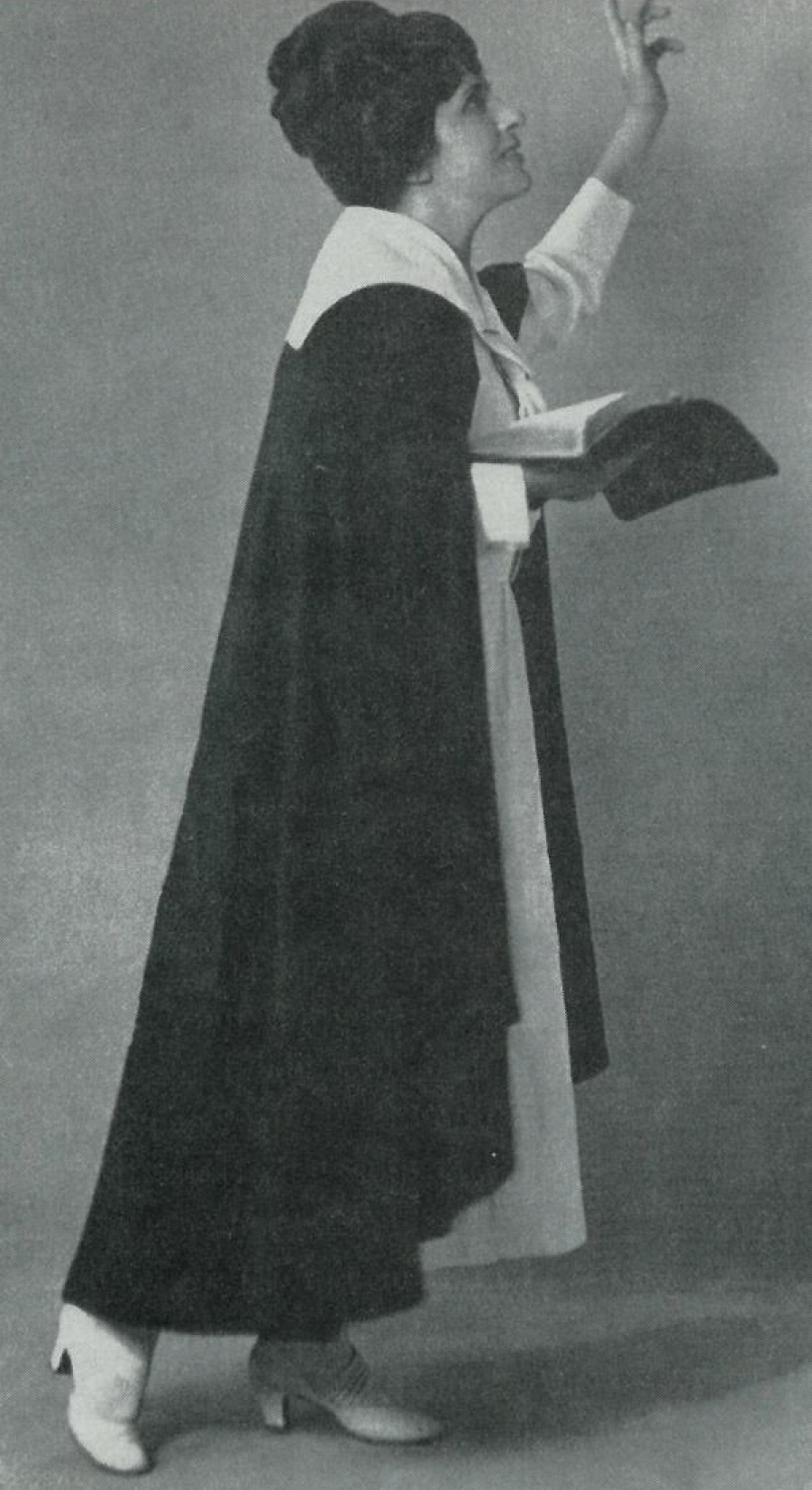

Julius Goldwater wasn’t the only boy in Los Angeles in the Roaring Twenties who swooned over Aimée Semple McPherson. A Canadian farm girl turned superstar evangelist, “Sister Aimée” was the Madonna of her day, a sexy celebrity with first-name-only status who knew how to make religion fun. Her revivals were short on fire and brimstone and long on heavenly bliss; her shtick was part preaching, part healing, and part vamping. Charlie Chaplin called her a great actress. Goldwater recalls that “she put on a good show.” One day, as ushers fanned out across the 5,000 seats of the $1.5-million headquarters of her International Church of the Foursquare Gospel, Sister Aimée told her admirers to jiggle the coins in their pockets. “Don’t bother with that,” she added with a grin, “bring up the paper!”

