While the usually sleepy English village of Chislehurst was being bombarded by German aircraft in the early morning of January 6, 1915, Alan Watts—who was to become one of the foremost interpreters of ancient Eastern wisdom for the modern West—was born to Laurence Wilson Watts and Emily Mary Buchan.

The elder Watts was an executive with the Michelin tire company in London, and his wife taught at a local school for daughters of missionaries to China. It was because of his mother that Alan had early exposure to Asian culture, via art and other gifts brought by parents returning from China. A Sinophile all his life, Alan attributed the start of his interest in the writings of Chinese poets and sages to his mother’s gift of a Chinese translation of the New Testament.

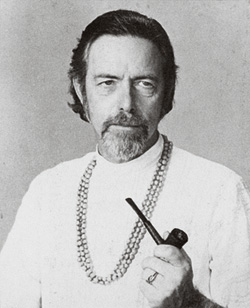

Watts’s spiritual journey began with a bucolic childhood steeped in the cobwebbed mores of Edwardian England. He had a religious upbringing in the Church of England, and by his teens he’d become an expert on ecclesiastical ritual. He took as his early role models local priests who lived large and showed him that one could be worldly and a holy man, too. In later years he described himself as an unabashed sensualist and openly admitted he was ill at ease with people who militantly abstained from smoking, sex, and drinking. “I am committed to the view,” he wrote in his autobiography, “that the whole point and joy of human life is to integrate the spiritual with the material, the mystical with the sensuous, and the altruistic with a kind of proper self-love.”

As much as he respected his native religion, Watts was troubled by its solemn hymns, its rigidity, and the dualism he found in its teachings, although its harshness was tempered by the natural tranquility he found around him in his mother’s garden and surrounding countryside. “I used to lie in bed feeling my spirits raised by the bird symphony, a choir of angels in praise of the sun. And at sunset a solitary thrush would perch at the very top of the rowan tree and go into a solo,” recalled Watts of his youth.

Watts’s mother was overprotective of her only surviving child (she had suffered two miscarriages and an earlier son’s death at just two weeks old); she discouraged Alan from sports and pushed him toward artistic and intellectual pursuits. His father read to him from Rudyard Kipling and spoke of Buddhism, both of which enchanted the boy with “curious exotic and far-off marvels that simply were not to be found in muscular Christianity.” In the evenings Alan joined his parents in the living room, where his mother played an upright piano and his father sang arias from Gilbert and Sullivan. During school holidays he would write heady papers—often on theological subjects—for the fun of exploring his own ideas, and then read them to his parents, launching family discussions that ran long into the night.

In high school Watts considered his Anglican religious education “grim and maudlin though retaining fascination because it had something to do with the basic mysteries of existence.” His view of the universe was forever changed after reading about nirvana in Lafcadio Hearn’s book Gleanings in Buddha-Fields. “Buddhist bells sound deeper than Christian bells,” he later wrote, “. . . and om mane padme hum ran in my brain as something much more interesting than ‘O come let us sing unto the Lord.’” So in 1929, at the age of fourteen, he declared himself a Buddhist and started a correspondence with the most famous English Buddhist, Christmas “Toby” Humphries, a high court judge, Shakespearean scholar, and chairperson of the Buddhist Lodge in London. When Watts, chaperoned by his father, showed up at the Lodge, Humphries and the other members were astonished to learn that their brilliant new associate was a teenager.

Watts became the organization’s secretary at sixteen, the editor of the Lodge’s journal, The Middle Way, at nineteen (a position he held for the next four years), and wrote his first book, The Spirit of Zen, in a month of evenings at the age of twenty. He chose not to attend college, although much later he was made a Harvard research fellow and received an honorary doctorate from the University of Vermont; instead, he designed his own “higher education” curriculum, with Humphries as the preceptor.

