We had just opened our building in lower Manhattan when we saw smoke sliding out from under Rooster Vargas’s door. My then supervisor, a sultry woman in her mid-twenties who did not know what she was getting into (and who soon became conveniently pregnant and left), pounded on Rooster’s door. She got no response. She barged into his room with a fire extinguisher so shiny and immaculate it resembled a religious object.

We found a chicken defrosting under a scalding shower. Rooster had gone shopping.

Seven years have since past. Rooster’s residence is without Rooster. After interminably shooting up, snorting, tormenting staff, inflicting on other residents his bug-laden cart that clung to him like a second body, Rooster was evicted. I am still a case manager at the forty-four-unit independent housing facility run by my agency for people who are mentally ill (there are also rooms for people who are handicapped, either physically or financially).

My Buddhist friends are impressed by the work I do. Such easy access to the First Noble Truth. They have a point. Reggie, the resident with whom I have worked the longest, is schizophrenic, a bilateral amputee, and has AIDS. He lost his legs to frostbite. Before he lost his legs, he lost his toes. The Voices, in both cases, ordered him to sleep in an abandoned garage, open to the cold, the wind, the icy rain. As to how he got AIDS, Reggie has no idea.

I accompany Reggie to his clinic appointments. I have his doctor write down for me his T-cell count (bad and getting worse). An affable recluse, Reggie greets strangers with the causeless heartiness so disconcerting to New Yorkers.

Going anywhere with Reggie means waiting: waiting to be seen, waiting to be taken home by ambulette after being seen. Reggie ticks his head as he waits. I try to meditate. But encountering clotted time head-on sometimes throws me off balance. I will forget for a moment all that I have learned about working with obstacles. The waiting room has the feel of a sinister box in which we are all trapped. A dead space, I grouse.

Parked beside me, Reggie sits and says nothing. I straighten my back. The brand name of his wheelchair catches my eye: Quickie. I smile and draw a breath.

A case manager’s job at a residence like mine, where just about everyone is crisis-prone, is a little like helping with the oars on boats racing toward choppy waters, or in reverse. We try to hook our clients up with day programs and therapists, with Section 8, the federal program that pays roughly two-thirds of the bottom-end renters’ rent. With few exceptions, our residents are on SSI (Supplemental Security Income), SSD (Social Security Disability), or PA (Public Assistance).

There ought to be a course given in listening-training for prospective case managers, but there isn’t. Words sometimes fly at us from deep, dark wells that have been poisoned many times over. They sting, burrow, burn. I receive health and dental benefits, plus a small salary, for turning my ears into landing strips so the words won’t crash.

Aaron, the Tibetan Buddhist in 5F, visits me before starting his day. “I feel porous,” he laments on bad days. “Like there is nothing inside of me. I feel empty.”

Aaron does not mean empty in the Buddhist sense of fullness of being inherent in the absence of self. He means feeling plundered of flesh and bone. Aaron is on a high dosage of Clozaril, a relatively new, potent, reputedly effective antipsychotic drug.

“Mornings are always hard for you,” I remind him. “But by the afternoon, you feel you have your body back.”

“My problem is self-cherishing,” he complains. I laugh. Aaron has found in the tractates of the lamas exactly the medicine he does not need.

“Aaron, you don’t cherish yourself at all. Not even a little bit. Your problem is the opposite.”

Aaron disagrees. He is almost forty, but his large, sleepy eyes shine with devastating innocence. His mother died when he was three. He expects each of us to provide pieces of her, tiny bits of resurrection.

I was once with Aaron in a little room in Payne Whitney Emergency. “I am in hell!” he kept screaming. Each time he screamed, the little room got smaller.

Finally he cried out, “Robert, hold me!” I held him. His screaming stopped. His body shuddered into a prone position on the couch. He dozed off. Through my bony hands, he had lured his mother into the room.

During our weekly staff meetings, problematic residents are discussed (these can be long meetings). There is always someone who has gone off his or her meds, someone who is aggressive or delusional or maybe both. Then, there is the resident with the drug problem, the resident in rent arrears, the resident who has bestowed a sexually transmitted disease upon another resident.