Goldwater was only fifteen when McPherson first sashayed down the aisle of her glitzy new Angelus Temple in praise of mammon. And he was still a teenager when she and her lover scandalized the nation by skipping off to Mexico to violate the Seventh Commandment. For Goldwater, this tryst was a lesson in the dangers of mixing show time and church time, the Almighty God and the almighty dollar. It was a lesson he would not forget.

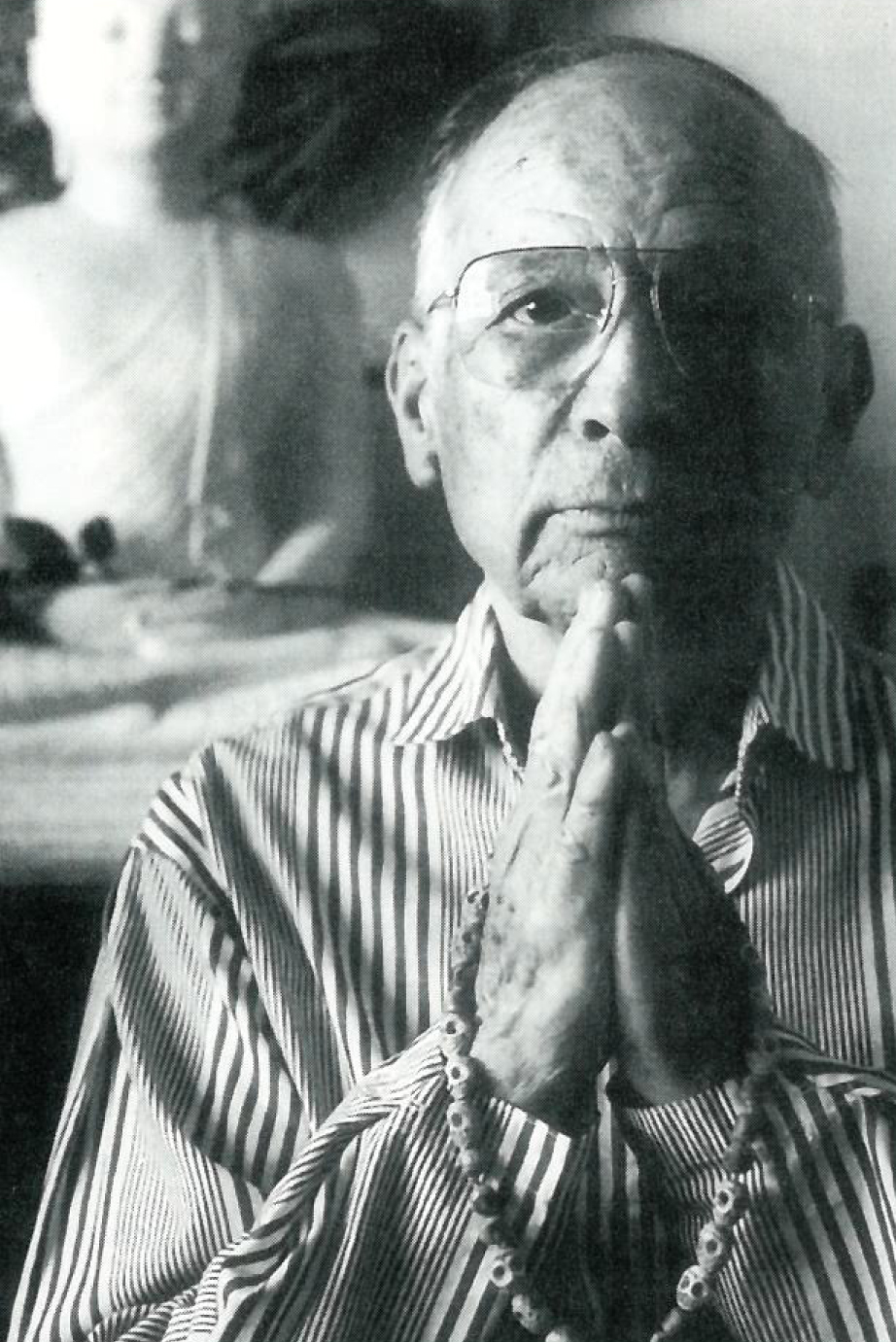

Reverend Julius Goldwater, who celebrated his eighty-ninth birthday this year, may be the oldest living European-American convert to Buddhism. He discovered Buddhism thirty years before the Beat Generation began reading Dwight Goddard’s Buddhist Bible, and seven decades before the advent of what The New Yorker recently called the current Buddhist “frenzy.”

He was born German-American and Jewish in Los Angeles in 1908. His mother planned to raise him as an observant Jew, but she died when he was two-and-a-half. His father later put him through two years of Jewish Sunday School. “It didn’t take,” Goldwater reports, but his early encounters with Judaism instilled in him a spiritual thirst that would later lead him to McPherson’s revivals as well as Inayat Khan’s Sufi lectures, Manly P. Hall’s occult speculations, Krishnamurti’s cryptic reflections on the pathless path, and Swami Prabhavananda’s Vedantist Hinduism. Of all his early teachers, Goldwater was the closest to Hall. A homespun philosopher and prolific writer who divined a common core at the heart of all religions, Hall became Goldwater’s mentor, inviting him to services at his Church of the People and allowing him access to one of the world’s largest libraries on parapsychology, mysticism, and Eastern religions.

