I am a secular Buddhist. It has taken me years to fully “come out,” and I still feel a nagging tug of insecurity, a faint aura of betrayal in declaring myself in these terms. My practice as a secular Buddhist is concerned with responding as sincerely and urgently as possible to the suffering of life in our saeculum—this world, this age in which we find ourselves now and future generations will find themselves later. I see the aim of Buddhist practice to be not the attainment of a final nirvana but rather the moment-to-moment flourishing of human life within the ethical framework of the Eightfold Path here on earth. Given what is known about the biological evolution of human beings, the emergence of self-awareness and language, the sublime complexity of the brain, and the embeddedness of such creatures in the fragile biosphere that envelops this planet, I cannot understand how after physical death there can be continuity of any personal consciousness or self, propelled by the unrelenting force of acts (karma) committed in this or previous lives. For many—perhaps most—of my coreligionists, this admission might lead them to ask: “Why, then, if you don’t believe such things, do you still call yourself a ‘Buddhist’?”

I was neither born a Buddhist nor raised in a Buddhist culture. I grew up in a broadly humanist environment, did not attend church, and was exempted from scripture classes, as they were then called, at grammar school in Watford. At the age of 18 I left England and traveled to India, where I settled in the Tibetan community around the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala. I became a Buddhist monk at the age of 21 and for ten years underwent a formal monastic education in Buddhist doctrine, philosophy, and meditation. Even in the wake of the 1960s this was considered a highly unconventional career path. Buddhism, when it was mentioned at all in those days, was dismissed by mainstream Western media as a marginal though benign spiritual preoccupation of ex- (or not so ex-) hippies and the occasional avant-garde psychiatrist. I would have dismissed as a fantasist anyone who told me that in 40 years meditation would be available in the U.K. on the National Health Service, and a U.S. congressman (Tim Ryan) would publish a book called A Mindful Nation: How a Simple Practice Can Help Us Reduce Stress, Improve Performance, and Recapture the American Spirit.

Buddhism had its origins in 5th-century B.C.E. India and eventually spread throughout the whole of Asia, but it was not until the middle of the 19th century that Westerners had any inkling at all of what it taught and stood for. The abrupt discovery that Gotama Buddha was a historical figure every bit as real as Jesus Christ, and whose influence had spread just as far and wide, came as a shock to the imperial conceits of Victorian England. While a tiny handful of Europeans converted to Buddhism from the late 19th century onward, it was only in the late 1960s that the dharma started to go viral in the West. In contrast to Christianity, which slowly and painfully struggled to come to terms with the consequences of the Renaissance, the European enlightenment, natural science, democracy, and secularization, Buddhism was catapulted into modernity from deeply conservative, agrarian societies in Asia, which were either geographically remote or cut off from the rest of the world through political isolation. After a lifetime of work in Buddhist studies, the scholar and translator Edward Conze drew the conclusion that “Buddhism hasn’t had an original idea in a thousand years.” When Buddhist communities collided with modernity in the course of the 20th century, they were unprepared for the new kinds of questions and challenges their religion would face in a rapidly changing global and secular world.

I suspect that a considerable part of the Western enthusiasm for things Buddhist may still be a Romantic projection of our yearnings for truth and holiness onto those distant places and peoples about which we know the least. I am sometimes alarmed at the uncritical willingness of Westerners to accept at face value whatever is uttered by a Tibetan lama or Burmese sayadaw, while they would be generally skeptical were something comparable said by a Christian bishop or Cambridge don. I do believe that Buddhist philosophy, ethics, and meditation have something to offer in helping us come to terms with many of the personal and social dilemmas of our world. But there are real challenges in translating Buddhist practices, values, and ideas into comprehensive forms of life that are more than just a set of skills acquired in courses on mindfulness-based stress-reduction and that can flourish just as well outside meditation retreat centers as within them. Buddhism might require some radical surgery if it is to get to grips with modernity and find a voice that can speak to the conditions of this saeculum.

