Last winter I made a pilgrimage to Bodh Gaya for an intensive phowa course with Ayang Rinpoche. This practice, he explained, “is the quickest and most direct path for ending the cycle of rebirth.” It involves learning to transfer consciousness out of the body through the crown of the head at the moment of death.

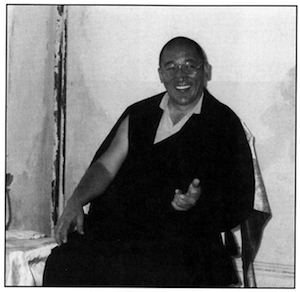

Ayang Rinpoche, a Tibetan tulku of the Drikung Kagyu lineage, teaches phowa courses throughout the West and Asia. I had taken this course with him in New York City two years ago. It was extremely detailed and complex, and I had difficulty digesting it. I was also looking for an excuse to go to India. I had not returned since 1974 when I had first taken refuge vows and spent New Year’s Eve at the stupa in Bodh Gaya.

Traveling in India proved more difficult than I had remembered. The population has doubled since 1975; the confusion, noise, and pollution seemed twice as pervasive. It took me three days and many kinds of transportation to travel from New York. I arrived on Christmas day, just as the teachings were scheduled to begin. It felt good to be back in the familiar and sacred place. The only problem was, all my information had come by word of mouth and I had no idea where the course was being held.

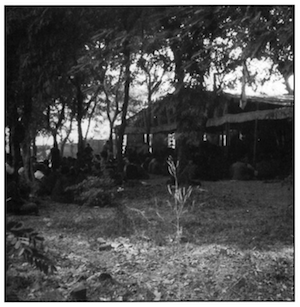

After wandering for hours, I located the teachings within the courtyards of the Mahabodhi Stupa complex, the temple that commemorates the spot where Shakyamuni Buddha attained enlightenment and which, according to legend, houses the descendant of the original Bodhi tree. On the southern side of the grounds is a lotus pond. Next to it, under a copse of trees, was a large colorful striped canopy.

Ayang Rinpoche sat on a dais at the front, with hundreds of butter lamps glowing on the adjacent altar. Dusk was falling. The air was cool, clean, and filled with birdsong. A large congregation of monks was chanting sutras over at the stupa. About 500 people sat on the burlap floor, with more spilling onto the grass outside. I counted eighty Westerners. The rest were Himalayans: Tibetans, Bhutanese, Ladakhis. Of these, about one quarter were monks and the rest laymen and laywomen, nomads, jeans-clad teenagers spinning prayer wheels, babies in bright red overalls, and old grannies on canes—all of us there to deal with the great matter of life and death. “We cannot escape death,” said Rinpoche. “When death comes, everything we have accumulated during our lifetime—loved ones, property, money, position, fame—must be left behind.”

We sat close together for two weeks, fourteen hours a day, with only short breaks for food and toilet (actually, an open field). It was cold. Most everyone, Himalayan and Westerner alike, got sick, and cough lozenges and Ayurvedic stomach remedies were passed along the rows of participants.

In the old days in Tibet, the Drikung Kagyu Phowa course was taught once every twelve years. “If you have the great blessing to receive the Drikung Phowa, you will never again be reborn in the three lower realms of samsara: the animal realm, hungry ghost realm, or hell realm.” Every Tibetan tried to attend these teachings once in his or her lifetime, and would travel for months by yak over hard terrain to get there. Ayang Rinpoche chided the Westerners for the ease of modern travel: hop on a plane, take a few trains and “bang,” we were there. It had seemed like an ordeal to get there, but later, after Rinpoche had thanked us for our sincere perseverance, I realized that physical discomfort is still used to underline the importance of receiving the teachings and that, in our own way, we were continuing a meaningful tradition.

Tibetans believe that the circumstances at the moment of death can determine one’s next existence. The teachings continually returned to how to die, and to specific practices that purify negative karma and open the crown exit door at the top of the head. These include breathing techniques, visualizations, meditations, mantras, and prayers designed to ensure that one will be able to control the pathway of consciousness out of the body into a higher realm at the moment of death. These practices are taught in a set sequence that one is then supposed to perform regularly during this lifetime. This is phowa practice.

It was also explained that as the physical body breaks down-what the Tibetans refer to as the gross outer form—the manifestation of subtle consciousness becomes more palpable. For this reason, the actual process of physical death increases the fertile possibilities for liberation. Yet, as Rinpoche reminded us, practice now would help us realize this potential. In the Zen monastery in Kyoto where I had lived, a daily recitation proclaimed, “Don’t squander your life!”

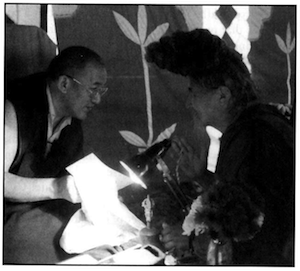

The course begins with a series of empowerments and blessings that confer permission on the initiate to receive the teachings. These transmissions are considered essential prerequisites to the successful practice of phowa, and must be received orally from a qualified teacher. In a sense, they are formal introductions to the deities that govern the processes of the practice. We received Amitabha Buddha and Vajrasattva empowerments . Amitabha guides the transference of consciousness, and Vajrasattva, the process of purification. To mark our commitment to the practice, we each vowed to complete 150,000 repetitions of the short mantra of Amitabha (six syllables) and the long mantra of Vajrasattva (one hundred syllables). As in many Tibetan practices, one visualizes the deities while chanting the mantras.

