Because of the confluence of many forces—among them a Contemplative Practices Fellowship offered under the auspices of the American Council of Learned Societies for the design of a new course to be taught in spring 2000—I find myself—a fat, inexorably aging, California laid-back, funky, left-leaning, dreadlocked Aframerican woman poet—teaching this semester at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. I have two sections of an upper-division course on poetry and meditation. This is the weirdest thing I’ve ever done. West Point is integrated and, since 1976, coeducational, but it still seems to me to be the antithesis of the cultures suggested by my physical and intellectual presence. Surrounded by uniformed young people in tiptop physical condition, I feel as visible and as out of my element as a cockatoo in a flock of ravens, an aborigine in the citadel. Most of the other courses at West Point are taught by Army officers. Their classes begin with the section leader calling the cadets to attention and reporting absentees, then the teacher salutes and tells them to take their seats. My classes begin with five minutes of silent meditation in a dark room. Then we embark on the hour’s discussion of poetry. My cadets struggle to fit the required fifteen minutes of daily meditation into their overpacked schedules, while I struggle to hold on to the belief that I’m teaching them something meaningful and relevant to their lives: to accept and understand the multiple contradictions of their world.

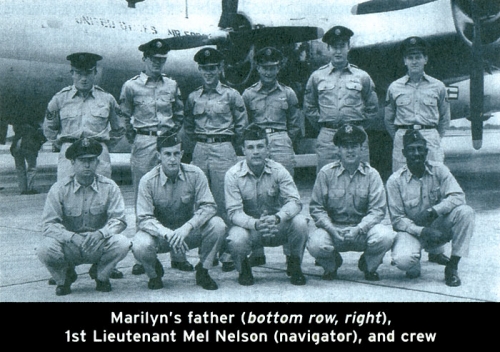

I grew up in a military family. My father spent sixteen years in the Air Force as a B-52 navigator. As a protected and proud child, a nomad among nomads, my status at elementary and junior high schools was determined more by my dad’s rank than by our race or my character. My father was an officer, always one of a handful of black officers on any base, and he was thus treated with official respect. Subordinates, black and white, saluted him and called him “Sir.” While we could not ignore the hellish response to the Civil Rights Movement unleashed on the civilian world of the 1950s, we lived on Air Force bases and were effectively insulated from explicit discrimination. Our car was saluted every time we drove through the gates. The military world, my father’s world, was the orderly cocoon in which I grew a poet’s wings. I expected, since I grew up around men in uniform, that my transition to West Point would be smooth and painless, a return to my father’s world. Instead, West Point has shown me how firmly my mother rejected military values, and the lengths to which she went to keep her children from being too much indoctrinated with the authoritarian ethos of military life.

Sitting with the principal of the West Point Middle School on the morning I enrolled my daughter as an eighth grader, I remembered that military children are trained to respect adults. Each of the children who came into the office that morning ma’amed the school secretary and sirred the principal. My daughter, of course, did not. Nor did my sister and I, when we were children. Mama insisted we not do so. Indiscriminately applied honorifics were for her a symbol of slavery and the South. She was born and raised out West, in the all-black town of Boley, Oklahoma, and her life was imbued with Boley’s radical pride. We were under her strict orders never to call anyone sir or ma’am, unless we felt they deserved our respect. I’ve raised my own children with that habit of intentional respect, so I’ve noticed with some embarrassment that at West Point, adults look at my daughter with slightly raised eyebrows when she responds to their questions with a teenagerly “yeah.” My mother would have been proud of her. She was an artist, a gifted musician. She raised my siblings and me in the counterculture, to be artists (my sister an actress/director; our brother a jazz musician) rather than soldiers. Mama taught us to question authority—even our father’s authority. We straddled two value systems in our household, between Daddy’s Saturday morning white-glove inspections of our rooms and Mama’s lighthearted refusal to take rules seriously. While he checked one corner of the room for lingering traces of disorder, she might wink and slide an overlooked dust-bunny under the rug. If she ever called anyone sir, she did so with the same twinkle of merriment with which she sometimes saluted our father. I am “ma’amed” by my West Point students and find that fact both amusing and curious. At first I took the cadets’ addressing me as ma’am to be a sign of respect. However, I soon realized that it is a rote response, like their saluting eagles on a colonel’s shoulders. Under this habit of verbal respect, my cadets, most of them white males, many of them Southerners, can be less respectful than students I taught elsewhere. There is, for instance, their palpable contempt for civilians. West Point cadets are accustomed to being taught by Army officers. During my first weeks at the academy there was a teacup tempest in the department about a cadet’s attempt to transfer out of a civilian professor’s class because the cadet wanted to be taught by an officer. I understood from conversations with colleagues that this attitude is not unusual, though few cadets express their preference openly. While I am not the only civilian professor in the English department, nor the only Aframerican, I am the only professor there this year who is both civilian and black—and I’m the only professor at West Point wearing dreadlocks. I have noticed cadets assess my status: “Ma’am, do you have a Ph.D.?”

