I gaze up at a galaxy of cartoon stars. Turning my head to the right I see five checkerboard platforms linked by staircases and studded with simple geometric pillars and arches. Pressing a button on my hand control, I “fly” toward this gameboardlike space station, zooming closer and closer until I’m “walking” on an upper platform. Human and inhuman enemies are hiding.

Darting around, weightless, in a bare, bright, mechanically uniform world, I try to steady the cartoon gun extended in the cartoon hand before me. The scene shifts with my gaze, though there’s a tiny perceptual lag that makes me feel like I’m trying to focus underwater. A geometrically muscular cartoon man in blue pants appears.

I squeeze the trigger on my hand control. Rocket grenades fall in slow white arcs.

“Time to die,” intones a cold computer voice. Amidst booming quadraphonic heartbeats, squawks and screams, I try to aim my gun but a huge, lime-green cartoon shadow descends and engulfs me. The pterodactyl sweeps me higher and higher into space until I explode into brightly colored confetti and vaporize into the computer-generated space that William Gibson called “cyberspace” in his seminal 1984 novel Neuromancer (Doubleday/Dell).

Back in the everyday world, I’m standing on a small circular platform at the South Street Seaport in downtown Manhattan. I’ve just finished playing “Dactyl Nightmare” on the Virtuality system, one of the first mass-market applications of the technology called virtual reality (VR). So far, even in the most sophisticated systems the simulations that VR can produce are crude, slow, and gaudily superficial. They play to the eyes and the ears and the jumpy, calculating “monkey mind”—as the Buddhists call it. Yet, in spite of these limitations—or perhaps because of them—virtual reality may transform, in the next decade, the way we construct science, architecture, engineering, education, medicine, communications, and art.

Virtual reality yokes human attention to a computer mind in order to generate three-dimensional worlds that a human being can inhabit. This extraordinary technology has attracted interest particularly from Buddhists because of the claim that it mirrors and amplifies the way we build up illusory worlds in our own minds. And within the whole spectrum of Buddhist traditions, it provokes parallels with those traditions that employ visualization practices.

“I think the cyberspace experience is destined to transform us because it’s an external mirror of something that Buddhists have always said, which is that the world we think we see ‘out there’ is an illusion,” says Howard Rheingold, author of Virtual Reality (Touchstone, 1992). “We build models of the world in our mind, using the data from our sense organs and the information processing capabilities of our brain—only we’re hypnotized from birth to ignore and deny it.”

Can virtual reality really make it easier for people to penetrate the nature of mind? Or will it just help us drown in our peculiarly American dukkha (suffering), or unsatisfactory experience, by expediting our catastrophic break with nature and the larger world of humanity, which isolates us in expensive little electronic capsules?

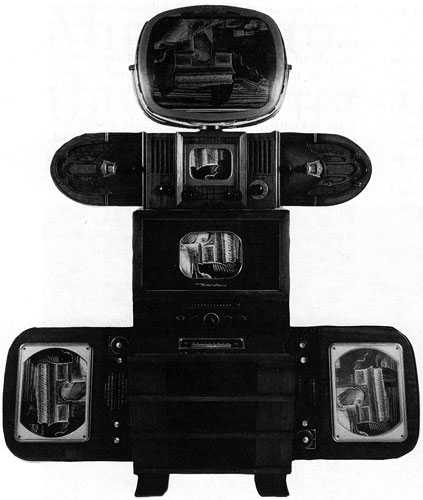

As a cybernaut you must wear an uncomfortable plastic helmet that shuts out the outside world and makes you look vaguely like a human fly. Each eye is covered with a tiny liquid-crystal display screen that feeds you continuously updated, computer-generated imagery—a slightly different perspective for each eye. You are not watching a pre filmed movie but participating in an ever-changing, real-time computer world. A flexible DataGlove threaded with fiber-optic cables registers your hand position and pressure, creating the illusion that you are grasping virtual objects.

Virtual reality is a complex set of devices that were the result of developments in computer graphics, personal computers, and other sensory devices. Many breakthroughs were made by maverick visionaries working outside the mainstream, yet research into virtual reality has been funded and nurtured by NASA and the military as well as by major universities including MIT and the University of North Carolina. No single pioneer of this emerging technology stands out, though many computer scientists cite the work of Ivan Sutherland, who in the sixties built the first head-mounted display—virtual reality goggles—and invented a groundbreaking computer-graphics program called SketchPad. But it wasn’t until the mid-eighties that the potential of VR as an all-encompassing experiential universe became apparent.