In 1983, now all of twenty-three, Watts moved to New York City with his first wife, Eleanor Fuller, a Chicago socialite and practicing Buddhist. Watts and Eleanor studied with the Zen master Sokei-an Sasaki Roshi (1882-1945), who had a temple in a one-room brownstone apartment in the city. Of Sokei-an, Watts said, “I felt that he was basically on the same team as I; that he bridged the spiritual and the earthy, and that he was as humorously earthy as he was spiritually awakened.” Some years later, Watts’s mother-in-law, Ruth Fuller, married Sasaki and became a Buddhist teacher herself.

In 1940, Watts wrote The Meaning of Happiness and started lecturing and writing in earnest to an American audience. His talks were well received by small groups in local bookstores and private homes, but on the whole he felt dismissed as “a crackpot with green idols, thighbone trumpets and cups made from human skulls” adorning his home. In contrast to the openness to Buddhism he had experienced in England, in his early years in the States Watts found himself marginalized by his vocation. And while he would ultimately help popularize Buddhism to a mainstream American audience, he would always remain an iconoclast carving out a new spiritual path through stubborn terrain.

Although Eleanor came from money, Watts felt pressure to be the breadwinner. Interest in his writing and lectures was limited, and he struggled to earn a living, fearing he was on his way to becoming “a misfit and an oddity in Western society.” So at twenty-six, in order to have a steady job, he decided to leave New York and take ordination as an Episcopalian priest at Seabury-Western Theological Seminary in Evanston, Illinois. He later wrote of this move, “I did not then consider myself as being converted to Christianity in the sense that I was abandoning Buddhism or Taoism. The Gospels never appealed to me so deeply as the Tao Te Ching or the Chuang-tzu book. It was simply that the Anglican communion seemed to be the most appropriate context for doing what was in me to do in Western society.”

Though Watts later said of this time in his life that he had deliberately gone “square” and that his gift for “ritual magic” made him more shaman than priest (“priests follow traditions,” he said, “but shamans originate them”), his position as priest gave him the power to do away with the elements of Christian ritual he abhorred. This included personal Christian prayer, which he called a “clumsy encumbrance” that got in the way of the fact that “God is what there is and all that there is.” Watts took a position in 1944 as Episcopal chaplain at Northwestern University, where he threw open the church’s doors and developed a dedicated following of students who came for prayer and stayed for tea, cocktails, and regular late-night discussions. He jazzed up church services by performing “magical liturgies,” banning “corny” hymns, limiting sermons to fifteen minutes or less, and celebrating mass as “a joining with the Cherubim and Seraphim, the Archangels and Angels, in the celestial whoopee of their eternal dance about the Center of the Universe.” Watts had creative ideas about those angels, saying, “When I contemplate such ordinary creatures as pigs, chickens, ducks, lazy cats, sparrows, goldfish, and squids I begin to have irrepressibly odd notions about the true shapes of angels.”

A longtime friend and colleague, the scholar and esteemed religions author Huston Smith said of Watts, “He was a consummate liturgist. We were together once on an Easter Sunday at Esalen [Institute, the renowned alternative education and retreat center]. And at 10 a.m., to a full house in the Huxley room, he sang the Anglican liturgy and he had a beautiful voice. I won’t speculate or probe about his belief in that, but he was from first to last a consummate performer.”

Watts was also a bohemian, a term he defined as someone who “loves color and exuberance, keeps irregular hours, would rather be free than rich, dislikes working for a boss, and has his own code of sexual morals.” His lifestyle went directly against the Church’s mores and those of his wife, who felt that his libertarian views on sexuality (particularly his belief in free love) didn’t make for a solid marriage. In 1949 she left him, taking their two young daughters with her, and had their marriage annulled.

Smith notes that the chaplainship at Northwestern was “too small a puddle for Alan Watts,” and that was surely a factor when in 1950 Watts hung up his robes and left Illinois with one of his students—and former babysitter—Dorothy Dewitt, who became his second wife. The couple moved to a farmhouse in upstate New York, where they lived until 1951, when Watts was offered a faculty post at the newly formed American Academy of Asian Studies in San Francisco (now the California Institute of Integral Studies). Among its students were the future Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Gary Snyder; Richard Price, cofounder of Esalen Institute (Watts was invited as the center’s first speaker); and teachers like the Indian thinker Krishnamurti and the religion professor Frederic Spiegelberg.