I love my cadets, though, and am touched by their sense that poetry is important to them. There have been days when I’ve gone into class filled with near-despair at the apparent meaninglessness of what I’m doing; when I feel I can almost see through those uniformed young people to the officers they will become, and I wonder why in the world the commander of, for example, a battalion of tanks would need to know how to recognize a metrical substitution in an iambic pentameter line. On these days I’ve sometimes stopped my headlong recitation of information, or my enthusiastic demonstration of a given poem’s merits, to ask whether cadets really care about these things. Yes ma’am, they respond; they do care; they’re interested; they want to know. They are in the course, they say, because they want to learn as much about poetry as they can. One or two have gone so far as to list for me the names of soldier-poets in various cultures, wanting me to see the models they have inwardly set for themselves. Their regimen of academic, military, and physical training makes it very difficult for them to find the downtime necessary for the reading and writing of poetry. They cannot study poetry as they say they do other subjects, by the “spec and dump” method: cramming for exams, then forgetting most of the material immediately after the exam. When I am teaching it is not a body of information. It is goal-less, open-ended.

Mine is not the only poetry course available to West Point cadets. For the past ten years the plebe (freshman) year English course has focused on contemporary poetry. Each spring the entire plebe class has read books by four poets, who then appeared on campus to read their poems and to answer questions. This is the last year of this exciting experiment; next year’s plebe English course will more predictably focus on a martial theme. The poetry-focused plebe course tried to make cadets sensitive to the nuances of language. Their writing assignments asked them to distill a poem by selecting one small phrase from which to extrapolate a reading of the poem as a whole. While this approach has its rewards, it runs the risk of reducing the pleasure of poetry reading to a task, a search for the key word or phrase that will unlock the poem’s meaning. The method I am trying to teach requires time and quiet. And these are in short supply at West Point.

My cadets often ask how they compare to “normal” university students; whether I have modified my “normal” teaching to accommodate them. I haven’t been sure how to answer their question. I could say that, knowing how little discretionary time they are allowed in a day which begins at 5:30 and ends with taps at 11:30, I am more careful making their assignments than I am when making assignments to my “normal” students, much of whose time is their own. I know I’m less likely to be annoyed, and certainly less likely to express my annoyance, when they inform me that they will miss classes. Receiving e-mail messages in which I am addressed as “ma’am” and respectfully informed that a cadet has guard duty, or must be away for a “trip-section,” or a field trip, evokes a different emotional response from noticing that a student is missing from class, or has come to class unprepared, or is completing work for another class as I lecture. And, given the nature of human history, given unforeseen natural disasters, given our failure to learn from our mistakes, these young people are liable to be in a situation of turmoil or armed conflict someday. I teach them both more gently and more urgently than I do my other students.

We’ve been studying prosody, writing and reading poems. A few days ago, when one of the cadets exclaimed, “Wow! This is cool!” as I pointed out the fact that Frost’s poem, “Acquainted with the Night,” is a terza rima sonnet, everyone laughed, but then they agreed that knowing something about the sonnet enhances their enjoyment of one. I’m pretty certain that I can teach them enough about technique to enhance their appreciation of poetry. I’ve been delighted by the progress I’ve seen in the exercises they hand in or bring to my office. They are learning to use sophisticated tools: metrical substitution, slant rhyme, caesura, enjambment. I like to imagine them twenty years from now, Army officers who read poetry and write poems. Officers like my dad, whose briefing notebooks of acronym-studded militarese and doodles are punctuated by pages of his original sonnets.