There is not much we can do to solve any of these problems, beyond attempts at persuasion, careful attention, and in rare cases, police action or eviction. Our residents sign leases. They are New York City renters. They can have over whoever they wish. (The aforementioned Rooster once had as his guests two dying pigeons, while Melissa entertained a famous feminist author she met in a psych ward.)

This laid-back approach can be frustrating. There once lived in our building an old black woman from Florida named Grace. Grace suffered from breast cancer. She called her tumor “the frog.” When she was in pain, she would say, “The frog is cooking.”

Staff recommended surgery. Grace refused. She regarded surgeons as assassins. After explaining radiation to her, I suggested that. It sounded fine to her.

At the hospital, Grace tried to smoke in the examination room. The doctors were charmed and horrified. The notion of radiation was briefly entertained, then brusquely shot down. The blade won out.

“Grace doesn’t want surgery,” I insisted.

“She is not mentally competent,” a doctor retorted.

For days, my anger toward that doctor was as heavy inside me as Grace’s frog. It walked with me to work. It sat with me as I scanned the blue face of my computer screen. Then, it was gone. I was left with a hollow feeling worse than the anger. I could think of nothing more to do for her.

A year later, I succeeded in borrowing a Baptist minister from a hospice. He had a folksy smile, but a ferocious pastoral handshake, perhaps more the result of nervousness than inspiration.

“Reverend, you are killing me!” Grace cried out.

The pastor apologized. Grace shot me a savage look for bringing him. He invited the dying woman, whom the blade never touched, to join him in prayer. She would have no part of it.

Toward the end of the day, when all is quiet, I sneak in a few mindful breaths at my desk. Breath as refuge. Not from my work, from which I derive tremendous satisfaction. The eight residents on my caseload, minus one, are unaccountably kind and cooperative. Even Carlos, my drug abuser, who is nearing sixty, often flashes a benign smile that borders on the cherubic, when lying to me about whether or not he’s been using.

The problem is the subversive energy that lurks beneath the social worker’s good works. When mindful, one’s energy does not have to run amok. In fact, the failures intrinsic to the job often assure that it does not. But let Li Ping praise me for my help in getting her her citizenship, or Aaron liken me to Milarepa for getting the super to fix the leak in his toilet tank, and I may find myself with a fugitive buzz that spreads through my body like a pleasant fever.

This year, for my birthday, Li Ping gave me a glazed Buddha. It is all girth and mirth, but Li Ping assures me he will help me with my meditation. It sits on my floor at home near where I sit. I have yet to bond with it. But I have bonded with Li Ping.

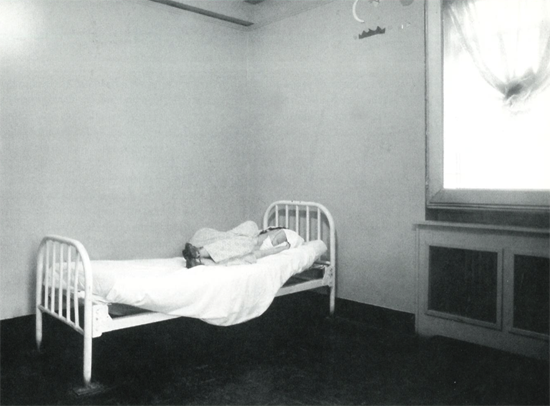

I first met her eight years ago, when she was living at one of the group homes my agency runs. I was doing rounds one night and found her curled up on the couch, talking to herself in Cantonese. Her eyes were silent, empty.

Now when four o’clock rolls around, I open my office door and wait for Li Ping’s visit. She enters, slightly breathless, laden with charity requests (Li Ping has a disquieting propensity for lavish charity-giving), eager to talk. She likes to talk about her student days in South China. Or, more precisely, about her days with the student work brigades, harvesting rice. Her reminiscences take on the plump cadences of satisfaction. (It was marriage in America that caused her life to fracture, not the Chinese Cultural Revolution.)

“Some students suffer from bee bites, you know, and I have to help them be calm and find cream.”

“Were you ever bitten?” I ask.

“Me? Never!

“And others, you know, get dizzy and fall down in the field. I have to find water for them.”

“Didn’t you ever fall down in the field?” I ask.

“Me? Never! I am strong!” She laughs.

I feel China tipping into my lap. I join Li Ping in her laughter.