Goldwater didn’t give Buddhism much thought, however, until he and his father moved to Hawaii in the late twenties. The Hompa Hongwanji of Japan had sent Jodo Shinshu (True Pure Land) Buddhist missionaries to Hawaii in 1889, so Shin Buddhism, at the time of Goldwater’s arrival, was the dominant form of Buddhism within the islands’ Japanese-American population. However, because the Issei (first-generation Japanese Americans) conducted services in Japanese, there were few Caucasian sympathizers, and English-speaking Nisei (U.S.-born, second-generation) were beginning to defect to Christian churches. In an effort to reach out to Caucasians and the Nisei, in the early 1920s, Honolulu’s Hompa Hongwanji temple began to offer services in English. Goldwater went with a friend to one of those services. There he met Rev. Ernest Hunt. Hawaii’s only European-American Buddhist minister and a committed Buddhist ecumenist. Hunt excelled at explaining his “international Buddhism” to the U.S.-born Nisei. When Hunt spoke, Goldwater says, “something grabbed me.” It was the claim that Buddhist teachings were “self-validating as you go along.” If you do what the dharma tells you to do, Hunt promised, you will see the results.

Goldwater begged Hunt to accept him as a Buddhist, but Hunt only warned him not to “monkey around.” Goldwater didn’t. In Honolulu in 1928, during a ceremony at the “Temple of Amidha’s Fulfilled Vow,” he took formal vows and became one of America’s first Jewish Buddhists.

At the urging of his wife, Pearl Wicker, a Lutheran whom he married in a Jodo Shinshu ceremony in Hawaii, Goldwater returned to Los Angeles in the midst of the Depression. Now known as Subhadra (after one of the last disciples to see Shakyamuni before he died), Goldwater joined Little Tokyo’s Nishi Hongwanji, a Jodo Shinshu temple affiliated with the Buddhist Mission of North America. As the only Caucasian member of the temple, he was especially beloved by Nisei boys and girls, whom he instantly won over by organizing a youth dance.