Possibly more valuable than prosody or even poetry, however, is the contemplative practice I’m requiring of my students. I’ve been telling them that poetry is a slow art; that poetry readers must stop to savor words, phrases, sentences; that they can’t read a poem with the same minds that read novels or engineering texts. I’ve been arguing that meditation practice teaches skills essential to the enjoyment of poetry. Yet, though I really believe this, and have regularly listened to inner silence for many years, I am only a dabbler, a dilettante, a daydreamer, most of the time a backslider feeling slightly guilty about not meditating. But the Contemplative Practices Fellowship enabled me to work with several serious practitioners and students of meditation, from whom I’ve learned a great deal. One, a solitary priest who was a Benedictine monk for many years, said he thought meditation might offer something very important to West Point cadets, that it will teach them the gift of interiorization and humanization, and that learning to confront their vulnerabilities and weaknesses through trying to meditate will teach them compassion. He said the best leaders are compassionate, and that military history shows the worst leaders to have been more macho than compassionate. Meditation, he said, will teach them to see beyond surface appearance, to recognize what real strength is.

One of my high school classmates, who graduated from West Point in the class of 1968, also reassured me:

I spent almost twenty-five years in the Army and think I have a pretty good handle on the character traits and values that are both needed and present in the best leaders. We have a unique profession and it requires almost an oxymoronic type of individual to do it well. A good leader in times of stress, whether combat or peacetime, must not only know the men he leads but also himself. He must know his limits and theirs, when to push and when to back off. He must have compassion yet be ruthless in imposing and enforcing standards. He must be able to go days at a time without rest, demand it of others, yet find a way inside himself to relax whenever he can. Do we call that repose? If so, who else needs it more?

Armed with their advice, as well as that of several other friends, among them a poet who practices Zen, an Episcopal priest who holds a Yale Ph.D. in mysticism, and two other scholars of the mystical tradition, I planned a course we put on-line.

The plan has, of course, changed as I have worked with the cadets during the semester. As in any other course, the semester develops out of the interplay between the syllabus, the instructor, and the students. And, as in many of my courses, I have been plagued by self-doubt, never sure I’m teaching well, never sure the students are learning what I am trying to teach them. That self-doubt has, this semester, been exacerbated by the clash of our very different cultures. Sometimes I feel like an aborigine lecturer at Oxford. These ramrod kids in their gray uniforms, their shiny shoes, their “yes, ma’am”s and “no, ma’am”s? I’m teaching these people to meditate? Sometimes it feels absurd. Yet, when I’ve asked them whether they would like to abbreviate our communal meditation, or dispense with it altogether, the cadets have unanimously elected to maintain those five minutes of silence at the beginning of class. “Ma’am, those are the best minutes of my day,” they say. “I look forward to those five minutes, ma’am.” Several have suggested we meditate for more than five minutes. They turn off the lights, loosen their ties; some of them take off their shoes and sit cross-legged on the floor.

I set the timer. We close our eyes; we enter silence.

I’m having them practice several different techniques during the semester: We’ve done two weeks of breath-awareness meditation, two weeks of mantra meditation, two weeks of meditating on small pebbles, two of meditating on the gift of forgiveness, a walking meditation during Spring Leave, two weeks of awareness meditation, two of koan meditation, a final week of simple silence. In the last week of the semester we will lay out a labyrinth, inviting the entire Corps of Cadets into its meditative space. Sitting there in the dark room, surrounded by intelligent, strong, healthy, dedicated young people in uniform, I sometimes cheat, open my eyes, and look around. They sit with closed eyes: so young, so full of future.

I’ve asked them to keep meditation journals. Sometimes a cadet will ask for a minute or two of silence after our classroom meditation, so he or she can jot down a thought that occurred. They bring their journals to class; occasionally one will open his or her journal as we converse, and read to me a fragment of verse or an observation. They write of the trivial frustrations of meditation practice:

“I did 15 minutes right before I went to bed last night. Bad idea. I ended up falling asleep and slept until this morning.” “I quit tonight after 5 minutes. It was useless to even try b/c all I see are Fluids equations. I have a test tomorrow & I have a big fat F in the class.” One wrote a little poem:

Meditation

(with bubble gum in my mouth)

chomp

I forgot. Hard to focus on

smack

clearing my mind

chomp chomp.

