The one thing I have never fully understood about many Buddhists is why they devote so much attention to the individual roots of greed, hatred, and ignorance, yet so little attention to the manifestations of these poisons in social institutions. Is it simply understood that the real work needs to be done on our individual failings, with social greed, hatred, and ignorance being someone else’s problem? Or is it that Buddhists, like so many people, have been deceived into believing that political issues are “none of their business”? Have they been trained to see problems and solutions solely in personal rather than political terms?

The problem is that while we are struggling on an individual basis toward selflessness and compassion, vast systems of economic and political power are working to undermine the process. The astute political commentator H. L. Mencken once observed, “The whole aim of practical politics is to keep the public alarmed (and hence clamorous to be led to safety) by menacing it with an endless series of hobgoblins, all of them imaginary.” Fear and loathing pacify the population, promoting mindless patriotism and obedience. They help justify repressive policies that curtail democratic freedoms and boost centralized power.

But here’s the really bad news: because the corporate system is the quintessence of greed—with corporate bosses legally obliged to maximize profits for shareholders —discussions of the significance, power, and potential of compassion, kindness, and generosity are virtually absent.

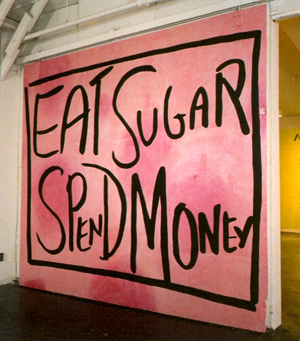

As retailing analyst Victor Lebow explains, “Our enormously productive economy… demands that we make consumption our way of life, that we convert the buying and use of goods into rituals, that we seek spiritual satisfaction, our ego satisfaction, in consumption.” You can’t have people recognizing the piercing pain of desire, the tight agony of pride, the blissful release of generosity and compassion, when you need everyone greedily consuming ever more pleasures, ever more status, ever more things.

When society subordinates its humanity to maximized revenues at minimum cost, then that society is well on the way to becoming lost, falsified, and in fact inhuman. If we are serious about combating selfishness and promoting compassion in the world, then is it not vital that we develop the tools of intellectual self-defense to deal with these assaults on our minds and hearts? The solution must lie in reversing the priorities, in subordinating dead things—money, capital, profits—to life: people, animals, the planet.

But how to communicate this message to the wider world? Part of the task involves challenging the idea that the corporate media are communicating anything approaching an honest view of the world. We have to expose the deep structural biases of the media. Media activism, in essence, is simply an attempt to relieve suffering. Of course we need to practice compassion in individual thoughts and acts—these are the bread and butter of practice, the real test. But where we see political and economic systems guaranteed to generate tragedy and despair, we must also respond to transform and humanize those systems.

But if compassion is the solution, then what role the traditional anger, hatred, even violence, of left progressive politics? What of class warfare? Should we not, for example, be angry with journalists for their role in making the attack on Iraq possible? Should we not be angry that they are facilitating oil-funded global warming skepticism that may make a hell of our children’s lives? If we want to bellow our anger as an indulgence, as a macho badge of commitment—fine. If we want to do something that truly helps the victims of greed and violence to dig up the deepest roots of their misery, then we must try to remain focused on compassion, not anger.

It is no accident that politicians and media commentators focus so much attention on violent incidents, and even angry outbursts, no matter how few they might be in the overall context of peaceful protest. When protestors’ rational arguments are associated with anger and violence, the ideas themselves can be characterized as irrational, emotional and even dangerous. The focus on violence provides a perfect excuse for journalists to avoid engaging with arguments with which they in fact cannot deal, and to marginalize the effort to challenge them.

The antidotes to systemic greed, I am convinced, are political movements motivated by unconditional compassion for suffering. This compassion needs to be rooted in genuinely profound and authentic sources—the kind provided today by the best Buddhist teachers and organizations. I think it is reasonable to accept a kind of “division of labor,” with Buddhists teachers and practitioners working to unearth and make available compassionate resources. Activists should then seek to make the best possible use of these treasures not only by meditating on and developing their own compassionate awareness, but also by seeking to entrench this compassion in supportive systems of political and economic power. Perhaps we can imagine meditators providing the compassionate raw materials and activists working to build the political and economic structures that make possible the further and increased mining of compassionate treasures—a sort of perpetual compassion machine, if you will.

Making People Think

David Edwards is co-editor of Media Lens (www.medialens.org), a UK-based watchdog site that challenges mainstream media reporting. Much of the work of Media Lens involves producing Media Alerts, which are sent out to tens of thousands of subscribers and readers of allied websites. Typically, Media Lens will quote a news bite such as the following from the Guardian writer Martin Woollacott, who wrote in January 2003: “Among those knowledgeable about Iraq there are few, if any, who believe [Saddam Hussein] is not hiding such weapons [of mass destruction]. It is a given.”

Such comments are then contrasted with the views, for example, of former chief U.N. weapons inspector Scott Ritter, who claimed that Iraq had been “fundamentally disarmed” of 90 to 95 percent of its weapons of mass destruction by December 1998. According to Ritter, Iraq represented “zero” threat to America and its allies from 1998 onward.

Media Lens goes on to note that, although highly credible, this view has been virtually ignored by the mass media. It then invites readers to form their own views on the relative merits of the arguments, and to make their views known to journalists and editors via company email addresses. Journalists often reply, and Media Lens includes their replies in further debate and discussion.