A few years ago, I attended a teaching in a monastery near the great Boudhnath shrine in Kathmandu, Nepal. Chökyi Nyima Rinpoche, a Tibetan lama famous for his lively and accessible talks, was debating an ever-vexing question.

“So,” the Rinpoche began. “What is Buddhism? Is it a religion? Or science?—What I think and also true!—is that most religions are on one side; while the sciences— physics, chemistry, biology—are on another side. Buddha-dharma is in the middle. On the one hand, Buddha-dharma is a religion; but Buddhism is not really a religion! On the other hand, Buddha-dharma is a science; but it is not really a science!

“So what is Buddhism? Hmmm?” The Rinpoche scanned the room. “Buddhism is common sense: truth.”

As he concluded, a flash went off: one of the students had taken a snapshot. And I remember thinking, at that moment, that Buddhism could also be described in a less esoteric way: as a lens. The dharma represents, above all else, an objective point of view. It is a tool for viewing reality as it is, without the filters of hope or fear, aversion or attachment.

Of all the visual arts, then, photography may have the best shot at embodying Buddhist principles. The photographer’s lens, used skillfully, captures tiny parcels of truth; portraits of the present moment.

“Photography in general has a resonant quality when it comes to Buddhist issues,” agrees Michael Light, a California photographer whose work scans vast landscapes and cosmic energies with a dispassionate eye. “You are artificially freezing a moment out of a flow, out of a continuum. And that game, that dance between the river and what you choose to take out of the river, is about impermanence.”

Some might call this attachment; Light shakes his head.

“Why do we love great paintings, or music?” Light sits in the kitchen of his rustic Bay Area home, which clings to a long pier near the Richmond—San Rafael Bridge. An intense man, now forty-two, with radiant blue eyes and a passion for science, he devoted many of his earlier years to environmental work. “A symphony, or any art, is a kind of clinging. But it’s mainly a record of a process, a record of losing oneself. I would hope that my work, too, involves losing myself, abandoning myself to larger forces while being sharp enough to perceive the larger forces in the first place.”

Paradoxically, the images that have brought Light global acclaim did not enter the art world through his lens. He established his reputation through a kind of curatorship: by compiling two books of archival photographs, both of which presented familiar images in revolutionary ways.

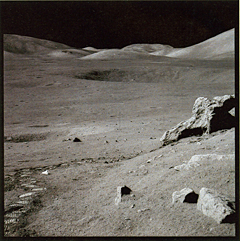

The first, Full Moon, is a collection of 129 images taken by the Apollo astronauts during the lunar missions of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Digitally reprocessed from NASA masters, these photographs portray the airless Moon (and the journey there) with a razor-sharpness absent in the pictures we’ve all seen in magazines. A more recent book, 100 Suns, presents archival images of mushroom clouds, taken between July 1945 and November 1962. This was the era of “visible nuclear testing”—the detonation of nuclear weapons in the atmosphere—by the United States.

My own introduction to Light’s work occurred at an exhibition of the Full Moon images at San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art. Space exploration has long been one of my passions, and I’d followed the Apollo missions as a young teenager. But nothing I’d seen on TV or in the pages of Life had prepared me for these mural-sized landscapes of the lunar surface. Standing before them, I could imagine I was actually on the Moon.

“What is landscape?” Light leans forward, keen to reach the core of the subject. “It’s simply reflective surface—rock, water, mineral matter—illuminated by radiation, or visible light. Without an atmosphere, there is no scattering of that light. So the lunar images depict an amazing place—but they also depict a light of uncanny clarity.”

I recognize the effect from my trips to Tibet. In the thin air of the high plateau, every object—from nearby pebbles to the peaks of distant mountains—seems vivid and distinct. I’m curious to know why that quality doesn’t come through in NASA’s photos of the moonwalks, which never gave me the sense of actually being there.

“NASA made the decision, in 1958, to disseminate their imagery across the world,” Light explains. “They did this by continually recopying their masters. Each time, the copies got softer and blurrier. So NASA’s method of making these images available to the public ruined one of the most amazing things about them, which is the clarity of light.”

