Bodh Gaya is Buddhism’s Mecca, Vatican, and Wailing Wall. Among the eight great Buddhist pilgrimage sites in India, Bodh Gaya is the most visited. But unlike the holy places of those other faiths, the great center of the Buddhist world revolves around not a building or a shrine but a single living tree.

For six years the seeker Gautama, hoping to find a way out of suffering, had practiced and painful austerities along the nearby Niranjana River. But finally realizing this was not the path to ultimate happiness, he wrapped himself in a yellow shroud taken off a corpse marked for cremation and accepted a bowl of rice milk from a young village girl named Sujata. This strengthened him. Taking fresh green grass for a mat, he then sat facing east under a local pipal tree and vowed not to rise until he had attained enlightenment.

As he sat deep in meditation, the persistent delusions of his own mind tried relentlessly to distract him. In response, Gautama touched the Earth, calling her to bear witness to the countless lifetimes of virtuous actions that had brought him to this moment. Ultimately his power of compassion and commitment subdued and transformed his inner obstacles, and he triumphed over them to achieve unconditioned bliss.

For the seven days following his awakening, Buddha continued to sit motionless under that tree. He passed another week walking in meditation near the tree, and a third close to the tree contemplating what had happened to him and what he would do about it.

For hundreds of years following Buddha’s death, the only symbols used to represent him graphically were footprints and the pipal tree. A sapling from the original plant was taken to Sri Lanka by Emperor Ashoka’s daughter in the third century B.C.E. When the original tree died in 620, a cutting of the newer tree was brought back to Bodh Gaya. All Buddhists see the tree as a reminder of Buddha’s enlightenment and an inspiration for the ultimate potential that lies within everyone.

Throughout the year, but mainly during the cooler winter months, thousands of monks, nuns, and lay practitioners from all over the world gather to venerate the Bodhi tree now five generations removed from the one under which the Blissful One sat. They rock gently to the rhythm of ancient mantras from Tibet, Thailand, Japan, Burma, Korea, Viet Nam, Sri Lanka, China, and India. Cymbals clash, wooden clappers knock, haunting long horns announce the arrival of important lamas. Sparkling butter lamps compete with bougainvillea blossoms by day and the stars at night. Pilgrims circumambulate the site— some in silent walking meditation, others chanting or spinning prayer wheels or carrying incense. Some stop after each step to prostrate fully on the wide white marble walkway. Hindi film music wafts down from the shops above the holy complex, competing with the horns of buses and screeching motor scooters.

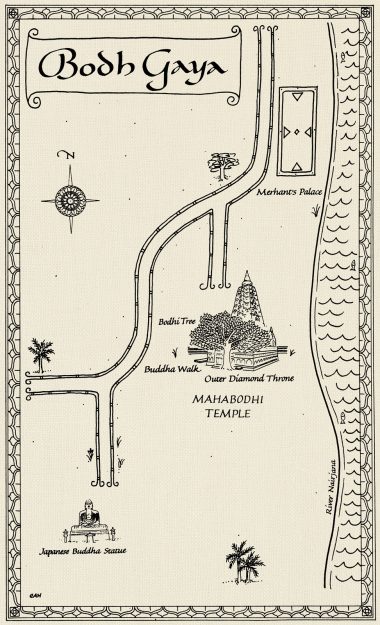

The 1,400-year-old Maha Bodhi Temple, recently declared a world heritage site by the U.N., stands east of the Bodhi tree and towers 180 feet over the glittering roofs of other Buddhist temples representing sanghas from various Asian countries. It rises as a slender pyramid with a cylindrical apex, four towers adorning its four corners. Its courtyard is studded with a large number and variety of stupas and Buddha images.

The Maha Bodhi Temple was rediscovered in 1875 when the archaeologist Alexander Cunningham happened on its top portion gently jutting out of the earth. Parts of the ancient railings surrounding it are from the third century B.C.E. On the altar of the main sanctum is a colossal and ancient golden image of Buddha sitting with his right hand touching the earth. The statue was made from black stone, but for centuries pilgrims have been gilding it.

In 1891, a Sri Lankan monk, Anagarika Dhammapala, founded the Maha Bodhi Society and sought to gain control of the Mahabodhi temple from a local Hindu landowner and to restore it as a Buddhist shrine. After sixty subsequent years of judicial wrangling, Buddhists were given a voice in its management. But still today, more than a century later, Buddhists remain a minority on the Bodh Gaya Temple Management Committee, denied the authority to make decisions about their own temple.

The nearby Archaeological Museum houses relics from the temple as well as objects excavated nearby. The library across the road at the Maha Bodhi Society is worth a visit. Nearby, about six kilometers away up on a hill, is the Mahakala or Pragbodhi caves, where the Buddha spent much of his ascetic life before his enlightenment. The caves at Barabar and Nagarjuni hills, 25 kilometers north of Gaya by road, are some of India’s earliest rock-cut caves, mentioned in the Hindu epic the Mahabharata.

Beyond the temple complex, the town of Bodh Gaya pulses with modern life, cashing in on the parade of pilgrims and needs of the local Indian community that supports them. The market is a vibrant medley of fruit, vegetable, and grains enlivened by hordes of children, beggars, villagers, Asian pilgrims, Western pilgrims and sightseers, monks and nuns in robes of various colors.

Expecting a discreet domicile of dharma, a pilgrim may at first be challenged by the squalor, noise, and confusion of Bodh Gaya, a dharma Disneyland. How ironic that the noisy, bustling streetscapes evolved from commemorating an act of private and silent contemplation under the serene and simple protection of a tree. Surely, the mind exclaims, a zone of peace should be created here, loudspeakers banned, motor traffic rerouted, and littering outlawed!

But the Western visitor may try considering how differently pilgrims from other cultures celebrate their moment in the greatest shrine of their faith. Many have saved resources their whole lives to travel thousands of miles to spend one day here. It is a joyous and ecstatic moment for them, and they seem pleased by the sights, sounds, and smells that mark their moment in the holy land.

After eight visits, I realize it is a great challenge to let go of irritation at all the seemingly inappropriate discordance, but I also know accepting Bodh Gaya as it is demonstrates greater devotion to what the Buddha taught. Bodh Gaya turns out to be an apt metaphor for the contradictions within Buddhism itself: to be in the world but not of it, to live fully but without attachment, to care for others but be true to oneself, and to be happy in a world of suffering.

***

Getting There

The Patna airport is 110 kilometers away. Bodh Gaya also has its own new airport with limited service, but in the future airlines may provide direct flights from New Delhi as well as connecting service to Sarnath (Varanasi), and Kushinagar (Gorakhpur). Bus or car and driver services are available from Patna to Bodh Gaya.

The nearest railway station is about 16 kilometers away, in Gaya, and is on the main railway line between New Delhi and Calcutta. The most popular train from New Delhi is the Poorva Express, which leaves in the evening and arrives the morning of the following day. Motorized three-wheeler rickshaws connect Bodh Gaya with Gaya.

Bodh Gaya has only two major hotels: Lotus Nikko Hotel and the newer Hotel Royal Residency. The Royal Residency offers the best and perhaps only tourist-safe food in Bodh Gaya. For budget travelers, the Japanese Daijokyo Buddhist Temple next to the 80-foot Buddhist statue has simple and clean accommodations.

Courses and retreats in Buddhism take place mainly from November to early February. The Root Institute, on the edge of Bodh Gaya, offers a variety of programs. Insight Meditation conducts annual meditation retreats with Christopher Titmuss, and courses are also run by several of the monasteries in the area.