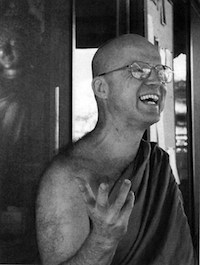

Thanissaro Bhikkhu, 48, has lived as an ordained monk in the Thai forest tradition for twenty-two years, fourteen of them in a tiny meditation monastery in the jungle of southeastern Thailand, where he cared for his ailing teacher, often around the clock, for weeks on encl. Today, he is abbot of the Metta Forest Monastery in Valley Center, California, a handful of spare buildings and shady meditation paths peppered through a mountaintop avocado grove, a forty-five minute drive into the hills north of San Diego. Founded eight years ago with the help of an American benefactor and a Thai teacher, Ajaan Suwat, the monastery now houses six monks and a steady stream of students—a small size that helps keep the personal contact “because the teaching relies on that contact, day in and day out.” Metta depends for its survival mainly on the dana, or generosity, of the substantial Thai community in southern California.

Born Geoffrey DeGraff, he grew up “a very serious, independent little kid” first on a potato farm on Long Island, New York, and later in the suburbs of Washington, D.C. At Oberlin College in the early 1970s, he eschewed campus political activism because “I didn’t feel comfortable following a crowd.” For him, the defining issue of the day wasn’t Vietnam, but a friend’s attempted suicide. When the opportunity came to meditate in a religious studies class “l was ripe for it. I saw it as a skill I could master, whereas Christianity only had prayer, which was pretty hit-ormiss.” He traveled on a university fellowship to Thailand and after a two-year search found a forest teacher, Ajaan Fuang, who insisted that his scholarly American student put his books aside. After a brief stay with the teacher was cut short by malaria, he returned to the U.S. to weigh the merits of academia and monasticism. While attending a panel on Buddhist studies, however, he decided definitely that practice was better than theory.

Thanissaro Bhikkhu follows the path of the Kammatthana forest monks—a path based on the Vinaya, the Buddha’s monastic code, that appears strict in the extreme to outsiders: he doesn’t handle money and cannot ask for anything that is not freely offered; he eats only one meal a day, before noon; he does not spend time alone with a woman, or drive. The author of Wings to Awakening and The Buddhist Monastic Code, among other books, he has translated many Buddhist texts from Pali and Thai, including, most recently, the Dhammapada. The interview was conducted by Mary Talbot at Metta Forest Monastery.

If the Buddha got enlightened without all the rules, why, in this tradition that claims to be closest to the life of the historical Buddha, are there so many rules for monks?

The Buddha had already internalized the principles of the dharma. Rules were really a response to monks who got out of line. They’re also useful as warning lights—when you’re tempted to break a rule, you have to slow down and examine your motivation. Often you find there are subtle levels of greed, anger, or delusion that you didn’t see at first.

These days, do you have problems with the rules?

My main problem is not wanting to inconvenience or offend people, and the rules can do that. But what always keeps me in line is a strong sense of indebtedness to a tradition way bigger than I am. In my early days as a monk, I didn’t think much of the Vinaya. They were just rules I had to put up with if I wanted to stay in Thailand and meditate. But then I began to see that every time something went wrong in the community, it was because someone had broken a rule. I also began to see the rules as protection for me in my practice.

Some Theravadin monks in the West have decided to adjust certain rules for expediency’s sake. Take the example of riding in a car driven by a woman with no one else present. Why wouldn’t you bend that rule for the sake of convenience?

So the people who come after us won’t have to learn the hard way that this was a wise rule, so they won’t have the uphill task of trying to revive it after it’s dead and gone. Besides, I can always walk. I think what’s hardest here in the West is simply the idea of rules.

Theravada shares a lot of the same rules with all other Buddhist traditions. But the rules that relate to women suggest—at least to Westerners—that this is a sexist, troublesome tradition.