Today, one of the most articulate champions of VR is Jason Lanier, CEO of VPL Research (a leading VR equipment company): “Virtual reality,” he says, “is a technique for creating simulated experience, or rather, an experience of a simulated external world. It does this with the help of computerized clothing that covers your sense organs.”

At the moment, that clothing is rare and costly, and Lanier’s firm is reportedly making a fortune marketing black-rubber head-mounted displays called EyePhones and DataGloves that measure the position and movement of your fingers. Within ten years, however, virtual reality is going to become sleek and cheap, and it’s going to be everywhere.

Soon, for example, a surgeon will be able to practice removing a tumor or repairing a heart valve by putting on goggles and a glove. A perfect computer-generated simulation of a body will appear, and by simply grasping the scalpel and cutting, a new technique called force-feedback will allow the doctor to feel the liquidness of the patient’s blood and the resistance of tissue and bone.

Still, these simulations of VR are theoretical constructs. They look realistic but they aren’t “truthful,” and they raise serious practical and spiritual questions.

For example, training doctors or scientists to trust tactics they learned from simulations rather than real-world practice may further blind them to the unique and interdependent value of each body, each molecule. The map is not the territory. A cartoon body is not a life. From a Buddhist point of view, the scientific visualizations of VR could operate either as a great tool for healing or as just one more dazzling force in the Western world that will conspire to reinforce smug intellectual certainties and inhibit compassion and real spiritual search. Clarity about the nature of the medium is crucial, because VR will soon offer forms of entertainment so all-absorbing that one observer has called them “samsara squared.” Mattei has already brought out the “Power Glove,” an $89 toy version of the $8,800 DataGlove II. And it enables its wearers—usually kids—to box with virtual opponents and to cause virtual death and destruction with a wave of their “real” hands. Meanwhile, Lanier and MGM have a deal to develop” virtual movies,” or “voomies,” using telepresence to bring a comic “changeling” into a theater space to keep you laughing. And, in the ultimate application of computer self-satisfaction, eventually you may be able to climb into a full-body contact suit and indulge in “teledildonics”—virtual sex between one or more consenting simulations.

“I think the best way to view virtual reality, especially for people who are interested in Buddhism and their own spiritual development, is as a Jungian sandbox,” says Thomas Zimmerman, who as a young MIT graduate invented the prototype for the DataGlove with a brown cotton work-glove and $10 worth of parts. “You have to watch how people are using VR and see how what they do with it reflects what they’re trying to achieve.” Zimmerman co-founded VPL Research with Lanier and helped develop a perfected DataGlove II before signing the patent over to VPL Research and moving on to explore the integration of sound and music with dancers’ movements.

Now thirty-five, Zimmerman, who has a strong interest in Buddhism, is torn between his understanding of the creativity and genuine scientific exploration that VR can make possible and his disillusionment with the way people have used this technology to date. “So far, it has been used mostly for exercising control and perpetrating violence.”

Virtual Reality and Buddhism

Buddhism suggests that in order to realize emptiness, we must emerge from the small, dark world of our own egos into the big world of all other living beings seeking happiness. And even more is required.

Along with emptiness, according to Robert Aitken in an essay called “The Body of the Buddha,” one must experience oneness and uniqueness—these three elements of Buddhahood are called the “Three Bodies of the Buddha”: the Dharmakaya, the Sambhogakaya, and the Nirmanakaya. Complementary to the emptiness that is the natural law of things, writes Aitken, there is fullness or oneness, the sense that “the whole universe is a vast, multidimensional net, with each point of the net a jewel that perfectly reflects and in fact contains all other jewels.”

And finally, we must also experience individual uniqueness: “The earthworm and the nettle are individual; no other being will ever appear like this particular earthworm, this particular nettle.”

The Buddhist adepts say that we must practice in a way that engages and balances our body, mind, and emotions—our inner and outer worlds. And this threefold vision of reality can never be accomplished by the intellect alone.