So what sort of Buddhism does a self-declared secular Buddhist like myself advocate? For me, secular Buddhism is not just another modernist reconfiguration of a traditional form of Asian Buddhism. It is neither a reformed Theravada Buddhism (like the Vipassana movement), a reformed Tibetan tradition (like Shambhala Buddhism), a reformed Nichiren school (like the Soka Gakkai), a reformed Zen lineage (like the Order of Interbeing) nor a reformed hybrid of some or all of the above (like the Triratna Order, formerly the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order). It is more radical than any of these: it seeks to return to the roots of the Buddhist tradition and rethink Buddhism from the ground up.

In exploring such roots, secular Buddhists find themselves excavating two fields that have been opened up in the past century by modern translators and scholars. The first of these fields consists of the earliest discourses attributed to Siddhattha Gotama, which are primarily found in the Pali canon of the Theravada school. We are exceptionally fortunate as English speakers to have not only a complete translation of the Pali canon but one that is continually being improved—something that speakers of other European languages can still only dream of. The second of these fields is that of our increasingly detailed (though still disputed and incomplete) understanding of the historical, social, political, religious, and philosophical conditions that prevailed during the Buddha’s lifetime in 5th-century B.C.E. India. Thanks to scholars like Richard Gombrich [interviewed in this issue], we are beginning to see more clearly the kind of world in which the Buddha taught. Together, these two fields provide a fertile soil for the project of rethinking—perhaps reimagining—the dharma from the ground up.

Yet this very wealth of material also raises serious difficulties in interpretation. The Pali canon is a complex tapestry of linguistic and rhetorical styles, shot through with conflicting ideas, doctrines, and images, all assembled and elaborated over about four centuries. The canon does not speak with a single voice. How then to distinguish between what is likely to have been the word of the Buddha as opposed to a well-intended “clarification” added by a later commentator? We are not yet—and may never be—at a point where such questions can be answered with certainty. Be that as it may, as a Buddhist practitioner I look to the Buddha’s discourses not just for scholarly knowledge but in order to help me come to terms with what the Chinese call the “great matter of birth and death.” It is in this sense that my secular Buddhism still has a religious quality to it, because it is the conscious expression of my “ultimate concern”—as the theologian Paul Tillich once defined “faith.” As one who feels an urgency about such concerns, I am bound, therefore, to risk choices of interpretation now that may or may not turn out to be viable later.

My starting point is to bracket anything attributed to the Buddha in the canon that could just as well have been said by a brahmin priest or Jain monk of the same period. So when the Buddha says that a certain action will produce a good or bad result in a future heaven or hell, or when he speaks of bringing to an end the repetitive cycle of rebirth and death in order to attain nirvana, I take such utterances to be determined by the common metaphysical outlook of that time rather than reflecting an intrinsic component of the dharma. I thus give central importance to those teachings in the Buddha’s dharma that cannot be derived from the Indian worldview of the 5th century B.C.E.

I would suggest tentatively that this “bracketing” of metaphysical views leaves us with four distinctive key ideas that do not appear to have direct precedents in Indian tradition. I call them the four P’s:

1. The principle of conditionality

2. The process of four noble tasks (truths)

3. The practice of mindful awareness

4. The power of self-reliance

Some time ago I realized that what I found most difficult to accept in Buddhism were those beliefs that it shared with its sister Indian religions Hinduism and Jainism. Yet when you bracket those beliefs, you are left not with a fragmentary and emasculated teaching but with an entirely adequate ethical, philosophical, and practical framework for living your life in this world. Thus what is truly original in the Buddha’s teaching, I discovered, was his secular outlook.

And when you bracket the quasi-divine attributes that the figure of the Buddha is believed to possess—a fleshy head-protuberance, golden skin, and so forth—and focus on the episodes in the canon that recount his often fraught dealings with his contemporaries, then the humanity of Siddhattha Gotama begins to emerge with more clarity. All this supports what the British scholar Trevor Ling surmised nearly 50 years ago: that what we now know as “Buddhism” started life as an embryonic civilization or culture that then mutated into another organized Indian religion. Secular Buddhism, which seeks to articulate a way of practicing the dharma in this world and time, thus finds vindication through its critical return to canonical sources, and its attempts to recover a vision of Gotamas’s own saeculum.