Light negotiated for a year and a half to get access to NASA’s master images, which he scanned at film-grain resolution and printed using a state-of-the-art digital process. The resulting images are super-sharp, almost exactly what the astronauts captured on film.

Aside from their technical appeal, there’s a Zen component to the scenes. They seem the ultimate expression ofkaresansui: the “dry landscape” of Japanese rock gardens. Looking deep into one of the photographs, I experience a dizzying sense of spaciousness. The ground is absolutely still; the black lunar sky is empty and infinite. There is literally nothing there; nothing but ground, light, and space. Nothing to cling to; no obstructions. The scenes are both disorienting and inspiring: an unmitigated view of emptiness. The Moon would be a great place for a retreat.

“I’ve always felt a real affinity to the fundamentals of Zen practice,” Light allows. “The minimalism of Zen art, the spareness of it, has always been of immense appeal. In fact, there’s an image in Full Moon—one of my favorite pictures in the entire book—that I call the “Zen Garden.’” [See photo this page.]

The photo, from the Apollo 17 mission in 1971, was taken in the Valley of Taurus Litrow. There are no humans in the image. In the foreground is a large boulder, which the astronauts named “Split Rock.” Barely visible in the distance is the lunar lander, a buglike speck two miles away. And there on the lunar surface, surrounded by bootprints, is a scrap of litter: a discarded plastic sample bag.

“I’ve always loved this image, because it’s a very spare arrangement of rocks, and there are these footprints, and a piece of trash,” Light grins. “It’s not the Zen garden of classical Japan—but it is the Zen garden of contemporary America. And it is the Zen garden of all serious, engaged landscape photography.”

After the mid-1970s, Light explains, there was a shift away from the styles of Ansel Adams or Edward Weston—either of whom would have composed the picture without the trash or footprints—in favor of a less illusory view.

“Around that time a whole crop of artists said, ‘No; this is our environment. It’s got trash in it, and it’s got footprints. The responsible way to represent the landscape is with the beauty, and the trash, and the footprints: everything interacting. We don’t need to go to Yosemite to talk about landscape; we can go to industrial L.A. And maybe, depending on the artist, we can find the sublime there as well.’”

His comment reminds me of the sequence in the film American Beauty, where a plastic bag, caught in a wind vortex, dances amid rose petals. Many people viewed the scene as a representation of Zen perfection; a vision of the sublime within the mundane. Finding that relationship seems to be Light’s strongest suit. One warm summer night, I joined him for a helicopter flight over Los Angeles. The endless expanse of the sodium-lit metropolis was not my idea of a Buddha-field, but Light’s lens captured the display without panic or ceremony.

“Los Angeles used to seem the maw of the apocalypse,” Light concedes, leafing through a portfolio of his Los Angeles work. “A symbol of everything that’s wrong with the world. Yes, L.A. has got its problems, but it no longer makes me despair. I just don’t have delusions of purity anymore. When I was young, working with the Sierra Club, I thought there was a clear line between nature and culture. I no longer believe that. We are now so numerous, and so capable, that the Earth is a human park. It’s all culture at this point. That’s not necessarily bad. We can be a terrible caretaker, or we can tend our garden well—but it is a garden, and not a wilderness anymore.”