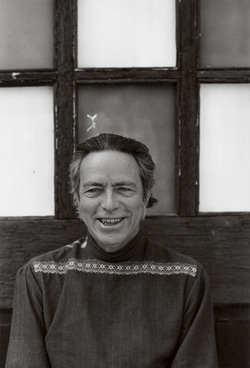

At the American Academy of Asian Studies, Watts was finally in a place he loved, doing what he loved. He could spend all his time engaging in “spiritual mischief” and exploring issues of human identity and the transformation of consciousness. He was free to teach what he liked and utilized techniques ahead of his time, such as mixing disciplines. In a single course students were exposed to Buddhism, Tantric yoga, biophysics, cultural anthropology, cybernetics, and guest speakers who spoke on a number of subjects. Watts believed that “no intelligent person should restrict himself to artificially segregated fields of spiritual or intellectual adventure.”

Watts disdained equally formal education and religious practice and came to the defense of his friend D. T. Suzuki when he wrote: “The uptight school of Western Buddhists who seem to believe that Zen is essentially sitting on your ass for interminable hours (as do some of the Japanese), accused [Suzuki] of giving insufficient emphasis to harsh discipline in the course of attaining satori [awakening].” Watts, like Suzuki, believed that “too much zazen is apt to turn one into a stone Buddha,” and sat only when the “mood” was upon him. Watts supported this belief by quoting the Sixth Zen Patriarch, Hui-neng, who said, “A living man who sits and does not lie down, a dead man who lies down and does not sit. After all, these are just dirty skeletons.”

During the mid-fifties, Watts guest-lectured at Columbia, Yale, Cornell, Cambridge, and Harvard, where he befriended Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert (later Ram Dass), who were conducting their LSD experiments at the time. Although Watts didn’t publicly endorse drug use, he was a mescaline “guinea pig” for Oscar Janiger’s experiments and took LSD as a subject in Keith Ditman’s studies at UCLA. Watts continued to drop acid recreationally through the rest of his life. He was so fond of what he considered its enlightening aspects that he offered each of his children a guided trip when they turned eighteen.

In the spring of 1957, Watts left the Academy of Asian Studies and went out on his own. By then he had also had enough of the “obsolete institution” of marriage and the white picket fence that came with it. He had fallen out of love with Dorothy and left her and their four children.

Watts paid a high price for his personal freedom. During their split-up, Dorothy found she was pregnant with their fifth child. Now, with seven children to support, Watts had to work incessantly. He wrote books (fifteen after 1957), poems, and articles (some for Playboy magazine); created art and music; lectured; and traveled (including trips to Japan and Switzerland, where he spoke at the Carl Jung Institute and met with Jung at his home). Watts took care of his children and never missed a writing deadline, but often did not care for himself. The unrelenting work schedule combined with years of heavy smoking and escalating vodka consumption drained his health and energy. He is reported to have been hospitalized with delerium tremens, a serious condition indicative of late-stage alcoholism.

Watts found a drinking partner in Mary Jane Yates King, known as “Jano,” a journalist and public relations executive who shared Watts’s spiritual, philosophical, and creative interests and whom he described as the soulmate he had been “looking for all down my ages.” They eventually married and stayed together until his death. Apart from their struggles with alcoholism, the couple enjoyed the ideal bohemian lifestyle to which Watts had aspired. They lived in Marin County, California, alternating their time between the Mount Tamalpais bohemian community of Druid Heights and a Sausalito houseboat. Watts attended tony Hollywood parties with fellow guests like Marlon Brando and Anaïs Nin, and shared with Jano a profusion of interesting artistic and intellectual friends.

