Some artists actually look like their work. The libidinal Picasso, the playful Chagall, the austere O’Keeffe, R. Crumb. Meeting Ned Kahn, one might not guess that this artist conjures tornadoes or simulates Neptune’s storms. For more than twenty years, though, the soft-spoken Kahn—a longtime Buddhist practitioner—has created sculptures and installations that evoke the most tempestuous forces of nature. Whirlwinds and landslides, volcanoes and black holes, all rage through his northern California studio, while the artist himself occupies the still center.

Kahn, a youthful forty-four, has a narrow face and dark eyes that often focus in the distance. His look of amusement, which is not quite perpetual (but close to it), is centered on his mouth. A recent recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, Kahn recognized his life’s calling early on: His mother used to bring him to junkyards, where he collected the various objects that, at age ten, he assembled into his first “exhibition” of sculptures. From there his career progressed, as local interest in his work evolved into global fascination.

My own fascination with Kahn’s art began in the mid-1980s, when I saw his first Tornado at San Francisco’s Exploratorium. The twisting whirlwind of fog, eight feet tall, looked like a prop from The Wizard of Oz. I was filled with the childlike awe one experiences when something famously unapproachable is brought up close. It was like seeing sharks in an aquarium, or watching bands of lightning climb a Jacob’s Ladder. A few years later, during a residency at the Headlands Center for the Arts, in Marin County, California, the artist replaced the windows of an old Army barracks with hundreds of tiny hinged panels. As each passing breeze stirred the matrix, sunlight ebbed and flowed across the walls in rhythmic patterns: a self-portrait of the wind.

All of Kahn’s works provide insight into the ever-changing, interdependent world of natural phenomena. Some are deceptively simple: spinning glass globes that, filled with pearlescent liquids, mimic the turbulent atmospheres of the solar system’s gas giants; trellises of angled mirrors that reflect the tidewaters at the Point Reyes National Seashore. Others, inspired by the geologic forces that carve rivers and sculpt sand dunes, invite people to create their own miniature landscapes. And a very few are strictly passive—such as a unique observatory that encourages visitors to recline on comfortable lounge chairs, gaze through polarized portals, and view the passing clouds.

“I’ve always been attracted to the idea of making visible things that are invisible,” muses Kahn. “Somehow, that seems to be something of a Buddhist notion—although I suppose that all religions have some aspect of that: of the invisible being revealed.”

Kahn’s home is near Sebastopol, California, close to a winery where silver tinsel—a futile attempt to keep away birds—flutters from the vines. He lives with his wife, Jeanie, and their two children. A converted barn serves as his machine shop and office. We step past sheets of Plexiglas, painted metal cones, and jars full of glass microspheres (microscopic marbles that he uses to simulate dust or earth in some of his self-contained sculptures). A banjo hangs on the wall. The only icon of Kahn’s steadfast spiritual path is a small Japanese buddha, nearly hidden in an alcove above the stairs to his study.

Kahn was introduced to Zen by Ken Ring, a psychology professor at the University of Connecticut, in 1980. When Kahn moved to California he landed, seemingly by chance, in an apartment across the street from the San Francisco Zen Center.

He sat zazen for a couple of years—until well-known Vipassana teacher Jack Kornfield came to the center and gave a talk. “Vipassana seemed much more in sync with my sensibilities,” Kahn says. “Zen was too austere and severe for me. Vipassana was basically Zen, but without all the Japanese cultural and religious stuff along with it.”

At the same time as he was involved with the Zen Center, Kahn became an artist-in-residence at the Exploratorium. He worked there fifteen years, creating his first large-scale environmental sculptures and becoming the protégé to the museum’s founder, Dr. Frank Oppenheimer, a brilliant physicist who had worked with his brother, J. Robert Oppenheimer, on the Manhattan Project.

“In a dusty corner of the Exploratorium, there’s the sign Frank made when the place first opened in 1969,” Kahn reflects. “Spray-painted on plywood, it says: ‘Here Is Being Created The Exploratorium: A Community Museum Dedicated to Awareness.’ It struck me, when I started working there, in 1982, what an amazing thing that was: to use the word awareness as the foundation of your museum.”

It’s a real challenge to bring that quality into the world of contemporary art, which is typically about reaction. I ask Kahn how “awareness” figures into his work.

“Vipassana, and Zen, too, are very sensory,” he explains. “A lot of it is about being there with your seeing, hearing, feeling, smelling. So I try to create art that can be appreciated with the senses alone. You don’t have to figure it out. A lot of modern art is about figuring out how what you’re looking at connects to other streams of thought. I’m interested in creating art that makes visible, and brings to the level of attention, something that’s already occurring—things that frame natural phenomena, like clouds or wind or waterspouts, in ways that focus people’s awareness of the world around them.”

Inquiry is inherent in many contemplative traditions, from Advaita to Zen, and it’s a keystone of Kahn’s work. He sometimes refers to his artworks as “questions of nature.” It’s a phrase that scientists sometimes use to describe their experiments, but Kahn’s goals are different.

“Often scientists’ questions are very specific; they’re looking for an answer that they can quantify or reproduce, whereas I’m allowing a natural phenomenon or process to sculpt itself. I’m posing a question: What happens if I combine air and sand? Or sand and liquid? Or liquid and air? But I’m not looking for a mathematical answer, I’m looking for a visual one.”

Kahn meditates for an hour every morning and evening. “In the last twenty years,” he speculates, “I’ve probably not sat maybe four or five days. And those were really bad days, when I’ve cut myself on a machine or something. So it’s nonoptional. It’s actually dangerous for me not to meditate!”