Now the

BUBBLE

YUM

has lost its flavor.

no smack

So I wait until the

no chomp

alarm sounds.

Another cadet wrote:

Today’s meditation was so great for me, although perhaps it stepped away from the intentions of our meditations. There were so many thoughts in my head and angry, frustrated, stressed-out, mad, sad feelings inside I was having trouble with a focus and keeping my mind “blank” and open-minded. So, along with breath awareness, I felt my breath pull all of my negative emotions and feelings from the bottom of my feet to the top of my head and out with my exhale. Then, I followed that breath a little. I saw the clean air enter my mouth and travel through from the bottom to the top and through my lungs and back out all over again. I am disappointed in the way that I am explaining/describing this, but it really helped me relax and feel calm and refreshed and hopeful that things will get better or that a new day will come.

Later in the semester, as our practice slowly deepened, she wrote:

In class, we had to pick a couple of verbs from poems that we wrote and make sentences. Kevin made one that I loved: “Swim through a heartbeat of clouds.” Anyway, while I meditated, I thought about swimming through clouds. It was incredible. And over & over in my head, I said the sentence. I don’t know if that was meditation or not, but I got up and felt so wonderfully relaxed. It was like I had been swimming in clouds.

Another cadet wrote midway in the semester:

The Cry of the Seagull

I meditated today down by the river. I watched the ripples in the river and felt the wind in the trees.

I did not have much success counting my breaths and keeping my focus, but I felt relaxed afterwards. I was inspired by what I saw and felt. I have recently had trouble understanding the purpose behind human suffering and its relation to the Christian idea of God. However, I enjoyed stepping away, sitting down and focusing on my breathing. Oh yeah, I entitled this entry “The Cry of the Seagull” cause a seagull cried and shook me out of my meditation.

Another cadet wrote:

I have been wanting to focus more on the present than I have been; the predominant West Point attitude is to look a hundred years into the future, deciding everything short of which wallpaper you are going to put in your house. I need to remember, in this gray winter paradise, that we exist for today; if I were to die tonight, would I be pleased to know that the last thing I did was Engineering homework? I doubt it. So, I used “here, now” and it seemed to pretty much focus me on the present.

He later made up his own mantra: “Become the virtue of all that is true.”

Of the twenty-eight students, only two or three found the meditation practice unsatisfying, and those were the ones whose first few journal entries demonstrated a great deal of resistance to the very idea of meditation. Yet even these, while writing that meditation was doing nothing for them, often betrayed something else: “I noticed the way West Point smells today. It has a distinct odor to it all its own. I can’t actually identify what it smells like other than perhaps wet stone . . . but that doesn’t sound right because what does wet stone smell like, right? Unless, of course, you have smelled wet stone.” I am tempted to quote insights from each of the journals which I find deeply interesting:

Today a lot of things happened with me and the rock. It told me that imperfections are what make us interesting and beautiful; if we were all perfect and flawless, there would be no satisfaction in differences, no wonder, no awe. It also asked me to channel my negative energy into its cracks, much like we channel our energy into the cracks of other people’s souls. When we channel it into other people’s “cracks,” it usually ends up being offensive or confrontational; the rock has no feelings, so there is no need to worry about pissing it off.

Another:

I became preternaturally aware of the silence. Even the roar of the blood was silence, for I alone could hear it. And I think I hear something beyond the silence, the voices in my head which this meditation spiel is so interested in. They weren’t saying anything to me; they were babbling, murmuring amongst themselves. And they sounded happy. The silence in the air and in my head seemed like a clog in the toilet. Or a great big bite of peanut butter stuck in your throat. It was in the way. It obstructed reality. Poets are always so gloomy, but I think it’s only the dead silence that’s really dark and sorrowful. The unintelligible voices behind it sounded like songs; they sounded like green grassy hilltops in the sun.

Reading these meditation journals, I feel like a parent watching her child learn to ride a bike.