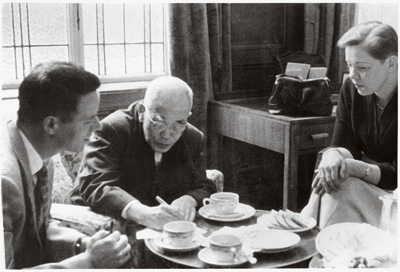

In 1960 Huston Smith arranged for Watts to meet Aldous Huxley at dinner in Cambridge, Massachusetts, when Watts was again lecturing at Harvard and Huxley was a visiting professor at MIT. The two had been at the same social gatherings before but had never conversed. Smith recalls the end of the evening: “I could almost see the wheels in Aldous’s mind sort of sorting things out after Alan left. And then came the verdict, ‘What a curious man. Half monk and half race-course operator.’ I told Alan some time later. Alan loved it and said, ‘He’s got me exactly right.’” Huxley and Watts became close friends.

In 1959 and 1960 Watts taped twenty-six lectures collectively titled “Eastern Wisdom and Modern Life” for National Educational Television, the precursor to the Public Broadcasting System. He traded in the traditional classroom setting of educational shows during that period in favor of a Zen garden; he would arrive at the studio in time for taping and just start talking. His intimate presentation and informal setting won many viewers and brought him a following of non-Buddhists across the United States. Watts gained such a devoted following, Smith recalls him once saying that he could have opened his own monastery in California “because he was so charismatic and turned on crowds.”

All along Watts disdained the role of yogi or Zen master, although he understood the desire of some people to have one. To him it was just another ego trap, and he discouraged his close students from treating him as such. Instead, he encouraged them to become his friends once he felt he had taught them sufficiently. Of a friend who disappeared to India to seek enlightenment, he wrote, “I miss him. I wish I could show him that what he is looking for is not in India but in himself, and obvious for all to see. But he will not believe me because I am not a guru, and all gurus represent an endless ‘come-on’ where ‘veil after veil shall lift, but there must be veil upon veil behind’ until they bring us by our own desperation to absolute surrender.”

Throughout the sixties, Watts and Jano embraced the burgeoning counterculture movement of which Watts was one of the heroes. His work was a magnet for a generation looking for meaning and trying to define themselves and a new society. What many baby boomers today know of Buddhist ideas they learned from Watts’s work, and it is unlikely that Buddhism would have gained the popularity it did in the U.S. without his presence. “Alan Watts and Suzuki Roshi were the two people writing about Zen in the 1960s,” says American Zen teacher Roshi Bernie Glassman. “Anyone who was around then and interested in Buddhism would have been influenced by Alan Watts.”

In the end, Watts lived a life bound by no rules save his own. At the conclusion of his autobiography, In My Own Way, published in 1972—a year before he died—he wrote, “As I look back I could be inclined to feel that I have lived a sloppy, inconsiderate, wasteful, cowardly, and undisciplined life, only getting away with it by having a certain charm and a big gift of the gab. . . . A realistic look at myself, aged fifty-seven, tells me if I am that, that’s what I am, and shall doubtless continue to be. I myself and my friends and my family are going to have to put up with it, just as they put up with the rain.”

Regardless of how modestly—and uninhibitedly—he may have viewed himself, Watts had profound insights into the nature of life and existence that have affected millions of people. “My point was, and has continued to be, that the Big Realization . . . is not a future attainment but a present fact, that this now-moment is eternity and that one must see it now or never,” he said.

Watts’s death from heart failure on November 16, 1973, at age fifty-eight, at his home at Druid Heights was as unorthodox as his life. Hours after he died, but before authorities could get involved, Jano had him cremated on a wood pyre at a nearby beach by Buddhist monks. Although public cremation is illegal, no charges were brought.

After Watts died, Gary Snyder (whom Watts once famously said he would have liked to claim as his spiritual successor) wrote this “Epitaph for Alan Watts”:

He blazed out the new path for all of us and came back and made it clear. Explored the side canyons and deer trails, and investigated cliffs and thickets.

Many guides would have us travel single file, like mules in a pack train, and never leave the trail. Alan taught us to move forward like the breeze, tasting the berries, greeting the blue jays, learning and loving the whole terrain.