Goldwater’s work at the Nishi Hongwanji caught the eye of leading Jodo Shinshu priests, who urged him to travel to Japan for ordination. Nisei youth were jumping too eagerly into the American melting pot. If Goldwater added the traditional authority of Buddhist ordination to the charismatic cachet of his American roots, perhaps he could stem the tide. “I couldn’t have been less interested” in the priesthood, Goldwater confesses, “but their need was so great.” He was ordained in Kyoto in the Jodo Shinshu tradition in 1936.

He then went to China, where he demonstrated his commitment to Buddhist ecumenism by receiving ordination once again, this time in Hangchow. “I knew I wasn’t worthy,” Goldwater says, “but I was inwardly kind of proud. At last I was an accepted Buddhist.”

There is a saying among Japanese-American Buddhists that “the priests in Japan live an unchanging life of rice paddies, while ministers in America live a life of sheep.” Rev. Goldwater’s new life as the first European-American Jodo Shinshu minister on the mainland was a shepherd’s life. He led English-language services, taught Sunday School, and organized youth groups – anything to keep his sheep at the Nishi Hongwanji in the fold. He also traveled up and down the West Coast, “preaching the gospel” to Japanese-Americans in agricultural settlements as far north as Seattle, Washington.

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. In February 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, clearing the way for the removal of more than 100,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast into what Roosevelt himself admitted were “concentration camps.”