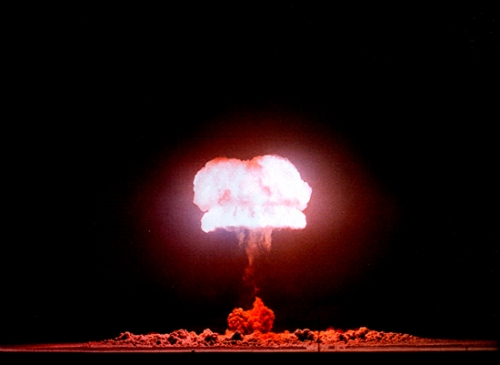

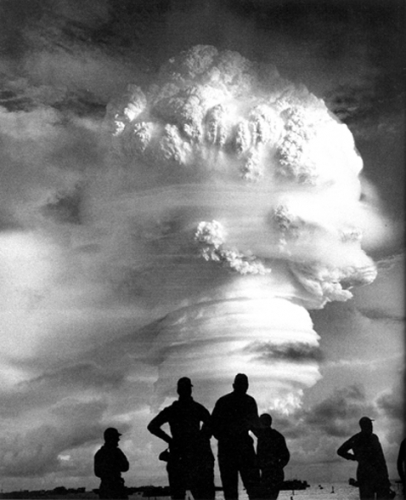

This conviction comes across with brutal force in 100 Suns, Light’s watershed collection of images from the Los Alamos National Laboratory and the U.S. National Archives. Some of the radiant fireballs captured in these photographs—a record of the most wrathful forces ever unleashed—are indeed temporary suns, as awesome and lethal as Shiva’s third eye. Others, billowing in abstract towers, remind me of the mist-shrouded mountains depicted by Chinese landscape painters.

Like the lunar images in Full Moon, the settings portrayed in 100 Suns are beautiful but forbidding; places where an unprotected human form could never survive. And it’s not just our physical form that faces annihilation here. Our projections into the future—as individuals, and as a species—are also atomized by these blasts, with their implicit threat of extinction.

Light sees this adventure, this journey “to the point where the ego falls apart,” as part of his artistic process. I liken it tochöd, the Tibetan charnel-ground meditation practice. Just leafing through 100 Suns is like taking a sightseeing tour of the bardo: the calamitous terrain between death and rebirth. I ask Light how he reconciles the horror of these photographs with their undeniable beauty.

“I think there is something spectacularly beautiful about power, and scale, and those moments and places where we are reminded of our actual size in the face of the immensity around us,” confirms Light. “In this case it’s particularly complicated, because the images remind us not only of our utter inconsequence, but also of our brilliance. All of a sudden we are tremendously consequential, because we can fabricate our own stars.”

“Did you find any hope in that prospect?”

“I wouldn’t say it was hopeful for me. The main impact,” Light allows, “was one of acceptance. It was simply, ‘This is what we do.’ But coming to that realization, that demystification, was itself a point of hope. This is just knowledge: like building a bridge, or decoding the genome. There’s no way to control it. It will be there, with us, until the last breath of the human race.”

There’s a kind of egolessness inherent in working with archival images. Light often walks the line between joyful immersion in a public icon—like the moon landings— and vague annoyance that his own contribution, for many viewers, seems minimal.

“It’s a constant insecurity for me. Because many people just look at the subject, and never realize that somebody named Mike Light came along, and had the idea to put together this kind of exhibition.”

Light’s second passion, after photography, is piloting. His current work combines the best of both worlds. During the past two years he has been shooting, from the air, the arid West. His flights arc over the scrubby deserts of California and Nevada, embracing both the majesty of the landscape and the relentless encroachment of humanity around “urban agglomerations” like Las Vegas, Phoenix, and Los Angeles.

“The images are basically studies of light, space, and geology—beautiful images of a certain kind of emptiness. On a primal level, I’m interested in seeing how that space is filling up: with us.”

Given the breadth of Light’s interests, it’s difficult to link them with a common thread. Even the artist hesitates, tongue-tied, at the prospect. But his answer, when it comes, seems to fit.

“An overall description of my work would have to include seduction and beauty, and the sheer pleasure of observation. Tempered by a sometimes sad, but hopefully clear-eyed, evaluation of what humans do to their environment, their surroundings, and, by extension, to each other.

“But it also comes back, perceptually, to what I consider a Buddhist approach. The light of the universe is out there, 24/7, in all its horror and magnificence. To pay attention, to remain focused, to be awake—those are the challenges.”

Contributing editor Jeff Greenwald’s last piece for Tricycle, “Gross Anatomy,” appeared in the Fall 2005 issue.