekong in the ancient kingdom of Luang Prabang,” Hammarskjöld wrote: “A great experience. How much more mature and fine the Asiatic art of living is compared to ours. Evidently you have to accept the thought that everything is an illusion before you can master the whole scale of reality with ease, style, seriousness, and happiness. What does it then matter if you are poor, politically inexperienced, or threatened?”

Discussions of religion delighted him. “In one of the capitals of the Orient,” Hammarskjöld reported after a trip to Kathmandu, “—one of the smallest and least accessible ones—I had a conversation, which happened to turn on questions of religion. This happens often in that part of the world.” U Thant, Hammarskjöld’s distinguished successor as UN secretary-general, was a devout Buddhist who later recalled that Hammarskjöld’s “knowledge of Buddhist philosophy was far from superficial, and he was interested in the affinities between Buddhist thought and the writings of Martin Buber. I remember that I tried to straighten him out on the theory of karma.” Hammarskjöld also discussed religion with David Ben-Gurion, prime minister of Israel, and the two discovered a topic of unexpectedly shared interest: Buddhist teachings. Hammarskjöld later sent Ben-Gurion a copy of the English mystical text The Cloud of Unknowing, with a note: “This off-shoot of the great wave of mysticism in early medieval Europe approaches the world of ‘pure being’ to which the Buddhists have sought access from sometimes not too different angles.”

In the winter of 1957, the Room of Quiet opened at the United Nations. A small meditation space on the ground floor of the Secretariat tower, the room was designed by Hammarskjöld in cooperation with the building’s architect and a Swedish artist. A short statement by Hammarskjöld reads: “We all have within us a center of stillness surrounded by silence. This house, dedicated to work and debate in the service of peace, should have one room dedicated to silence in the outward sense and stillness in the inner sense.”