And when you bracket the quasi-divine attributes that the figure of the Buddha is believed to possess—a fleshy head-protuberance, golden skin, and so forth—and focus on the episodes in the canon that recount his often fraught dealings with his contemporaries, then the humanity of Siddhattha Gotama begins to emerge with more clarity. All this supports what the British scholar Trevor Ling surmised nearly 50 years ago: that what we now know as “Buddhism” started life as an embryonic civilization or culture that then mutated into another organized Indian religion. Secular Buddhism, which seeks to articulate a way of practicing the dharma in this world and time, thus finds vindication through its critical return to canonical sources, and its attempts to recover a vision of Gotamas’s own saeculum.

Above all, secular Buddhism is something to do, not something to believe in. This pragmatism is evident in many of the classical parables: the poisoned arrow, the city, the raft—as well as in the Buddha’s presentation of his four “noble truths” as a range of tasks to be performed rather than a set of propositions to be affirmed. Instead of trying to justify the belief that “life is suffering” (the first noble truth), one seeks to embrace and deal wisely with suffering when it occurs. Instead of trying to convince oneself that “craving is the origin of suffering” (the second noble truth), one seeks to let go of and not get tangled up in craving whenever it rises up in one’s body or mind. From this perspective it is irrelevant whether the statements “life is suffering” or “craving is the origin of suffering” are true or false. Why? Because these four so-called “truths” are not propositions that one accepts as a believer or rejects as a nonbeliever. They are suggestions to do something that might make a difference in the world in which you coexist with others now.

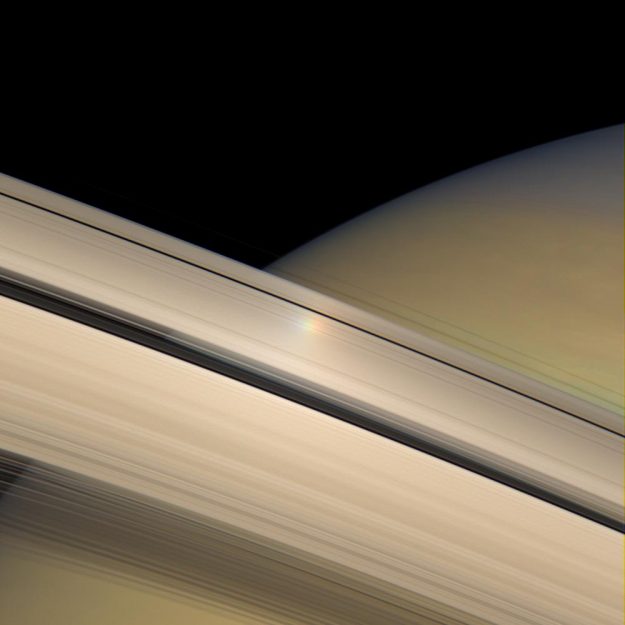

Awakening, therefore, is not a mystical insight into the true nature of mind or reality (which always, weirdly enough, accords with the established views of one’s brand of Buddhism) but rather the opening up of a way of being in this world that is no longer determined by one’s greed, hatred, fear, and selfishness. Thus awakening is not a state but a process: an ethical way of life and commitment that enables human flourishing. As such, it is no longer the exclusive preserve of enlightened teachers or accomplished yogis. Likewise, nirvana—the stopping of craving—is not the goal of the path but its very source. For human flourishing first stirs in that clear, bright, empty space where neurotic self-centredness realizes that it has no ground at all to stand on. One is then freed to pour forth like sunlight.

Such a view of the dharma fits well with the English theologian Don Cupitt’s vision of a “solar ethics.” In Room 33 of the British Museum you will find a small clay Gandharan bas-relief from the 2nd century C.E. that represents the Buddha as a stylized image of the sun placed on a seat beneath the Bodhi tree. In the Pali canon, Gotama describes himself as belonging to the “solar lineage” (adiccagotta), while others call him by the epithet “solar friend” (adiccamitta). A true friend (kalyanamitta), he remarks, is one who casts light on the path ahead just as the rising sun illuminates the earth. Yet as Buddhism grew into an organized Indian religion, it seemed to lose sight of its solar origins and turned lunar. Nirvana is often compared to the moon: cool, impassive, remote, and also—as they didn’t know then but we know now—a pale reflection of an extraordinary source of heat and light. Perhaps we have reached a time when we need to recover and practice again a solar dharma, one concerned with shedding its light (wisdom) and heat (compassion) onto and into this world, which, as far as we know, might be the only one that ever has been or ever will be.