How did the world come into being? A cosmic egg, a pair of primal twins, a primordial fog that separates into earth, sky, water…. Years ago I learned that, though there are thousands of different creation myths, they tend to fall into the same handful of patterns.

How did you come to Buddhist practice? Here, too, the myriad stories tend to fall into a handful of patterns: there’s the childhood wound, the remarkable coincidence, the long malaise, the sudden unsought joy….

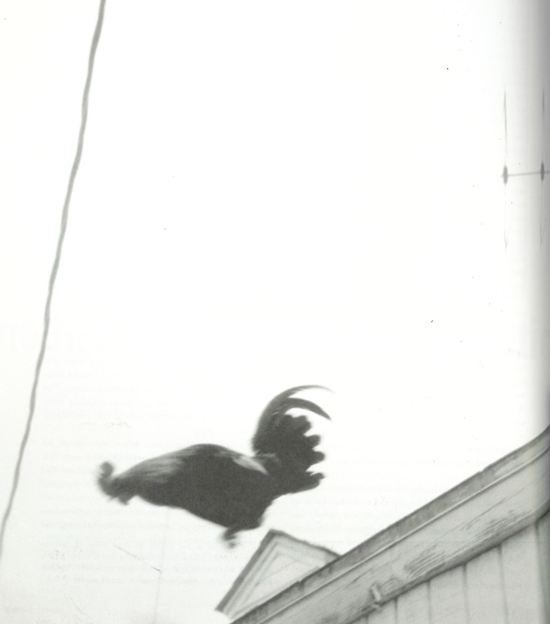

In telling my own story, though I could enter by anyone of these gates, I prefer to start with the last on the list because it seems to me the most timeless and most true. From the time I was quite young, I felt susceptible to a certain kind of joy that seemed to come from nowhere. It was very quiet, not earthshaking, but when it happened, it utterly altered the atmosphere. One of the first times I experienced it was in a tiny village in Brittany my family was visiting. The village was in the region of Finistère (“Land’s End”), once believed to be the very edge of the flat earth. On the foggy afternoon that we arrived and went to stand on the beach, I felt permeated by a powerful and ancient fear. This was the place where the devil was said to have leapt off the earth into the endless sea, a place that for centuries had represented the human terror of being nowhere, of facing the unknown. That night I fell fitfully asleep in the little farmhouse hotel where we had rented a room. In ‘the morning, just at dawn, a rooster crowed. Hearing the sound, I experienced that everything around me—my parents sleeping in their bed, the glass of water on the window sill, the green grass outside in the pink light of sunrise, the waves crashing beyond—was in the right place, at the right time.

Years later, sitting sesshin at the Rochester Zen Center, I heard Roshi Kapleau’s voice in the zendo, addressing the human terror of facing the unknown. Remember that you can’t fall off the earth, he said, and there I was—back at Land’s End, hearing the rooster crow.

But I am getting ahead of myself. . .

There were these moments of quiet joy. I believe they come to everyone. Once I heard a man describe the day when, as a boy in school, he looked up and noticed the motes of dust glistening in a shaft of sunlight. He was responding to the question How did you come to practice? What I don’t understand is why, for some of us, these moments—quiet and evanescent as they are—become gateways.

I only know that these moments, saved one by one like jewels in a box, began over the years to exert a powerful pressure on me. Though they had been moments of a deep and peaceful joy, they began collectively to make me suffer. They were so rare and came so unbidden—like windfall, or shooting stars. I didn’t know how to make them come, to make them last, or link them together. By the time I was a teenager, I felt they wanted something of me—but I didn’t know what. I felt they held the key to the meaning of life, yet they just lay there, shining in a box.

Early in my first year of college, the tension became unbearable. I’d grown up going to Mass with my Jewish father (who’d become a Christian shortly before my birth) and, though I was feeling increasingly estranged from my Catholic roots, I didn’t know where else to turn. One day I leapt on my bicycle and rode, as fast as I could, through the campus and its surrounding cornfields, to the rectory. I pounded on the door for a long time, until at last a scowling woman came and opened it a crack. “I need to see a priest,” I told her. “The rectory is closed today,” she said, and shut the door in my face. I rode home through the cornfields feeling so desperate that, if there’d been a cliff anywhere in that flat part of Ohio, I might have thrown myself over it.

And here, already, several gates converge: the sudden joy, the long malaise, the coincidence. For it does seem a remarkable coincidence that—barely a week after I’d felt the door of my childhood religion slam in my face—a young monk from Thailand came to the college and began offering a class in meditation. His instructions were very simple: cross your legs, keep your back gently straight, focus on your breath as it leaves the nostrils. . . . At the end of the first session—which lasted only twenty minutes—I knew that I had found what I’d been looking for, with increasing desperation, for so long.

On my way back to the dorm, I walked through the student center, where a group of young men were playing a game of pool. A bright wooden ball came flying off the green table, across the room—and into my hand. I just opened my palm, as I was walking by, and the ball flew into my hand.

YES! Following my breath, I had found my way to where the rooster crowed, and everywhere I went was the right place at the right time. I climbed the stairs to my room under the eaves, and when I walked in the door the first thing I saw was a tiny art-gum eraser sitting in a pool of light. It was absolutely luminous.

