Masahito Hirose remembers it well: “a strong, white-blue flash… ships burning in the port… another sun appearing all of a sudden….”

In his email to me from his home in Nagasaki, he describes the morning of August 9, 1945, at 11:02 a.m., when the United States dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city. That day in Chicago, three days after the bombing of Hiroshima, Jan Bays came into the world. Now co-abbot of the Jizo Mountain—Great Vow Zen Monastery in Clatskanie, Oregon, Jan Chozen Bays (Chozen is her dharma name) says, “I realized I was led to become a Buddhist in the Japanese tradition partly because of the many people who died in Japan the day I was born.” Six decades after the blast, a simple idea of Chozen’s, sparked by the import she gave to the events around her birth, has become an international mission called the Jizos for Peace Project.

Jizo is the Japanese form of Indian Kshitigarbha (literally “earth womb”), one of the most revered bodhisattvas in the Mahayana Buddhist tradition. A beloved and significant figure in Japanese culture, Jizo is usually depicted—in the innumerable statues and shrines all over Japan—as a monk in simple robes with shaved head. Jizo serves as the protector of the dead, especially of those souls in the hell realms, and of travelers in all realms. He has particular popular relevance as the guardian of all children—born, unborn, and deceased. “Jizo is also said to be the patron saint of lost causes,” Chozen explains, “because Jizo never gives up.” For this reason, she says, Jizo was the perfect symbol for “the seemingly hopeless cause of world peace.”

With the Jizos for Peace Project, thousands of people—from twenty-five countries and every U.S. state except North Dakota—have created over 334,000 images of Jizo. Zen students, Christian congregations, neighborhood groups, children, and prisoners have rubber-stamped, traced, and drawn the Jizos onto thousands of cloth panels that are sewn into prayer flags, banners, and quilts. They join origami, wood, knitted, and clay Jizos in an August 2005 pilgrimage to Japan of thirty-five “ambassadors of peace” from Great Vow and other sanghas. The fourteen-day visit takes them to temples and Peace Day events in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, with Jizos for Peace displays there and at the Nagasaki Peace Museum. The Jizos are offered as an apology for the bombings, a memorial for the lives lost, and as prayers for peace in the future.

Chozen’s idea began modestly. Because she turns sixty on the sixtieth anniversary of the bombing of Nagasaki, she wanted to take sixty little Jizo statues to temples in Nagasaki and Hiroshima. “But then, in December 2002, I visited the Atomic Bomb Museum in Hiroshima and saw how the masses of people died, especially the children,” says Chozen, a pediatrician who specializes in the evaluation of abused children. Many Japanese children were vaporized at the blast’s epicenter, leaving only fragments of a lunchbox or sandal. She gazed at these displays of them, with a photo of and information about the child. “I knew then that I had to take one Jizo for every person who died from the bombings and the year that followed.”

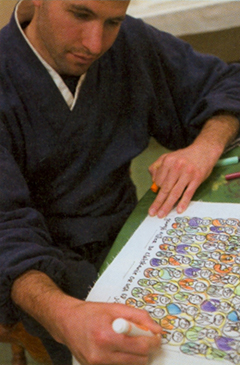

That’s 270,000 Jizos. How could she possibly manage that? Her friend, Kaz Tanahashi, a Japanese-American artist and peace activist, offered an approach based on the practice of copying the Heart Sutra. Done on translucent paper as a meditative practice, the copy is then dedicated to the memory of someone who died. At the monastery’s first Jizo retreat in August 2003, thirty-five people drew Jizos with colored markers on pieces of white cloth. Chozen encouraged them to think of someone who died in World War II and whisper the Jizo dharani, “Om-ka-ka-kabi-san-ma-ei-soha-ka,” a mantra that helps cultivate within one’s own heart the qualities of Jizo—optimism, compassion, courage, and peace—and allow them to manifest in the world.

The retreatants loved it. “They had come with their hearts in a state of agitation about the war in Iraq,” Chozen tells me. “But as they began working on these panels, instantly you could feel peace descend on the room.” The Jizos for Peace Project was born.

Great Vow residents and its sangha members continued to make Jizos, and others took the activity back to their communities to hold their own Jizo workshops. That summer Chozen presented the project to the American Zen Teachers Association’s annual meeting, and launched a website, www.jizosforpeace.org. Word spread and interest quickly grew. She soon knew that sending all those Jizos to Japan was indeed possible. “But then I thought, do they even want them?”

In December 2003, she, her husband, Hogen Bays, and Tanahashi traveled to Nagasaki to visit the Nagasaki Peace Museum, and speak with governmental officials and peace activists. But it wasn’t until their meeting with several bomb survivors (hibakusha), Mr. Hirose among them, that Chozen felt the power of the panels.

“At first, they were reserved, listening politely as I explained the project. But when I started passing around the panels and origami Jizos, instantly they became very animated, smiling and exclaiming over them. Then one of them said,” and I see tears filling Chozen’s eyes, “No one from America has ever apologized or brought us anything like this after the atomic bomb was dropped.’ When our hearts met in that moment, I knew there was no turning back. We had to do this.”

And now was the time. “That’s because we have enough distance from the war,” she says. “There’s a whole new generation that didn’t experience World War II directly, and so has moved past the enmity of it.”

Take Allison Yuko Krieger, novice priest and resident at Great Vow. One of her grandfathers worked on the clandestine Manhattan Project, responsible for the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The other also was an authority on the atomic bomb, and later led the team that developed Agent Orange. “I’m two generations removed, but I feel personally responsible,” she says. “As granddaughter, it’s important to do the reconciliation work that this project encourages.”

