Maruyama, Japan, March 3, 1990

I received a call from Isabel, who had been with Katagiri the night before he died. She and another disciple of his, a male nurse, had turned him over the night before. One of his feet was cold. They knew he didn’t have long when they felt the cold foot.

“I remember once he said, ‘When the time comes to die, just die.’ But he didn’t want to die,” she said. “He hung on and changed his diet and took all the treatments. He didn’t give up till the very end. And then he followed his own advice beautifully.”

Tomoe-san, his widow, was exhausted and grieving, but surrounded by friends, fellow students, and family. Preparations for the funeral were underway. Nishiki would fly over to conduct it. Calls and cards were coming in from all over the Buddhist world.

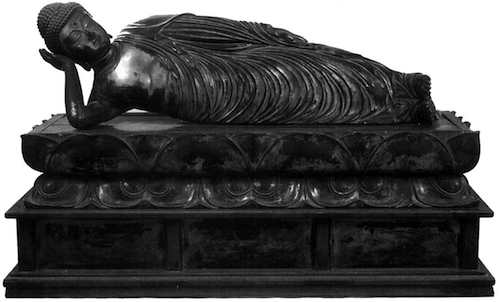

All the disciples and both his grown sons gathered around Katagiri’s body on the morning of his death. Isabel guided the others in washing the body and preparing it so that fluids would not leak from his orifices. Tomoe-san rubbed his skin with a lotion. Isabel said his body was beautiful, youthful, and lovely in color. Chanting at each transition, they dressed him in his best robes, carried him downstairs, put him in his coffin, and lit incense.

She said that at the altar in her room she had offered him a tiny bowl of broken incense bits. When Katagiri was five or six, she explained, he had admired the priest who used to come to his house to do services, and decided that he wanted to be a priest too. He started sneaking all the broken and burnt-down stubs of incense sticks. He kept them in his pockets and would snack on them during the day.

For a couple of weeks before he died, people had been flying and driving in from all over and sitting zazen downstairs below his room. His body remained there the standard three days before cremation. Even though the winter was cold, the house was warm, and techniques of preservation were therefore especially important. At that time of the year [March] in Minneapolis the demand for ice packs was nil. The stores were out. So Isabel had to improvise. As a result, Katagiri’s body, which was covered with flowers and herbs, lay in state in his simple casket on a bed of frozen bags of Birds Eye Tiny Tender Peas.

Isabel told me about the funeral. It had been held six weeks after Katagiri’s death. She’d wanted me to come, but it was too far and too expensive. Norman was there. All sorts of high mucky-muck roshi from the Soto-shu in brocade robes came and there were endless testimonials to Katagiri’s teaching from students and teachers alike. This was in stark contrast to [Shunryu] Suzuki’s funeral, to which no one from the Soto-shu came except for his old buddy Niwa Roshi. I almost got the impression Isabel liked it better when they’d written us off. But then she said she was moved by the ceremony—she realized what a bridge Katagiri had been to help bring together two worlds so far apart. She said that Katagiri’s body hadn’t been left unattended for a moment since well before he died until he was cremated. The funeral home was completely responsive and let Katagiri’s disciples tend to his body as they saw fit. She took the ashes out of the oven and personally ground the bones as per law and divided them into five equal parts destined for the Minnesota monastery of Hokyoji, the Minnesota Zen Meditation Center, Tassajara, his wife Tomoe, and his home temple of Taizoin in Japan.

Nishiki had given an eloquent and poetic talk at the funeral, which Shuko translated. I’m sure it was moving, but I couldn’t help but think how neat it would have been, in addition, to have played back some of Katagiri’s own talks.

When the time comes for you to face death, you have to return to the very first moment of death. . . . We should practice this again and again. We have to return to the silent source of our life and stand up there. We have to come back to the realm of oneness and make it alive, with a feeling of togetherness with all sentient beings and a deep understanding of human suffering.