The hardest rules are the ones about women, because they seem to imply that there’s something wrong with women. But if you go back to the origins of the rules, you find that the problem was almost always the monk. The rules are basically a reminder that the relationship between a teacher and a student of the opposite sex has a lot of potential for being abused. And when it does get abused it’s devastating. It’s not that monks are bad, or women are bad, but this particular situation has to be handled very carefully. So the rules are like flags to remind you that overstepping the boundaries starts with the tiny things and spreads to the hard stuff. As the Buddha says, “Let’s stamp out the fire when it’s still small.” You also have to remember that Buddhist monks aren’t kept behind walls. They’re out wandering around, so the only way to maintain boundaries is through rules of etiquette—the monastic code. In the West, we tend to forget that etiquette is a useful thing. I’ve been reading Miss Manners’s latest book [laughs]. She makes the point that the less we pay attention to etiquette, the more we have to rely on the hand of the law, which is a very heavy hand. It comes down with a lot of brutality. It can’t deal with finesse. So the monks’ guidelines are just that: guidelines that say in a certain situation, you have to be very circumspect about how you act.

If a monk is really enlightened, does he need to follow the rules?

Monks who have finished following the path say they still abide by the rules as an example. There’s a really great passage about Maha Kassapa, one of the Buddha’s foremost students, who’s completely finished his job as a monk and is still living in very severe conditions out there in the forest. And the Buddha says, “Why are you doing this? Why don’t you come and live in one of my monasteries where it would be a lot more comfortable for you?” Maha Kassapa says, “Well, one, I like living in the forest and, two, this is my gift to future generations.” The example. People ask why Theravadin monks are so attached to the path. Well, those who’ve benefited from the path see what a valuable thing it is.

Were you always a traditionalist?

I liked finding a tradition where you could be radical. My mother held me up to very high ideals and stringent standards. And as I grew up, I found that this made me something of a social misfit. Traditional role models seemed too much of a sell-out, and nontraditional ones were too flaky and self-indulgent. With Ajaan Fuang I found someone who lived up to high ideals without any pretense or hypocrisy—someone who built on the wisdom of a long tradition and yet was free to be very much himself. I wavered for quite a while about whether l could take on those ideals, too. But then I realized l couldn’t live with myself unless l at least gave them a serious try.

There’s such a variety of Buddhist paths, and you’ve signed on with the one that seems the most conservative. But as you say, from another view, it seems really radical. It certainly puts you out of sync with your own generation of American dharma teachers.

Somebody has to be out of sync [laughs]. Most of the vipassana movement in this country offers a very stripped-down version of Buddhism. It’s presented in the context of modern psychology, where a meditation technique becomes an extension of therapy. That places a limitation on what you expect from meditation. The Buddha’s awakening was about confirming larger truths, not simply about gaining a greater sense of connection or of ease.

What if people only want a greater sense of connection or ease?

That’s fine. That’s called domesticated Buddhism, and it’s always going to be there. Thais like ceremonies where they can make merit for their dead relatives; Americans like taking retreats where they can feel connected with the world. They’re coming from a similar impulse. But please don’t present just that much as the whole of Buddhism. There are books that will tell you that the sign of successful spiritual practice is the ability to have meaningful relationships—nothing about nirvana. But there will always be people who want more and Buddhism should be there for them.

Are “meaningful relationships” and “universal interconnectedness” related? I heard a student ask you about the feeling of “universal interconnectedness” that sometimes arises in meditation, and you said that was just a phase you go through. What did you mean?

The point of concentration is to become one with the object—the breath, the body, whatever. That gets you into a really solid state of feeling at ease with that particular aspect of your experience. As it develops, your old preconceived dividing lines disappear and there comes a sense of everything being interconnected. But if you observe that sense of oneness long enough, you begin to see that it’s made up of layers of activity: feelings of oneness, mental labels that say “oneness,” that sort of thing. They’re like layers in an onion. The layers are separate, but the dividing lines between them aren’t where you thought they were. You begin to realize that you’ve bought into the whole schmear, and that it’s really oppressive. You want to get out. It’s only when you learn how to peel through the layers without aversion or attachment that things open onto something else entirely. Another dimension. Total, absolute freedom. When you come back from just a glimpse of that, you come with a whole new understanding of the activity of the mind that ties us into the stress and suffering inherent in space, time, and the present. You see interconnectedness in a new light, that it’s nothing to celebrate. Everybody in here is suffering together. When you realize this, you can never do anything intentionally to harm anyone ever again.

Are you emphasizing detachment over compassion? Can a distinction be drawn if they’re part and parcel of the same state of awareness?

Theravadins would say, Why advertise the compassion if it’s naturally there? Detachment could use some better press, though, because people think it’s averse and selfish. It’s not.

Is the dharma so fragile that is has to be safeguarded so zealously?

