On a sparsely populated mountain five hours northeast of Vancouver by car, lies a cutting-edge, off-the-grid monastery that is a paragon of green dharma. Sitavana Monastery gets 90 percent of its power from solar panels and relies on only 10 percent of the energy per person used by the average Canadian. Yet, its 12 kilowatt solar array supports an often-busy monastery complex that includes nine kutis (small huts), storage buildings, and main building equipped with lodgings, a library and meeting spaces, a kitchen, and a spacious and bright meditation hall. Establishing Sitavana (Pali for “cool forest grove”) as both a thriving wilderness refuge for practitioners in the Thai Forest tradition of Theravada Buddhism and as a role model of ecological mindfulness is an expression of the lifelong preoccupations of its abbot, Ajahn Sona.

“I’m a nature mystic,” Sona told me with a twinkle in his eye, “I can’t get enough of it. The Buddha said, ‘Monks, practice in the forest,’ that was very deliberate advice.” But in the beginning, the monastery’s creation and subsequent success were far from guaranteed.

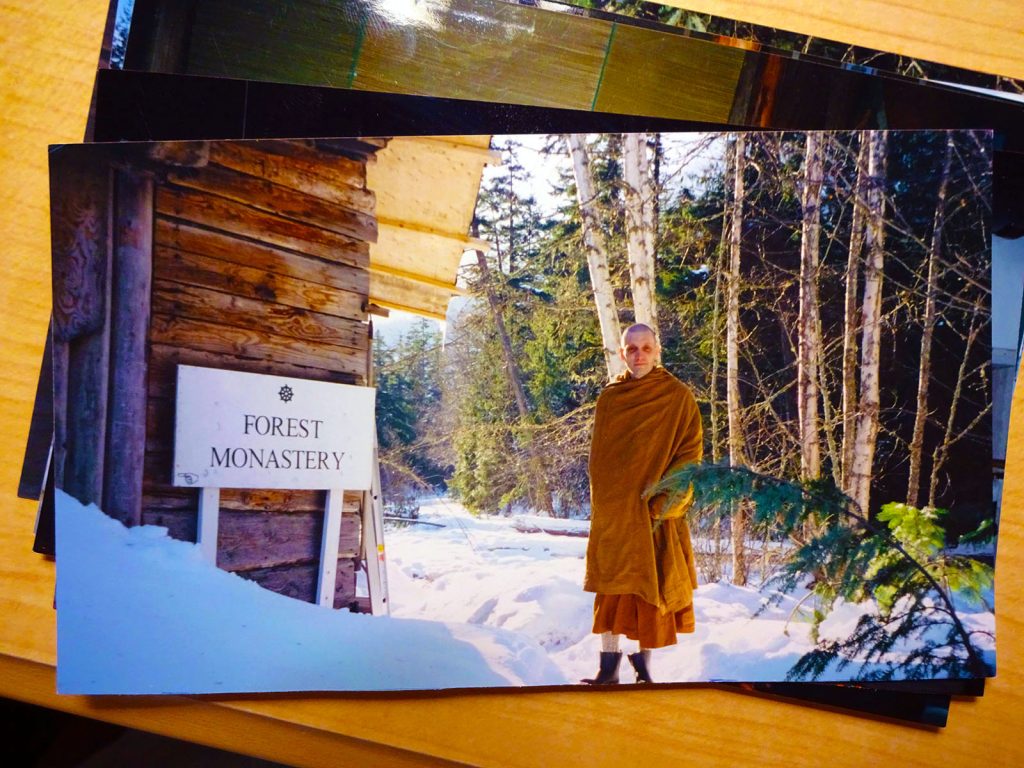

In 1994, Sona returned to his native Canada from studying at Wat Pah Nanachat in Thailand—a monastery set up by the Thai master Ajahn Chah—at the invitation of the Sri Lankan Buddhist community. He was joined by his fellow orange-robed Wat Pah Nanachat disciple Ajahn Piyadhammo of Germany, and together they struggled to maintain their monastic lifestyle near the isolated mountain village of Pemberton, British Columbia. Monks in the Thai Forest tradition do not handle money, engage in agriculture, store or cook food, or eat after midday. The vinaya, or monastic code, forces monks to depend on laypeople for supplies and to eat only the food that is offered to them each morning. This way of life is part of what Ajahn Thanissaro Bhikkhu calls “an economy of gifts,” where laypeople give monastics what they need to practice and monastics give laypeople the guidance, inspiration, and wisdom that is enabled by their life of meditation. The problem that Sona and Piyadhammo faced, however, was how to establish this economy in a society that doesn’t understand it and in a location far from any marketplace.

“We lived on a shoestring in Pemberton,” Sona told me. “We had a steward who stayed with us to help out. If he needed to buy groceries he had to hitch-hike into town 25 km [15 miles] away since we had no vehicle. People brought us bags of rice and so forth, but we had no refrigerator and had to keep things cool by submerging it in a river that went by near the door. Sometimes a bear would take off the food or it would be washed away and we’d have nothing for a few days. Let’s put it this way,” says Sona with a laugh, “the shack was overpriced at $50 a month.”