“Without practice, philosophy is superstition,” writes Aitken. He goes on to explain that Zen practice—and most other forms of Buddhist practice—involves “coordination of body, brain, and will, in directed meditation.” If this is true, then emptiness in all its fullness and uniqueness—the Three Bodies of the Buddha—can never be glimpsed by strapping miniature TV sets over our eyes and pretending to blow away lime-green pterodactyls.

Recently, the Dalai Lama said that he would sum up the Buddhist understanding of the nature of reality in this essential line from the Heart Sutra: “Form is emptiness and emptiness form.” Continuing, he explained that emptiness means interdependence, “and interdependence means emptiness of independent existence.” The Dalai Lama stressed that “the correct understanding of the subtlest level of interdependence—that of the interdependence of things and conceptual constructions—has more to do with maintaining the balance of the outer and inner world, and with the purification of the inner world.”

It’s tempting to think that we can awaken to the nature of reality through electronic means. Picture an architect walking in a virtual room in a virtual building that he is planning. Suddenly, he remembers that he is in a computer simulation. Alarm bells go off in his head. “Everything I’m seeing is an illusion,” he thinks. He walks a little farther on his computer-linked electronic treadmill, experiencing the sensation that he is walking down a long hall. “Come to think of it,” he muses, “I’m always seeing mental constructs, mere illusions, and mistaking them for solid things.” The real trick, however, is inspiring this clever architect to see that it is his attachment to these illusions that leads to suffering. In order to go deeper than a fleeting intellectual observation, he is going to have to acquire a taste for the stillness of meditation, for devotion, for surrender. Who knows exactly what it takes to awaken such feelings, such a sense of sacred importance, in a man or woman? Still, it’s a safe bet that it’s not going to happen while you’re wearing a head-mounted display, because in VR, the medium is the real message, and the medium is overwhelmingly heady.

“It drives you up into your head,” says Zimmerman. “There’s a heavy emphasis on external stimuli, on visuals and sound. What it’s doing is enhancing the dukkha, even though it is interactive. It appeals to the excited mind rather than to the contemplative mind.”

Yet while you lose deep sensation and feeling in VR, you make up for it with the ability to do things in a computer-aided mental space that you could never do in the “real” world.

Soon you will be able to “telepresence” anywhere in the world. Picture a virtual sangha flying to Mount Kailas. We could walk around the mountain and spend the night meditating in Milarepa’s cave. Only there would be no washed-out roads to contend with, no broken-down Tibetan bus, no cold feet and cold tsampa, no fights and fatigue. Consistent with the limitations of VR, there would be no sense of smell or taste on our trip, no sensation of our hearts beating or of our breath belabored by heights, no sight of darkness gathering. There would be no sense of the physical presence of the ancient mountain, no sense of its rootedness, no sense of the earth.

In virtual reality, we will never be able to read what John Muir called “the inexhaustible pages of nature … written over and over uncountable times, written in characters of every size and color, sentences composed of sentences, every part of a character a sentence.” This is the contention of Bill McKibben in his book The Age of Missing Information (Random House, 1992). McKibben shows how TV has cut us off from an awareness of the cycles of nature, how it has coarsened our senses and blunted that more subtle ability to feel ourselves in context. McKibben claims that the ever-expanding capacities of virtual reality are efforts to compensate for what’s missing. “They are attempts,” he contends, “to overcome through more technology the frustrations of living in an electronic world.”

More troubling, perhaps, is that technology itself now so thoroughly defines “life” that we no longer know why separation from nature matters so much.

But it is in nature and not in electronic reality—in the encounter with cycles and silences—that reaffirms that we are active and singular participants in a great oneness that is, in every aspect and every moment, unique.

“Smell of autumn/heart longs for the four-mat room.” Could Basho have realized this moment under the cartoon stars?

“We have to communicate with reality: otherwise there is no reality,” writes Chogyam Trungpa in Journey Without a Goal (Shambhala Publications, 1981). “Of course reality is real, but our contact with reality is through our sense perceptions, our body, and our emotions—the three mandalas. The three mandalas are what meet, or mate, with reality.”