By spring 2005, the Jizos for Peace Project exceeded its goal by over 30,000 Jizos. Participants have responded to Tanahashi’s suggestion to include their name, age, where they live, and a photo of themselves on their panel. Doing so further personalizes it for others and symbolizes the individuality of each death. They also write the number of Jizos, and a message of peace that they project out into the world.

Krieger, as the official Jizo counter, is the only person who has seen every one of the Jizo renderings that have flooded the monastery’s mailbox daily. “It’s really mind-blowing,” she tells me, “all these prayers for peace from a huge diversity of people, with incredible, individual expressions and varying skill levels. But all with a simple desire for connection and peace.”

Says the director of the Nagasaki Peace Museum, Masakazu Masukawa, in a translated email to me, “I think [the] Japanese will evaluate this [exhibit] highly as a brave act of American citizens who wish for peace. Their presence teaches us the possibility of world peace, by calling for sympathy among people who wish for [it] and creating an alliance among these same people in the world.”

Concurrent with the museum’s exhibit, Jizos from Japan are being displayed during peace vigils at the Nevada Test Site and New Mexico’s Los Alamos National Laboratory, the birthplace of the atom bomb. Afterward, they will be enshrined inside Great Vow’s life-sized, hollow bronze Jizo statue, while most of the panels in Japan will be placed in Jizo peace shrines there. For the remaining Jizos, plans are under way for a traveling exhibition in the U.S. and overseas. There’s also talk of taking Jizos for Peace to other areas affected by past wars, and of initiating a Jizo order.

Concurrent with the museum’s exhibit, Jizos from Japan are being displayed during peace vigils at the Nevada Test Site and New Mexico’s Los Alamos National Laboratory, the birthplace of the atom bomb. Afterward, they will be enshrined inside Great Vow’s life-sized, hollow bronze Jizo statue, while most of the panels in Japan will be placed in Jizo peace shrines there. For the remaining Jizos, plans are under way for a traveling exhibition in the U.S. and overseas. There’s also talk of taking Jizos for Peace to other areas affected by past wars, and of initiating a Jizo order.

What began with a sixtieth anniversary of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki has become a timeless recognition of the universal. “As long as there are human beings, there will be war,” says Chozen. “But that doesn’t lift our responsibility to keep working for peace.” I ask her how the mind reconciles this contradiction. “It’s no different than other paradoxes we hold in Buddhist or Zen practice. We hold the tension of our being very human and fallible simultaneously with the awareness that we all have Buddha-nature and that each moment is perfect as it is. That’s what our practice asks of us—that we not give up hope, and keep working with great determination for peace.”

Buddhists and the Bomb

Reflections on Hiroshima and Nagasaki from six prominent American Buddhist teachers

“Devastating acts like the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki continue today, and that increases my resolve. ‘May I be free from enmity and danger.’ This first line of a lovingkindness chant has become more and more meaningful to me over the years. I appreciate more deeply than ever that enmity, whenever it arises in me, is a danger. It robs me of happiness and prevents me from being an effective agent for peace in the world.”

—Sylvia Boorstein, senior teacher,

Insight Meditation Society and cofounder, Spirit

Rock Meditation Center, Woodacre, California

“My understanding of life is the interconnectedness of it, so with the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, we’re talking about atrocities that happened to me, my body, at that time. The anniversary is an occasion to remember those atrocities. When I think of the word ‘remember,’ I think of ‘re’ and ‘member,’ a bringing back of parts of my body that I cannot forget. It’s like the phantom limb syndrome, but in reverse. Once you see that you do have an arm and it’s bleeding, you can’t ignore it.”

—Bernie Glassman Roshi, founder,

Zen Peacemaker Family

“We need to continually send messages to all corners of the world of no more Nagasaki, no more Hiroshima, and no more war. I think people do not have enough information about nuclear war, particularly in this country, a nation with nuclear weapons. There’s a lack of morality, and that’s why we are still manufacturing these weapons. I cannot convert others, but I can work on my conviction to make an effort to abolish nuclear weapons.”

—Brother Gyoshu Utsumi,

Nipponzan Myohoji, Atlanta, Georgia

“Something that happens anywhere on this planet affects everyone everywhere. Nothing happens in isolation. Just as we’re all interconnected, the bombings happened to each of us—you, me, all of us. When we drop the boundary between self and other, we become more intimate with this event.”

—Genpo Merzel Roshi, abbot,

Kanzeon Zen Center, Salt Lake City, Utah

“The bombings are an unparalleled atrocity that is so regrettable. It is something the American people should repent versus support as something that ‘won the war’ (which is how it’s been sung in our nationalistic and chauvinistic mythology). To repent is to have a clear awareness of the wrongs that have been done, and not let anything within my province allow them to happen again.”

—Dr. Robert Thurman, department chair,

Jey Tsong Khapa Professor of Indo-Tibetan

Buddhist Studies, Columbia University, New York City

“What matters is a profound sense of commitment to peace, followed by actions that support the end of the development, construction, and proliferation of all weapons of mass destruction. The sixtieth anniversary of the dropping of the atom bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki reminds all of us of the horrors of destruction, and that in sixty years we seem to have learned little. It also reminds us that the tragic consequences are not over in a day, nor in decades.”

—Joan Halifax Roshi,

Upaya Zen Center, Santa Fe, New Mexico