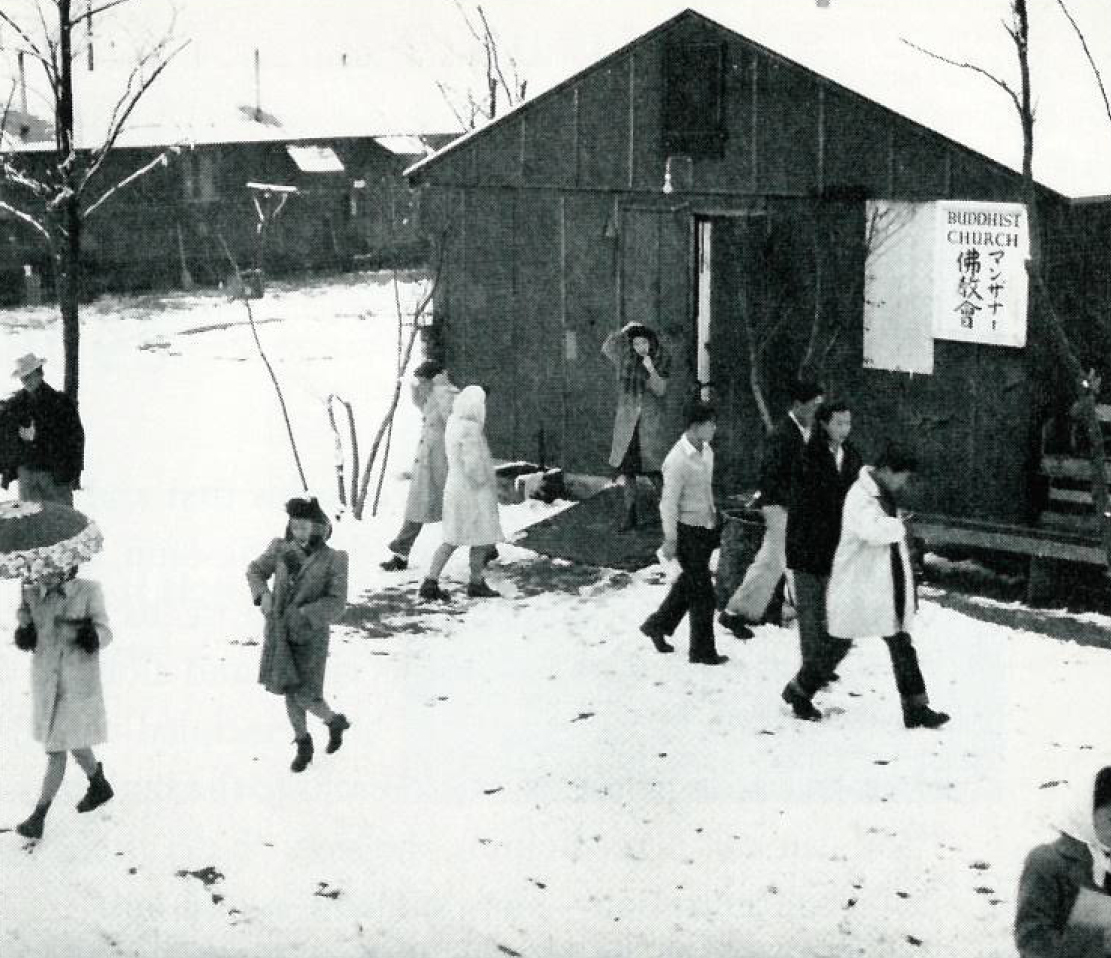

Before World War II, Goldwater had been a groundbreaking but relatively insignificant American Buddhist – a minor presence even at his home temple (which typically had ten Japanese-speaking priests in residence). But Executive Order 9066 whittled membership in the temple to one. As Goldwater watched in horror, his fellow Buddhists were relocated, first to temporary internment camps at places like the Santa Anita racetrack and later to more permanent concentration camps in locations as far away as Rohmer, Arkansas. What had been a thriving temple was reduced to a storehouse for the family treasures of evacuees. And Goldwater became a shepherd of Buddhist exiles scattered across the world’s newest diaspora.

For the next four years, Goldwater ministered to his sheep like the Methodist circuit riders of the nineteenth century. His horse was a “snappy” Chrysler, and he hitched it to outposts as far-flung as Gila River, Arizona, and Heart Mountain, Wyoming. At a time when the rest of America viewed “Japs” as strangers from another planet, Goldwater treated each evacuee with attentive compassion. There were ten concentration camps, and he visited them all, some many times over. At Santa Anita, he saw human beings housed in stables ankle-deep in horse dung, and at camps across the country, he heard stories of prison guards sexually molesting young children. Because “there wasn’t anyone else to do it,” he trudged from camp to camp, distributing coffee, candy, and self-published Buddhist books.

Rev. A. Arthur Takemoto attended Goldwater’s youth dances in the 1930s. Interned at Poston, Arizona, and Topaz, Utah, he remembers the difficulties and dangers of practicing Buddhism in the camps. Many Buddhists stayed in the closet for fear of being labeled anti-American. Those who were out had to build new sanghas from scratch. Evacuees couldn’t take much with them. Some priests smuggled in Buddha statues, and one enterprising Buddhist crafted a shrine out of discarded apple crates. “Everything was improvised,” Takemoto says, and Goldwater was among the improvisers.

During the war, Goldwater founded the Buddhist Brotherhood of America, an ecumenical organization devoted to printing and distributing nonsectarian Buddhist books to internees. Among these books was an English-language worship manual that incorporated into Buddhist practice Christian elements such as catechisms, creeds, and hymns (some sung to Protestant strains Goldwater had heard on the lips of McPherson’s 200-voice chorus). Long before Philip Kapleau, Jiyu Kennett, and other Zen teachers agitated for adapting Buddhism to American soil, Goldwater was using “skillful means” to Americanize Buddhism.

He did this not only to make it easier for the Nisei to practice Buddhism but also to validate Buddhism in American eyes. “Everybody thought the Japanese were from Mars,” Goldwater explains. The FBI equated Buddhism with Shinto and Shinto with fanatical allegiance to the emperor. Goldwater and like-minded Nisei Buddhists, many of whom, like Takemoto, were tracked by the FBI, tried to correct that misunderstanding by emphasizing the “Americanness” of Buddhism.

Goldwater was not able to convince his fellow Americans that Buddhism should stand side-by-side with Protestantism, Catholicism, and Judaism as a legitimate national faith. But he did convince many fellow Buddhists that to survive in America they would have to assimilate. In 1944, at Goldwater’s urging, the Buddhist Mission of North America changed its name to the Buddhist Churches of America. After the war, a new generation of Goldwater-influenced Nisei priests carried on the work of accommodation, transforming the B.C.A. into the country’s largest Buddhist body.