The dharma isn’t fragile, but the teachings themselves are. Extremely fragile. Some people say that Buddhism embraces impermanence, and therefore we should have no problem with the dharma becoming impermanent. But Buddhism doesn’t embrace impermanence. It teaches you how to deal intelligently with impermanence, without suffering. That’s a very valuable teaching, and you want to do what you can to keep it whole. But speeding up changes in the dharma because we know they’re inevitable is like speeding up the destruction of the environment because we know the sun is going to burn out someday anyhow.

Since coming back to the West, what are the biggest problems you’ve seen in people’s meditation?

Low self-esteem. Low resilience. An inability to admit mistakes. These are all connected. People grow up here with a sense of self-hatred, and when you take that into your meditation, it makes it very difficult to be patient with things as they come up. You identify anything that’s negative as being a sign that there’s something wrong with you as a person.

The media, too, are not all that helpful. Their basic message is that what’s important in life is what’s happening to someone else, out there—not what we’re doing, here, right now. Buddhism tells us that there’s part of your mind that seriously wants true happiness, believes in the potential for true happiness, and is willing to do what is necessary. We can’t get sucked up into the messages that tell us to ignore the fact of old age, illness, and death, and to ignore the meaninglessness of life as we ordinarily live it.

To go back to an earlier point, aren’t the teachers who are offering a more contemporary form of Buddhism concerned with illness, old age, and death, too?

Yes, but they want to look at illness, old age, and death in a life-affirming way, which is hardly the Buddha’s take non the matter. He wanted us to rub our noses in these things so that we’d feel motivated to look for a way out—beyond the cycle of life and death entirely. Our basic problem is that we tend to take his teachings out of context and squeeze them in to our own limited worldview. We take one segment of the tradition and say, “This is what it’s all about. Everything else is cultural trappings.” We’re more ethnocentric than we think, so we miss out on a lot that the dharma has to offer. This is why we need a wilderness Buddhism: to take off our blinders and get us out of the prevailing culture.

What’s the advantage to introducing a wilderness tradition in the West?

There’s a fringe culture here of people going out and trying to live an honest life like Thoreau, but they don’t have a wisdom tradition to fall back on. So everybody keeps reinventing the wheel.

And that’s where the teacher comes in?

Right. It ‘s too easy to go alone in to the wilderness and co me up with some pretty weird notions. You need to be in touch with people who’ve been through the wilderness experience and have come out with a wise set of priorities. Not that you’re trying to clone their priorities, but good teachers ask you the questions that help you test your own. That was stressed in my training: that we’re not here just to conform blindly to the texts. We need to develop the dharma in our character. That’s why my teacher would put me in situations where l’d have to be quick or use my ingenuity or test my powers of observation, getting me used to dealing with situations that were physically demanding and sometimes dangerous. The forest demands more out of you—unlike a monastery like this, where there’s a schedule, and you’re used to “Now’s the time to rest, and now’s the time to do this.” You’ve got to find these reserves in you, and you’ve got to trust the fact that they’re there.

How does offering something to rely on encourage greater sacrifices?

It’s like working your way up a ladder to a roof. You have to hold onto a higher rung before you can let go of a lower rung. Only when you’re safely on the roof can you let go entirely. A monk once said to Ajaan Mun, “I’m living in Bangkok, surrounded by educated people, but I can’t find anyone with answers to my problems. What do you do when you’re out in the forest with no me to turn to?” And Ajaan Mun said, “I hear the dharma twenty-four hours a day, except when I’m asleep.” Both through watching your own actions and seeing what’s around you, there’s always a dharma lesson. But the ability to stay tuned into the dharma requires a strong mind so that you don’t get tuned into something else. It’s the combination of having a good friend and a good environment that gets you started in the right direction.

And time to practice?

Yes. Ajaan Fuang used to say that most people live a life divided up into times—time to eat, time to work—with never any sense of timelessness. The scariest part of my initial training as a monk was that every day I had an entire day with no busywork to protect me from myself. At first you feel hemmed in by all the rules and restrictions. Then after that initial reaction, you realize how wealthy you are in terms of time. There’s a much higher standard: It’s not “Are you doing enough work to pass school or please your boss?” It’s an infinitely bigger undertaking: “Are you going to be able to end suffering?” And if you don’t get to the end, you’re falling short! When your life isn’t divided into times for this and times for that, you have a much more spacious sense; you’re capable of a lot more than you thought you were. And that’s the good news of Buddhism—that you are capable of much more than you ever imagined. You can end suffering. It’s true. When you’re given all this free time, you no longer have any excuses. And once you learn to take advantage of that, you wouldn’t trade it for anything else.

