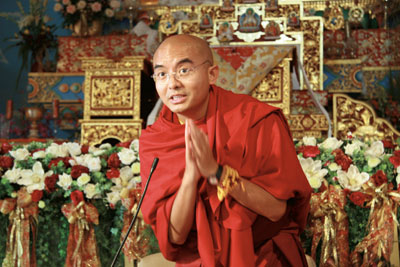

Born in Nepal in 1975, Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche is the youngest son of the eminent meditation master Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, and received the same kind of rigorous training associated with previous generations of Tibetan adepts. In his new book, The Joy of Living(Harmony Books), Mingyur Rinpoche recounts how he used meditation to outgrow a childhood beset by fears and extreme panic attacks. From a very young age, he also displayed a keen interest in science; he has pursued this curiosity and how it relates to Buddhist teachings on the nature of mind through countless conversations with neurologists, physicists, and psychologists. In 2002, he participated in experiments at the Waisman Laboratory for Brain Imaging and Behavior in Wisconsin, to investigate whether long-term meditation practice enhances the brain’s capacity for positive emotions.

In The Joy of Living, Rinpoche’s investigations into the science of happiness are woven into an accessible introduction to Buddhism. Today Mingyur Rinpoche divides his time between Sherab Ling Monastery, in Northern India, and teaching engagements throughout Asia, Europe, and the Americas. I spoke with him this March in California at a program sponsored by the Yongey Buddhist Center.

–Helen Tworkov

What is the value of using scientific technologies to validate the benefits of meditation? If you already have a developed meditation practice, you have no need to rely on science. But science can be useful for understanding the same meaning from a different perspective.

For people engaged in “analytic meditation,” you examine everything that is going on with the mind and you develop trust from reason. For this kind of meditation, every tool is useful. So science can be used as a new tool, a new perspective, a new way of developing trust through reason.

In the West, are we in any danger of diminishing the traditional emphasis on subjective experience and on faith in the teacher by giving so much credibility to external methods? This is not a problem, because in Buddhist practice there’s no gap between outside and inside. So the measurements can be good for Buddhist practitioners. Especially for someone who has no real meditation experience, science can help build certainty about their own practice, help build confidence.

So far, we have seen many “parallels” between science and Buddhism. Can they work in combination? The Dalai Lama said that if the Buddhists and the scientists could join together, it could be of much benefit to the whole world, because the scientists can help find and identify the source of problems with the mind or with the emotions, and the Buddhists have many methods and techniques for solving these problems.

If scientists could manipulate brain chemistry or use genetic engineering to increase happiness, would that be beneficial? Maybe not so beneficial. Because suffering is the cause of happiness.

So the process of transformation is critical? For lasting happiness, yes. Suffering can be transformed into happiness. That is the whole point of my book. Of course, too much suffering is not good. If you become always manipulated by it, if suffering is always the boss, that is not good. And if you have too little suffering, you will not be inspired to pursue real happiness. That is why we speak of “precious human birth.” Because being born in the human body provides just the right amount of suffering that we need in order to transform suffering into a source of wisdom and knowledge.

This morning, in your teaching to new students, you introduced a practice of “resting the mind.” And you said this involved a “secret” that you would tell afterward. Then you demonstrated the posture for this practice, and everyone tried it for a few minutes, after which you revealed the secret: that actually, thisis meditation. So, this “secret,” like the use of scientific data, can be understood as another skillful means. Why do we Westerners seem to require these nontraditional entry points? Buddha said that different beings have different capacities for understanding, different ways of thinking, different personalities and mentalities and cultural attitudes; and that teachings should be in accordance with this. The essence of Buddhism is lovingkindness and compassion and understanding emptiness. And all these different approaches are just many ways of allowing these real, innate qualities to manifest. When we teach, any example that is understood by the teacher and the student can be used. Also, sometimes with people in the West, when they try meditation, they try too hard. They become very tight, their bodies become tense. Everything becomes blocked and difficult. Then they need to learn to relax and to rest the mind—with awareness but not so much tightness.

The interest in science and Buddhism seems to be concentrated on meditation. What about the role of faith, devotion, ritual, acts of kindness or the practice of generosity? Will Westerners have to wait for the scientists to figure out how to “prove” the benefits of these aspects of Buddhism? Many people are doing shamatameditation. This is a kind of resting meditation, also called “calm abiding.” This is good, but in Buddhist training you must go deeper than this. It is important to go deeper into emptiness—not nothingness, but into understanding emptiness as the nature of mind. This is where wisdom and compassion come from. And when you apply the method of this kind of meditation with nonjudgment, then lovingkindness and devotion and faith arise and work together to liberate one from suffering.

A few months ago you inaugurated Tergar Institute in Bodh Gaya, India. “Institute” implies study. Will Tergar encourage the kind of study and practice that you just talked about? Yes. There are three intentions for Tergar Institute. One is to create an international study center where Buddhism can be taught in different languages and people from all over can come for months at a time to study. Another is to bring monks and nuns together for a traditional type of college, or shedra, where they study Buddhist philosophy and train in debate and things like that. Also, an important part of Tergar is to participate in the Kagyü Monlam. This is the big festival at the end of the year where thousands of people gather to pray for world peace. And Tergar will be the residence for the Karmapa and other teachers who come for this.

You come from an extraordinary dharma family, which you describe as very supportive and loving. How do you understand the panic attacks that you suffered from as a child? I cannot say for sure. But being engaged in dharma and growing up in dharma doesn’t mean being completely free from suffering from the beginning. It means to go in the direction that liberates from suffering. So I hope the book shows that this is possible and to share a little bit of how it can be done. That is my wish, my aspiration.