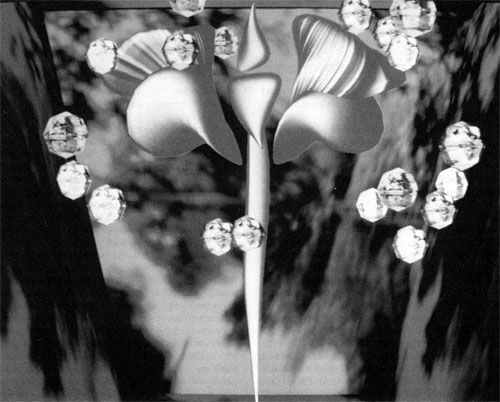

Although Trungpa is speaking of tantra, all forms of Buddhism teach that we must eventually make contact with our real bodies and our real emotions as well as our minds. That’s why a computer-visualized deity could never pack the same psychological wallop. Something has to happen from the inside out.

“The goal in all tantric traditions,” Trungpa explains, “is to bring together the lofty idea, the jnanasattva of humor and openness, with the samayasattva, which is the bodily or physical orientation of existence. The practice of visualization is connected with the practice of combining the jnanasattva and the samayasattva.”

But some experts believe that VR is the harbinger of a time when the body can be dispensed with completely—when presence will be defined as an accumulation of data in a given mental space, having nothing to do with human warmth or understanding. Still, enthusiasts like Lanier insist that VR will break through the numbing tyranny of TV and usher in a new era of creativity and communication.

At a recent “Cyberarts” convention, Jason Lanier spun a dramatic scenario about life in the near future, when virtual reality “will turn into the next generation telephone.” He predicted that glasses and a glove will produce virtual shelves lined with fish tanks. But “instead of fish, the tanks contain little people running around in various scenes.” In each scene, Lanier explained, people will be playing football or shopping or looking at real estate. “These little people are all real people. Just like you, they’re networked together, having group experiences from their homes. When you put your gloved hand into a tank, the tank gets very large and surrounds you, and you fly down into the scene and join the group.”

But being present to one another is not an option. We’re going to be brightly colored, generic cartoon characters, and will unplug whenever we get bored or scared or fearful or things get difficult. Any of the inevitable discomfort that surfaces in the face of intimacy, sex, and death—more than ever—can be subsumed by desire and the illusion of choice.

The consensus seems to be that the proper and ethical use of VR, from a human as well as a Buddhist standpoint, seems limited to a scientific instrument, as a means to extend human intelligence and consciousness. “Why do we need even more encompassing, more entrancing entertainments?” asks Zimmerman. “Why go even further away from the natural world precisely at the time when we need to draw closer to nature?” There are some even more chilling VR experiments actually in the works. For example, the Navy has developed the “Green Man,” a tele-operated drone soldier that can move like a human being. Similarly, psychologist Nathaniel Durlach is trying to link specialized “slave robots” to human perception in order to increase our strength and knowledge to superhuman levels. By linking up with one micro-robot, we could swim in our own bloodstream. By hooking up to another, we could experience what it’s like to hear like a dog. The same technology could help a quadriplegic walk or make a firefighter invincible. Durlach’s applications are all to the good, of course, but his research could also result in an army of specialized “Green Men” with X-ray vision that walk through concrete walls or swim in our bloodstreams. Clearly, motivation—right or wrong—will be the key.

Virtual reality is changing too quickly to predict its outcome. Some people, showing impressive amounts of time-honored American tent-show revivalist fervor, see VR as a miraculous vision machine, an electronic version of the caves at Lascaux, that can expand our consciousness and help us to live in a hyper-complex world. For others, it will be an immersive, interactive TV that can help bury us in our own selfish ignorance and aggression.

Lest we be too shortsighted and fearful, a forthcoming book called Gentle Bridges: Conversations with the Dalai Lama on the Science of Mind (Shambala Publications, 1992) includes these speculations by the Dalai Lama about whether or not computers can attain consciousness: “I can’t totally rule out the possibility that, if all the external conditions and the karmic action(s) were there, a stream of consciousness might actually enter into a computer.” He even considers it possible that a scientist “who is very involved his whole life” with computers might be reborn in a computer—”then this machine which is half human and half machine has been reincarnated.”

One day, after many computer ages have passed, a great RoboBuddha may arise to help us. In the meantime, it seems wisest to see virtual reality as an empty mirror—an extraordinary tool, but just a tool—that magnifies what we already are: escapists, scientists, addicts, artists, and bodhisattvas too.