So here I am, a fat, old, dreadlocked blacklady poet, in a world in which everyone is young, everyone is jogging around, perpetually in training. A world in which students and faculty are told which uniform they must wear, and what they must teach and learn. An academic world in which many of the teachers have seen combat. A world in which cooperation and camaraderie are literally lifesaving values. A world in which people seriously, without irony, refer to the “art” of war. A world of individuals dedicated to serving our nation. Sometimes I have to pinch myself, remembering how I fell out of my patriotic dream in high school when we studied the history of the Panama Canal, remembering my participation in marches against the war in Vietnam, my regular donations to the Fellowship of Reconciliation. I grew up believing in this country, in its dream. Yet the older I grow, the firmer my conviction that the American Dream has devolved into the planet-eating nightmare of multinational corporations. Would I be willing to kill or to die for Microsoft?

So here I am, a fat, old, dreadlocked blacklady poet, in a world in which everyone is young, everyone is jogging around, perpetually in training. A world in which students and faculty are told which uniform they must wear, and what they must teach and learn. An academic world in which many of the teachers have seen combat. A world in which cooperation and camaraderie are literally lifesaving values. A world in which people seriously, without irony, refer to the “art” of war. A world of individuals dedicated to serving our nation. Sometimes I have to pinch myself, remembering how I fell out of my patriotic dream in high school when we studied the history of the Panama Canal, remembering my participation in marches against the war in Vietnam, my regular donations to the Fellowship of Reconciliation. I grew up believing in this country, in its dream. Yet the older I grow, the firmer my conviction that the American Dream has devolved into the planet-eating nightmare of multinational corporations. Would I be willing to kill or to die for Microsoft?

Yet I hold the conviction that peacekeeping is a noble calling. Of the twenty-eight cadets in my classes this semester, several have jumped from airplanes; two plan to fly helicopters. One wants to be an astronaut. But most of them say they’re not sure why they have stayed at West Point beyond the two-year point of no return. They are third- and fourth-year students, now, and are therefore committed to at least five years in the Army after graduation. Most of them say they don’t necessarily plan to have military careers; they are English majors; what they really want to do is read and write. Yet, apparently lacking the cynicism of my “normal” students, they seem more idealistic; ironically, more innocent. They are as willing to put themselves on the line in their poems as they are to try new meditative techniques. Some of them are writing pretty good sonnets, experimenting with slant-rhyme and split-rhyme. I read their poems delighting in the growing facility with which they are learning to use the tools, and respecting the emotional risks they are willing to take in order to speak their truths. I hope that by teaching these twenty-eight cadets how to find and hold interior quiet, I am giving them the wherewithal of wise conflict resolution. Perhaps poetry will help them to lead others toward peace. There are, after all, precedents: warrior-poets. The great general George S. Patton, a West Point graduate, though no Wilfed Owen, was nevertheless a serious amateur poet. In 1945, in a poem which described the moon looking down on a battlefield, he wrote:

The Moon and the Dead

Yet not with regret she mourned them,

Fair slain on the field of strife,

Fools only lament the hero

Who gives for faith his life.

She sighed for the lives extinguished,

She wept for the loves that grieve,

But she glowed with pride on seeing

That manhood still doth live.

The moon sailed on contented,

Above the heaps of slain,

For she saw that manhood liveth,

And honor breathes again.

Heroes, faith, pride, honor: values the majority of American culture has not believed in since The Lost Generation got lost. No one believes in those values anymore, we say, except right-wing religious fanatics and fools. But who distributes food in famine? Who delivers disaster relief? Who goes when we need to send someone into strife? Although it has not altered my congenital pacifism, working with West Point cadets has allowed me to see our military almost as I did when I was a child, proud of my father’s uniform. To see soldiers not as uniformed, muscle-bound G.I. Joe skinheads, but as volunteer firefighters willing to enter a heat-blinding inferno to rescue a terrified child still clutching the burnt match. I hope meditation will help my cadets recognize, even disobey, stupid and unjust orders, and to give wise and well-considered ones. I hope they will be soldiers who live the all-but-lost values of a nation conceived in the absurd concept of liberty and dedicated to the ridiculous proposition that we are all created equal. I hope they will be soldiers who live the humanist values kept alive by the poets, aborigines, and fools who refuse to close the door on our inner wilderness, with its echoing silence. We, after all, are crazy. We bring that verdant underworld jungle of absurd and necessary values into the marketplace, into the classroom, into this white man’s world, even—as crazy as it seems—into the citadel. ▼