The main obstacle to his practice, he admits, is stress: the professional obligation to stand in front of a board of directors, or an art commission, and submit a very personal (and sometimes half-baked) concept for review. Wrestling with hope and fear, he says, takes a big psychological toll.

“And there’s also the fact that the kind of work I do, by its inherent nature, is slightly out of my control. The artwork is often a collaboration with nature, which may or may not cooperate. So I’m presenting an idea that I’ve more or less convinced myself is going to work. But I’m not one hundred percent convinced—and this roomful of people is zero percent convinced!”

Last October, Kahn became a MacArthur fellow. I ask if the award, with its high-visibility badge of “genius,” is at all a distraction, drawing more ego into his work.

“No,” he says, laughing. “My wife makes sure I have as little ego as necessary! But the MacArthur thing is interesting,” he allows, “because I’ve noticed that people are taking my half-baked ideas more seriously. And it makes me a little nervous—because a lot of my ideas are bad. It’s much easier to generate ideas,” he says wryly, “than to come up with something that really works.”

At present, Kahn is working on some fourteen projects—from small exhibits for a hands-on science museum to a complete redesign of the San Diego waterfront. Other commissions have included “alien” landscapes for New York’s Rose Center for Earth and Space, a seven-story tornado for a German exposition, and a seaside fountain powered by the energy of crashing waves.

“If you were asked to create an installation for a meditation retreat center, or for an Asian art museum,” I ask, “what might you propose?”

“I’d do one of the flowing wind pieces,” he replies without hesitation.

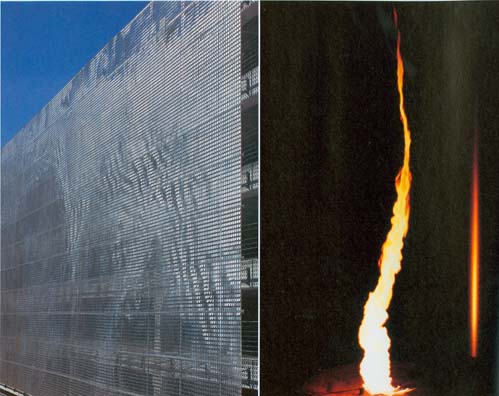

It’s an appropriate choice. Kahn’s wind sculptures—which range in size from window-size panels to huge murals that cover entire buildings—are probably his most evocative, and contemplative works. They’re composed of hundreds, or thousands, of tiny aluminum squares, each with a hinge on one side. As the wind gusts by, the squares mirror the waves and patterns that move, usually unseen, through the atmosphere.

One compelling aspect of Kahn’s work is that it challenges our notions of duality and provides incontrovertible evidence of interdependency. “A lot of my artworks look at the boundaries between things—wind and water, fog and wind, water and sand—and the incredibly complicated things that happen within those boundaries.”

Kahn had a revelation during his Exploratorium days, while trying to get his first Tornado to work properly. After a year of trial and error, the work-in-progress was still finicky and unpredictable.

“Sometimes I’d be there late at night, and I’d re-aim the fans and the fog machine, and get it all fine tuned, and the thing would be working great, and I’d be so excited. ‘I finally got it! I have it all figured out!’ Then I’d come in the next morning and it wouldn’t work at all. I was going crazy. Finally, after months of this, I realized that it was all about the air currents in that big, old, drafty building. Which doors were open far across the museum, or where the sun was hitting outside, affected everything.

“It dawned on me how intertwined the sculpture was with the whole air system of the building. Where did the sculpture begin and where did it end? If it was being affected by the air currents in the building, which were being affected by the wind outside, there was never a real delineation between the sculpture and the atmosphere of the Earth. I’m fascinated with that whole notion—of sculptures with very blurry boundaries. It’s something you don’t often see in a traditional sculpture, like a bronze or a stone, with its seemingly crisp edge between the art and the environment.

“It’s the same with the flowing wind pieces,” he says. “The artwork is so entwined with its environment that, in a way, it is environment. It’s sculpted by winds that might have been generated by storms or ocean currents ten thousand miles away—so the whole atmosphere is linked to the artwork.”

Zen Buddhism traces its origins to the famous story of the sermon on Vulture Peak, where the Buddha sat in silence and held up a flower, turning it by the stem. One disciple—Kashyapa—was instantly enlightened. This “direct transmission” relied, like Kahn’s work, on pure sensory mojo; there was little if any cerebral work involved.

Though Kahn has moved away from Japanese meditation techniques, a koanlike simplicity still defines his art. His sculptures may say very little, but they embody Zen’s most basic tenet: total engagement in the present moment. There’s no magic involved; the artist’s daring or novelty are not the point. We’re simply brought back to the fleeting instant of now and its ever-changing dynamic.

“Jack Kornfield gave one particular teaching that has always stayed with me,” Kahn recalls. “He said that a lot of people are drawn to meditate because they think that they’re going to achieve magical states of mind, or see amazing visions. He explained that even after sitting for years, most people never have those experiences. Often, though, it’s the mundane, everyday stuff that becomes amazing. ‘Think about it,’ Jack said. ‘We’re living on this sphere of rock that’s floating in space. Somehow life evolved, and now we’re these bizarre animals that eat and change chemical stuff into energy. Now, that’s miraculous. What more do you want?’

“Almost all the artwork I’ve done has been in that direction,” says Kahn. “Trying to remind people just how strange and mysterious the physical world really is.”