Thanissaro Bhikkhu, 48, has lived as an ordained monk in the Thai forest tradition for twenty-two years, fourteen of them in a tiny meditation monastery in the jungle of southeastern Thailand, where he cared for his ailing teacher, often around the clock, for weeks on encl. Today, he is abbot of the Metta Forest Monastery in Valley Center, California, a handful of spare buildings and shady meditation paths peppered through a mountaintop avocado grove, a forty-five minute drive into the hills north of San Diego. Founded eight years ago with the help of an American benefactor and a Thai teacher, Ajaan Suwat, the monastery now houses six monks and a steady stream of students—a small size that helps keep the personal contact “because the teaching relies on that contact, day in and day out.” Metta depends for its survival mainly on the dana, or generosity, of the substantial Thai community in southern California.

Born Geoffrey DeGraff, he grew up “a very serious, independent little kid” first on a potato farm on Long Island, New York, and later in the suburbs of Washington, D.C. At Oberlin College in the early 1970s, he eschewed campus political activism because “I didn’t feel comfortable following a crowd.” For him, the defining issue of the day wasn’t Vietnam, but a friend’s attempted suicide. When the opportunity came to meditate in a religious studies class “l was ripe for it. I saw it as a skill I could master, whereas Christianity only had prayer, which was pretty hit-ormiss.” He traveled on a university fellowship to Thailand and after a two-year search found a forest teacher, Ajaan Fuang, who insisted that his scholarly American student put his books aside. After a brief stay with the teacher was cut short by malaria, he returned to the U.S. to weigh the merits of academia and monasticism. While attending a panel on Buddhist studies, however, he decided definitely that practice was better than theory.

Thanissaro Bhikkhu follows the path of the Kammatthana forest monks—a path based on the Vinaya, the Buddha’s monastic code, that appears strict in the extreme to outsiders: he doesn’t handle money and cannot ask for anything that is not freely offered; he eats only one meal a day, before noon; he does not spend time alone with a woman, or drive. The author of Wings to Awakening and The Buddhist Monastic Code, among other books, he has translated many Buddhist texts from Pali and Thai, including, most recently, the Dhammapada. The interview was conducted by Mary Talbot at Metta Forest Monastery.

The Thirteen Thudong or Austere Practices

Thudong, from the Pali dhutanga, literally means a “way of polishing off” mental defilements. Some of the thirteen practices are mentioned in the Pali canon, but others were not codified until the fifth century in the Theravada text known as the Visuddhimagga, or Path of Purification. It is up to each monastic how many to follow and how often to practice each one.

1) Wearing robes made out of cast-off cloth

2) Possessing only one set of three robes

3) Going out for alms*

4) Not omitting any houses on the alms round (if a monk knows a family to be poor and to offer poor food, he must not skip their home)

5) Having only one meal a day (not before dawn and not after noon)*

6) Eating out of the alms bowl (food may not be arranged on separate plates)*

7) Not accepting food presented after the alms round (this rule is based on the idea that food that comes later tends to be better)*

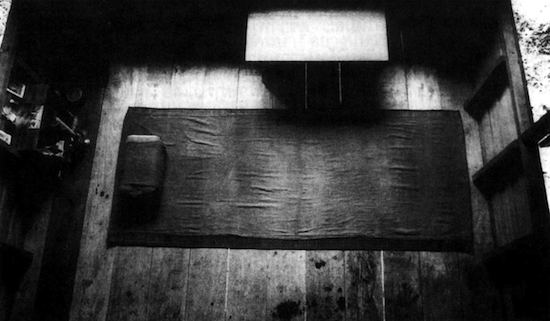

8) Dwelling in the wilderness (a monastic may live in a hut in the wilderness)

9) Dwelling under a tree (this is considered an added hardship)

10) Staying in the open air (again, an added hardship)*

11) Visiting or staying in a cemetery

12) Being content with whatever shelter is provided

13) Not lying down (monks who take on this practice sleep in the sitting posture for days or months at a time)

*In the Kammatthana tradition, the five practices marked here with an asterisk are adhered to assiduously.