Not everyone was happy with this turn of events. As a member of the Japan-born Issei generation, Goldwater’s bishop was no fan of Americanization. He hated youth dances and battled Goldwater over using the temple as a storage facility for evacuees. After the war, he sued Goldwater for temple mismanagement. It wasn’t fair, Takemoto says, but the bishop prevailed on a technicality. Undaunted, Goldwater continued to practice his own version of engaged Buddhism. With Takemoto’s help, he opened a number of Buddhist hostels designed to ease the transition of internees back to postwar normalcy.

In the half-century since World War II, Goldwater has lived a quiet life in Los Angeles. The brick and concrete fortress that was once his home temple now houses the Japanese American National Museum. Goldwater, still happily married to his first and only wife, does not attend the new Nishi Hongwanji, but he does convene a Buddhist study group in his home. Each morning and night, he sits silent and alone in a practice that, in keeping with his principled eclecticism, owes as much to the Quakers as to the Buddhists. “You can call it meditation,” he says, “but I prefer to call it concentration one-pointedness of mind.”

Goldwater’s Buddhism eludes simple labels. He doesn’t chant the nembutsu and doesn’t like to be called a Shin Buddhist. (“In Jodo Shinshu, Buddhism is a matter of faith,” he explains, while real Buddhism “has nothing to do with faith.”) His practice is “Indian Buddhism, with lots of Chinese and very little Japanese thrown in.” In Dharma Bums, Ray Smith (the alter ego of author Jack Kerouac and another violator of conventional Buddhist boundaries) calls himself “an old-fashioned dreamy Hinayana coward of later Mahayanism.” Take out the coward, and that’s a fair description of Goldwater, who like Khan, Hall, Hunt, Krishnamurti, and Prabhavananda, insists that the rivers of true spirituality do not respect the banks of sectarian religious divisions.

Goldwater spent time with D. T. Suzuki in Los Angeles and with Nyogen Senzaki in the camps, and remembers both Zen teachers with respect. He also admired theosophist Katherine Tingley, though he regards theosophy as “an imitation introduction to Buddhism,” a “watered-down version” of the true dharma. He thinks less of the Beats (“Buddha Bums” he calls them), whose use of drugs appalled him, and of Alan Watts, who, by his reckoning, practiced Buddhism only two weeks a month.

For Goldwater, Watts is like MacPherson—an example of the bugaboo of what the Chinese Buddhist reformer Tai-hsu decried as “churchdom.” “All churches, no matter what the religion, are primarily concerned with raising money to support themselves,” Goldwater says. Unfortunately, the marriage of religion and economics can only produce spiritual counterfeits—“genuine fakes” like Watts and McPherson.

Perhaps that’s why Goldwater finds the current Tibetan Buddhist vogue troubling. In his view, Snickers ads featuring Tibetan monks and Microsoft ads starring the Dalai Lama aren’t spreading Buddhism; they’re exploiting it. And thanks to The Little Buddha, there is now an entire American generation that equates the life of Gautama Buddha with the acting of Keanu Reeves. “Everyone in Hollywood wants to belong to the Buddhist religion now,” Goldwater says, “but none of them are real Buddhists.”

If Goldwater underestimates Sin City’s Buddhist population, it’s because he worries that the commercialization of the dharma will obscure Buddhism’s true purpose. Freedom, according to Goldwater, is the essence of Buddhism. Real Buddhists struggle to free their minds from ignorance and the world from oppression. When Goldwater says, “Buddhism is more American than America,” he means that while politicians talk about freedom, Buddhists make an active practice of it. During World War II, the U.S. government made an active practice of imprisoning Japanese Americans. Goldwater struggled to mitigate their suffering and to work for their emancipation.

The United States began to balance its karmic accounts in 1989 when President Bush signed a law allocating $20,000 in reparations to each living Japanese American internee. Mrs. Jane Imamura was among the recipients. She and her husband had used books and incense provided by Goldwater during Buddhist services in the Gila River camp, and, after the war, they had taken charge of one of Goldwater’s halfway houses. She remembers Goldwater as “a very, very compassionate person” who demonstrated during the war that Buddhism, at its best, is a religion of compassionate engagement with a world of suffering. She sent Goldwater $500 of her reparations payment with a letter of thanks. “I won’t ever cash it,” Goldwater says. He wasn’t in it for the money.