Now, remembering those moments, there’s a part of me that wants to let loose with a wild crone-cackle.Trickster path! I want to say. You were on your very best behavior, weren’t you? Like a suitor. You lured me with such beautiful gifts, you made it seem so easy. I could cross my legs and follow my exhalations for twenty minutes, and the world would fly into the palm of my hand. The smallest and most humble thing I encountered—a bit of brown rubber—would turn into a jewel before my eyes.

Little did I know what awaited….

For a month I sat with the monk from Thailand in a college basement in Ohio. When it was time for him to leave, I felt bereft. “Where should I go next?” I asked. He wrote on a paper napkin, “Karme Choling.”

The end of the school year came, and I made my way to Barnet, Vermont, for a meditation retreat. To me, “retreat” meant a communal gathering, and I was stunned when they hitched me and my red-and-purple zafu to the back of a tractor and deposited me in a hut at the top of a lonely hill. Though it was summer, it began to rain hard. I couldn’t get the wood stove going and the kerosene lantern filled the air with fumes. I sat in the dark, damp and shivering, terrified of the mouse that lived under the bed. When the time came to an end, I trudged down the hill, had what Ic felt to be a hero’s cup of tea, and begged a ride to the bus station to make my way home. Not far from Barnet, the bus broke down and had to be towed. I remember waiting for hours in a drizzle by the side of the road until another bus came to the rescue. For years thereafter, whenever I tried to make my way home from a period of intensive practice, whatever vehicle I was traveling in—bus, car, train, plane—would suffer some form of breakdown. Again and again, just as I was fleeing toward some fervently imagined reward, I would find myself stuck in a place where I had utterly no desire to be.

Trickster path: little did I know where you would lead….

From college I went to graduate school to study philosophy at the University of Toronto. Though I sat regularly with the dharmadhatu there, I had difficulty bringing together the mind of practice with the world of academic philosophy. Late one evening, I was leaving the library late at night, having just completed a draft for one of my professors on “The Buddhist Concept of Non-Attachment.” I’d been working on it for weeks, and was feeling quite pleased with myself—but when I got back to my room, I didn’t have the draft. It was after midnight, and too late to go back to the library. I knew my predicament was hilarious, but I couldn’t laugh. The anxiety that engulfed me was close to panic and came in waves throughoUt the night. The next morning I woke up exhausted, but very clear: I had to leave graduate school. The gap between what I was thinking and what I was capable of actually living was too big.

Someone had told me about an intense and eccentric woman teacher who had a Zen monastery called Shasta Abbey in northern California. I made my way across the country to enter their one-hundred-day training program, which was my initiation to Zen. From there I returned to the East Coast and practiced for some years at the Rochester Zen Center, before settling at last in northern California.

If I say trickster path, it’s not only because I had no idea where it would lead me geographically, but because I had no idea how hard it would be. I don’t want to go on about the difficulty, because anyone who has truly engaged with the practice knows what must be faced: the amazing ingenuity of the monkey-mind in its capacity for distraction; the intensity of fear and anger; the layers and layers of grief—not simply for one’s own private collection of hurts but for the vast reservoir of human sorrow; the horror at the human capacity for evil. At one point, I became so obsessed with the Holocaust that for weeks I couldn’t swallow without gagging. I might have gone off the deep end if a kind monk hadn’t given me the very book I needed to read: And There Was Light, the autobiography of Jacques Lusseyran, a survivor of Buchenwald. The apparition of just the right help, at just the right time, has been a recurrent theme throughout my years of practice—ever since the monk from Thailand arrived, wrapped in his orange robes, and taught me how to meditate in that basement in Ohio.

Whatever difficulty I may have encountered, the practice has been the medium of the greatest happiness, the truest strength, and the deepest friendships I have ever known.

Still, I would not be honest if I did not acknowledge that in recent years I’ve experienced profound disillusionment. I’ve discovered that there is something much more obdurate about the human personality than I have ever wanted to believe, and at times I have despaired at what has seemed to me the persistence of the childhood wound—my own, my companions’, and yes, my teachers’. In this last regard, the disillusionment is still so recent and so raw that I can’t provide a resounding resolution or epiphany. Yet lately, just lately, a certain image has been coming through to me like the sound of a horn through dense fog:

As a child, I loved the game you play by making different shapes with your hands: rock, paper, scissors. I especially loved the moment when “paper” covered “rock.” I was enchanted with the idea that something as soft and pliable as paper could conquer something as hard as rock. But then there was always that painful moment when scissors cut into paper…. The game could never end, because no one shape was invulnerable. When I discovered meditation, it was as though I discovered the “shape” that could rise to meet any obstacle. Following the breath, working with a koan: no matter how difficult, it seemed that there was no pain, no doubt, the practice could not penetrate. Then I experienced what, sooner or later, happens to many long-term practitioners. In some form or another, for one reason or another, one undergoes profound disillusionment within the context of practice. This engenders a truly radical feeling of betrayal, an intense existential nausea. The place where one went to find release from suffering has itself become the source of acute suffering.

Where is the shape that can meet this rock?

I can’t see it yet, but I’m beginning to understand what’s obstructing my vision. It’s a faulty sense of where “the place” disappears. I think of all those times when the bus, the car, the train broke down. Again and again, the trickster-path was telling me, “Think you can get away from me? Here I am!” He lured me with his jewel-moments, my beautiful groom, my impossibly demanding husband, and now he’s really gone too far. He’s taken me to the very edge. And there—through the din of my still turbulent emotions—I hear him telling me: The earth is round, the practice has no end. ▼