Buddhadasa Bhikkhu (1906-1993), one of the modern Thai sangha’s most provocative interpreters of Buddhist thought, formed a wilderness tradition all his own. He was ordained as a monk in 1928, but two years later, fed up with the prevailing monastic system, he founded Wat Suan Mokkhabalarama—the Garden of Empowering Liberation Monastery—in the forest near Chaiya in southern Thailand. For Buddhadasa, the city represented the imposition of artifice on the natural. To conform with nature meant to let go of our defilements—wild nature, he taught, must be conserved in order for beings to attain nirvana. And society, by extension, must be reformed before human beings will have the wisdom to conserve and unite with nature. This approach has made Buddhadasa the inspiration for social and environmental protest worldwide, and the engaged Buddhists of today such as Thailand’s Sulak Sivaraksa have modeled their activism on his teachings.

While Buddhadasa is known as a “forest monk,” and insisted that his monks live in the forest, his view departed from that of the monks in Ajaan Mun’s tradition, and his teachings were decidedly less orthodox. The Kammatthana monks view the wilderness as an indispensably good teacher, but essentially dangerous—part of samsara and something to be transcended—whereas Buddhadasa saw nature as dharmic perfection. He promoted the integration of the scholarly and practice aspects of the Buddhist path, and during his twenties retired to the jungle for six years armed with Buddhist scriptures. Moreover, unlike the Kammatthana monks, Buddhadasa believed practitioners had to hone right understanding before any successful attempt at meditation practice could be undertaken. Ajaan Mun, by contrast, insisted on practice over study.

Whereas Kammatthana monks entered the forest in search of personal teachers, Buddhadasa sought no teacher: the transcriptions of his hundreds of dharma talks are his legacy, and while several monasteries in Thailand and around the world align themselves with his teachings, he has no formal lineage.

In an excerpt from a dharma talk on conservation, Buddhadasa lays out his notion of nature as dharma, the fundamental goodness of the wilderness, and explains how, through right view and conforming ourselves to nature, we can end suffering.

Only genuine Buddhists can conserve nature on the deepest level, the mental level. When the mental nature has been conserved, the external physical nature can conserve itself. When we talk about this inner nature, we mean a fundamental essence or element of Dhamma. When this can be preserved within, the external nature can certainly preserve itself. When this inner nature, or dhammadhatu, is conserved, there is nothing that will cause selfishness or egoism. It knows that nothing is worth clinging to as being “self,” is free of notions like “me” and “mine,” and is therefore unselfish. When there is no selfishness, there is nothing that will go out and destroy the external nature. When nothing is trying to destroy this physical nature, it is quite able to protect itself.

The Buddha referred to this inner nature as “dhammadhatu,” the dhatu (element or essence) of Dhamma (nature). Sometimes he simply called it “dhatu.” This dhatu is the source and basis for Dhamma, for all of nature. He proclaimed that “whether a Tathagata has appeared yet or not, the dhammadhatu exists absolutely and naturally.”

In other words, nothing occurs, exists, changes, or dies by itself. Nothing happens except through various causes and conditions. All change takes place through causes and conditions. These interactions of conditionality extend through the universe—mental and physical—connecting everything in a vast web of inter-dependence, inter-relationship, inter-connectedness, inter-wovenness. So supreme is this natural fact that we can call it “the law of nature” or “God.” Nothing is more powerful or awesome than this most fundamental and ever-present Truth.

Let us consider more carefully what we mean by the word “nature.” Nature (dhammajati) is all things that are born naturally, ordinarily, out of the natural order of things, that is, from Dhamma. Everything arising out of Dhamma, everything born from Dhamma, is what we mean by “nature.” This is what is absolute and has the highest power in itself. Nature has at least four fundamental aspects. If we don’t understand them, it is useless to speak of “preserving nature.” So please examine these four fundamental aspects of nature:

- nature itself;

- the law of nature;

- the duty that human beings must carry out toward nature;

- and the result that comes with performing this duty according to the law of nature.

