Lin Jensen is hard to disagree with. If his previous book, Pavement, in which he chronicles his search for peace on city streets, was an ode to activism, Deep Down Things: The Earth in Celebration and Dismay(Wisdom Publications, 2010, $15.95 paper, 176 pp.), his latest, is a tribute to what is buried underneath those streets, and to the life that grows between the sidewalk’s cracks. In Deep Down Things, Jensen’s writing takes on the quality of his subject: our living earth. Here, as in an old-growth forest, where individual trees fall to create gaps in the canopy, Jensen’s musings allow light to penetrate and support the understory. The understory in this small book is the environment—dirt, rain, wind, and root—and how we humans are bonded to it. Jensen considers this relationship from a perspective informed by the insights of deep ecology and his Buddhist background. A natural storyteller, he is at his best when he’s sharing bits of his own experience to demonstrate the dynamic between person and place, inner mind and outer space. He tells us of the Belgian draft horse named Bill who gave him his first glimpse of “the world of wide identification,” and he recounts the memory of losing his family’s farm to developers in Southern California’s Orange County. Spirit, he seems to suggest, is what takes place when the human-earth dynamic is realized.

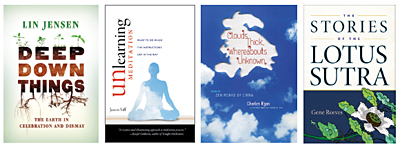

Lin Jensen is hard to disagree with. If his previous book, Pavement, in which he chronicles his search for peace on city streets, was an ode to activism, Deep Down Things: The Earth in Celebration and Dismay(Wisdom Publications, 2010, $15.95 paper, 176 pp.), his latest, is a tribute to what is buried underneath those streets, and to the life that grows between the sidewalk’s cracks. In Deep Down Things, Jensen’s writing takes on the quality of his subject: our living earth. Here, as in an old-growth forest, where individual trees fall to create gaps in the canopy, Jensen’s musings allow light to penetrate and support the understory. The understory in this small book is the environment—dirt, rain, wind, and root—and how we humans are bonded to it. Jensen considers this relationship from a perspective informed by the insights of deep ecology and his Buddhist background. A natural storyteller, he is at his best when he’s sharing bits of his own experience to demonstrate the dynamic between person and place, inner mind and outer space. He tells us of the Belgian draft horse named Bill who gave him his first glimpse of “the world of wide identification,” and he recounts the memory of losing his family’s farm to developers in Southern California’s Orange County. Spirit, he seems to suggest, is what takes place when the human-earth dynamic is realized.

Why does meditation have to be so hard? According to Jason Siff, there is an inherent tension in meditation practice between your mind as it is and the meditation instructions you use. In Unlearning Meditation: What to Do When the Instructions Get in the Way (Shambhala Publications, 2010, $16.95 paper, 224 pp.), Siff encourages us to take a bird’s-eye view of our meditation instructions so that we can see the concepts and beliefs that are embedded within them. When we get behind the instructions and understand how the concepts within them function, we find that we often sort our meditation experiences into acceptable and unacceptable, right and wrong. This kind of rigid thinking about our practice can lead to both frustration and what Siff calls “meditator’s guilt.” For experienced meditators, “unlearning meditation” is about dropping unwanted habits from your current practice and gaining a renewed commitment to sitting. For newcomers, Siff teaches a method that he has developed called Recollective Awareness Meditation, which, as the name suggests, emphasizes recalling experiences one has had during meditation and using memory to cultivate presentmoment awareness. For all readers, Siff presents a way to practice meditation that is radical in its gentleness and openness, telling us that during meditation “anything that happens is okay.”

When reading translated work, we’re looking for the feeling of verisimilitude, especially in a book of Chinese Zen poetry like Clouds Thick, Whereabouts Unknown: Poems by Zen Monks of China (Columbia University Press, 2010, $29.50 paper, 448 pp.), where the poetic language is meant to allude to meaning that is otherwise inexpressible. So is the translator of these poems, the Chinese poetry scholar Charles Egan, credible? In a word, yes. He’s very clearly inspired by the ideas, images, and emotions found in this diverse collection of poems—a collection that ranges from the 8th to 17th centuries. How could you not be? These wandering monk-poets—Han Shan, Jiaoran, Qiji, and others—are simultaneously at home in the landscapes they traverse and full of human longing. Forget the cultural distance at which these poems were composed; they feel familiar. You experience the poets’ joys and sorrows while they search for the Way (“gibbons came to touch the clear water; birds flew down to peck the cold pears. / I should be about my task—The homeward heart has its time.”) Egan’s true gift to us in Clouds Thick, Whereabouts Unknown, however, is his scholarship. He grounds these rootless wanderers firmly in the Chinese Chan tradition. His introduction, which details the general historical and religious background of the poetry, and his endnotes, about the specific poets and poems, help to unpack the wonders in the middle. Even with Egan’s guidance, however, the meaning of many of these poems will remain elusive—but that’s kind of the point. The anthology includes paintings by Charles Chu.

With The Stories of the Lotus Sutra (Wisdom Publications, 2010, $18.95 paper, 352 pp.) Gene Reeves has written a fine companion to his accessible English translation of the Lotus Sutra. Why does this sutra, also called the Dharma Flower Sutra, call for such a commentary? Reeves—who has spent the last 25 years researching, lecturing, and writing about this particular text—tells us, “These stories are the primary skillful means through which the Dharma Flower Sutra invites us into its world, which is indeed our own world, albeit seen and experienced differently.” It’s an important point that the often unbelievable, magical world of the sutra is the same world that we readers live in. Reeves reminds us repeatedly that the purpose of these stories and parables is not to give us interesting ideas, introduce us to doctrines, or entertain us (although they will invariably do all of these things), but rather to change our lives. When the sutra stories describe impossible events—flowers raining from the heavens, fantastic castle-cities being conjured out of thin air—we should remember that they’re said to have happened in an actual, physical place in India. A story, then, is not just a finger pointing at the moon—or at least, in this case, stories are used to open up a world where the finger is not less important than the moon. Magic is real, and stories have the power to enlighten. Forget the played-out notion that fiction and Buddhism are at odds, and enter the landscape of The Stories of the Lotus Sutra—what Reeves calls “a world of enchantment.”