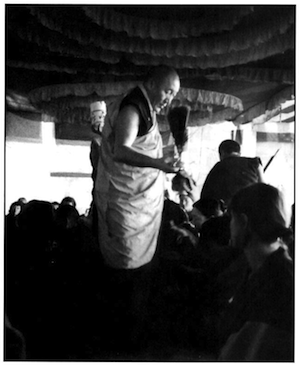

One of the striking characteristics of initiation into this practice is that people experience actual physical signs of the transmission. “Herein lies the great advantage of phowa,” Rinpoche had explained. “The signs of accomplishment come quickly, without years of strict meditation practice. Phowa is therefore especially relevant to the present day, when most of us lack the luxury of time for lengthy solitary meditation practice and are easily overwhelmed by the power of laziness and the postponement of serious practice.” These signs are most evident during “the oral transmission blessing.” Ayang Rinpoche performed this ceremony on the second day of the teachings. It took hours. Many people felt strong sensations at the top of their heads. Some started weeping. Many of us reported a buzzing vibration at the crown chakra and experienced a clear upward movement of energy along the spine.

Ayang Rinpoche explained, “At the time of death, our consciousness ordinarily leaves our body through one of the nine doors; the two eyes, two nostrils, mouth, two ears, and two lower openings. Depending upon which of these nine doors our consciousness passes through, we are reborn in one of the six realms of existence. In order to avoid being reborn in one of these six realms and continuing the endless round of birth and death, our consciousness must pass through another door located at the crown of the head where the two parietal bones meet. Traditionally, the crown is called the door of liberation. Through phowa practice, at the moment of death our consciousness can be transferred directly to the Pure Land of the Buddha Amitabha, the land beyond the samsaric suffering worlds, where one may proceed to enlightenment without obstruction.”

When asked, “Who can practice phowa?” Rinpoche responded, “The phowa meditation can be practiced by all Buddhist practitioners, whether ordained or lay followers—anyone with confidence in the Buddha, his teachings, and his followers. As a sign of successful practice of phowa, the mind of the practitioner will undergo a great positive change—it will be much more peaceful, happy, stable, and clear. Through this practice all other meditations also become much easier to accomplish. In addition, sufficiently accomplished practitioners may use phowa for the benefit of others who have reached the end of their present lives.”

Many of the westerners were longtime dharma practitioners, but many health care workers also came because of their work with the terminally ill. In open question sessions, the Westerners were generally concerned with the specifics of the death process itself—when to begin phowa and how to manage death in a hospital setting—whereas the Himalayans were more concerned with the purification of karma. The focus changed for me during these discussions. I came to see that the great value of this practice lies in its direct power to purify and dissolve karma in the here and now. Phowa became as much about the process of living as that of dying.

On one of the last days of the course, Ayang Rinpoche spoke about what to do at the actual moment of one’s own death, stressing that it was most important not to be attached to relatives, friends, or personal belongings. “Use the things you are attached to as often as you can in this lifetime, so at death you think, ‘I can’t take this with me but I’m satisfied because I used it often in this life so it is okay to let go of it.’” He told the story of a very old monk who had collected a valuable assortment of ritual objects during his lifetime which he guarded jealously. When he died, the abbot of the monastery asked one of the younger monks to clean out the man’s room. He specifically told the young monk to throw each and every object away. The monk did as he was told but was unable to throw away a particularly beautiful bowl, which he kept and hid in his own room. One day the monk entered his room to find that a large poisonous viper had crept in through the window and lay coiled in the middle of the floor. Terrified, he was unable to move. Finally the abbot came to find him. The young monk yelled that he couldn’t move because he was trapped in his room by a viper. The abbot asked him straight away if he had kept any of the old monk’s things and he admitted to secreting away the bowl. The abbot instructed him to immediately throw it out the window into the river. As soon as he did, the snake followed, never to be seen again. Rinpoche told a number of stories in which “using up” whatever you are given provided a very sensible spin on the practice of asceticism. “Live your life,” he said.

On most evenings the teachings under the tent finished by 7 P.M. followed by a quick snack and a cup of tea at the stalls outside the main gate of the temple. Some of us would buy candles and make votive offerings around the stupa, which by then was lit with thousands of candles and butter lamps. This was my favorite time of day. At 7:30 we gathered again, this time in the dark under the Bodhi tree, where Ayang Rinpoche led the chanting of the Aspiration Prayer, fifty-five pages of Tibetan text expressing one’s sincere desire to be reborn in the Pure Land of the Buddha Amitabha. Wild dogs, attracted by the singing, would come lie on the cool ground at our feet. Then Ayang Rinpoche would begin a melodic four-part chanting of the short Amitabha mantra. We would all rise together, shed our shoes, and, with Rinpoche in the lead, circumambulate the inner path surrounding the stupa and around the pathways that spiral outward, until the gates closed at 9:00 P.M.

The first night I experienced the circumambulation as a very solemn affair, momentous even. The Englishwoman next to me cried the whole evening. But then I noticed that the Tibetans were having a really wonderful time, singing away, looking into one another’s faces and smiling as they went, almost dancing, around the stupa. After a few nights the other Westerners and I loosened up, got into the spirit, picked up the pace and learned the melodies. At the end of the evening we would all stop at the entrance to the stupa to say a final prayer together, then hum the Amitabha melodies as we walked home down the dirt lanes of the quiet village, free from the fear of death.

The great Tibetan yogi Marpa the Translator said, “If you study phowa, then at the time when death is approaching you will know no despair. If beforehand you have become accustomed to the Path of Phowa, then at the time of death you will be full of cheerful confidence.”

Ayang Rinpoche said, “Death is not so far away; at any moment it can suddenly come. If we breathe out but don’t breathe in again, that is death.”

Rande Brown, president of the Amitabha Foundation of New York City, is currently translating a book about miracles in Buddhism for the Japanese sect Agon-shu.