Let’s consider ourselves. Each human being includes the body of nature, as expressed and found in our own bodies. In us there is the basic dhammic law of nature that regulates everything. Everything in these bodies consequently carries on according to the law of nature. When we have our natural duty, we practice that duty in order to maintain the correctness of nature. Depending on how we perform that duty, we experience its results or fruits: happiness, dukkha, satisfaction, dissatisfaction. Within ourselves, within just these physical bodies, we have all four meanings of nature.

In one human being, we can find all four aspects of nature. Throughout the entire world, we can find all four meanings of nature. And in the universe, including all the worlds together, we can see the body of nature, the law of nature, the duty of nature, and the result of nature.

If we understand all aspects of nature and conserve the law of nature within ourselves, it will then be impossible for selfishness and egoism to arise. When there is no ego or selfishness, there is nothing that will destroy nature, nothing that will exploit and abuse nature. Then the external, physical aspect of nature will be able to conserve itself automatically. Therefore, please be very interested in this inner nature. When there is no selfishness, we can preserve the purity and beauty of nature. Without selfishness, this world will be naturally pure and beautiful.

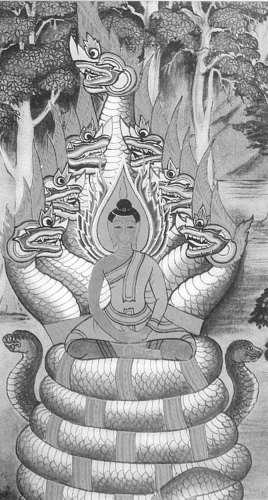

When Buddhists remember that the Buddha was born under and among trees, awakened while sitting under a tree, taught in the outdoors sitting among trees and, in the end, passed away into parinibbana beneath some trees, it is impossible not to love trees and not to want to conserve them. This too comes from maintaining a correct inner nature, and so it is natural to preserve the outer nature. In this way it isn’t very difficult to conserve the external physical nature.

In other words, Dhamma is the ecology of the mind. This is how nature has arranged things, and it has always been like this, in a most natural way. The mind with Dhamma has a natural spiritual ecology because it is fresh, beautiful, quiet, and joyful. This is most natural. It is calm and peaceful because nothing disturbs it. It contains a deep spiritual solitude, so that nothing can disturb or trouble it. Its joy is cool. The only joy that lives up to its name must be cool, not the hot happiness that is so popular in the world, but a cool joyfulness. If none of the defilements like greed, anger, fear, worry, and delusion arise, there is this perfect natural ecology of the Dhammic mind. But as soon as the defilements occur, the mind’s natural ecology is destroyed instantly. These defilements are like evil spirits or demons that destroy the mind’s natural state.

In this context, we can specify the defilement called “craving,” the craving that destroys the inner ecology of the mind and then expresses itself outward in destroying the physical ecology. This thing called “craving” must be understood well. Craving always means the foolish desire that arises out of ignorance (avijja), out of not understanding things as they actually are. Unfortunately, whenever Buddhists speak of samsara, most of them teach that every kind of desire is craving. This is incorrect. Only that which desires stupidly is properly called “craving.” If it wants intelligently, it is called sankappa (aspiration or aim), which we can call “wise want.” There is an important distinction here that should never be confused. Craving is always ignorant, no matter how we translate it into English. If, however, the desire is wise, it should be called “aspiration” or “wise aim.”

We must honor and worship the cooperative system. Take a good look. The entire cosmos is a cooperative system. The sun, the moon, the planets, and the stars are a giant cooperative. They are all inter-connected and inter-related in order to exist. Humans and animals and trees and the earth are integrated as a cooperative. The organs of our own bodies—feet, legs, hands, arms, eyes, nose, lungs, kidneys—function as a cooperative in order to survive. Let’s bring back the cooperative in the form of comrades sharing birth, aging, illness, and death. Then we will have plenty of time to create the best ecology.

“Conserving the Inner Ecology,” translated by Santikaro Bhikkhu, is excerpted with permission from the Suan Mokkh web site.