While living in Pemberton was tough, in some ways it was a good fit. The area resembles the isolated and often treacherous terrain where they practiced in Southeast Asia, and they didn’t have the money to live anywhere else. And it was while living on the outskirts of Pemberton years prior that Sona was first encouraged to ordain as a bhikkhu [monk]. Out where the highway dead-ends in Indigenous territory, Sona had rented a shack with no water or electricity after walking away from his career as a classical guitarist in Ontario. By then, Sona had already spent some years studying Korean Son and Tibetan Buddhism and had moved to Pemberton to live as a meditating hermit and reconnect with nature. Sona has been concerned with defending the ecology since his college years, when he wrote articles on pollution and the preservation of threatened places as an amateur journalist and would escape to go camping even during Ontario’s freezing winters.

Related: The Buddhist Traveler in Vancouver

“The lush forests of BC seemed like a good place to do this impossible thing, to find a shack in the middle of nowhere,” he told me, explaining that he had hoped to combine his love of nature and his newfound interest in deep meditation. “The first year I knew I could do it,” Sona says. “The second year I knew I wanted to do it. The third I knew I would never do anything else.”

One of his only neighbors in Pemberton, a Sri Lankan hermit he occasionally crossed paths with, Kirti Senaratne (who would later become a dedicated supporter of Sitavana), would later convince Sona to try out becoming a bhikkhu in the Theravada tradition. Sona then left to train as a bhikkhu at the Bhavana Society in West Virginia with Bhante Henepola Gunaratana (of Mindfulness In Plain English fame) before moving to Wat Pah Nanachat.

Upon returning to Canada, Sona was prepared to handle the simplicity and privation of Pemberton. After Piyadhammo eventually left for Burma to study with Pa Auk Sayadaw, Sona told his growing community of lay supporters it was time to get a real monastery.

In 1997, Ajahn Son and his supporters identified an affordable plot of land in the Birkenhead Valley, where he established Birken Forest Monastery—in the heart of British Columbia’s Bible Belt. Relations with their neighbors were initially strained, but gradually improved thanks to what Ferguson calls Ajahn Sona’s “skill at disarming people,” a marked feature of his personality. Not everyone was impressed, however. After Sona’s kuti (monastic hut) was built high up on the hillside, a former Catholic monk who lived across the valley affixed a giant crucifix to an adjoining property, high up on the mountain where it would look down—and confront—the new Buddhists.

Along the way Sister Mon, a Thai maechi (monastic) with a background in engaged Buddhism and links to Thich Nhat Hanh’s Plum Village, joined Ajahn Sona. Since then, they have remained as the sole fixtures while other monastics have visited, trained, and left for other adventures or disrobed and rejoined lay life.

In 2001, as lay support and donors grew, it became possible to dream bigger, and Birken relocated to Kamloops (about 270 km to the east) and took the name Sitavana. Ajahn Sona recounted during a TEDx talk finding a giant building in what seemed like the middle of nowhere. When they asked how it got there, the realtor said the previous owner “had been a dreamer.” Later they found out it had been a marijuana grow-operation. “Almost every monastery I know of in North America has taken over for a grow-op,” said Ajahn Sona. “We have two things in common: out of sight and out of sound.”

The monastery Sona built married his two passions: traditional Buddhist monasticism and ahead-of-its-time ecodharma. Sona sees all of this as an opportunity for laypeople to have an authentic experience of Dharma practice that is both in a natural setting and responsible to the place it lives in.

“People want to be in nature, but they don’t know how to be there . . . they might drink and play cards, they don’t have the support for having the simple experience of nature,” Sona said. “This is a retreat monastery. When people come here they’re immersed. We’re in the middle of nowhere. The nearest neighbor is 10 km [~6 miles] away. It’s nothing but nature here, but it’s a supported situation. We have sittings, meals shared together, they can have interviews with me, we have tea-time together, but they can wander around in nature as much as they want. A lot of meditation retreats now schedule every moment, but we don’t do that. This is more like it was at the time of the Buddha.”

Having built a life which will allow him to tread very softly on the earth, Ajahn Sona now has become a teacher of ecodharma as well. He said in a TEDx talk in the Okanagan, “Is [it] a good idea to try to purify the environment while experiencing despair, anxiety, and fear?” Comparing our bodies and minds to ecologies that need protection, Sona added, “There are alternate fuels to get things done and they have a lot of power to them. Such things as patience, generosity, kindness, and clarity get things done. Anger and all of the things that can sometimes go with the environmental movement get things done as well—but they have a toxic side effect.”

It is hard to imagine who else but Sona could have pulled off the creation of Sitavana. Remarkably, Sona has not just created an ecologically sound hermitage in the pristine Canadian wilderness for himself, but has managed to create a community which offers that to anyone who wants it, both as a refuge and as an example.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.