While Zen monks did live in caves in part to find refuge from the elements, there’s more to the story than just avoiding thunderstorms—they were also hiding out from the government. Ancient Chinese kings were loath to let too many “home-leavers” skip out on paying taxes, serving in the army, growing food, or having children—the activities needed for a country to survive and for kings to live in style. The king viewed monks who claimed exemption from these activities just because they wanted to practice meditation as deadbeats or brigands. Monks who were caught were defrocked or worse.

So genuine Buddhist monks who wanted to leave the world could find no better place to do so than in a cave on a mountain somewhere where no king could find them. It was a home-leaver’s perfect home away from home, offering shelter in cold winters, concealment from the king, and a quiet place to meditate. But, of course, caves had certain drawbacks: they might be too far from water, for instance, or too far from believers who could offer dana for support.

In this context, the ancient caves of Western China’s Dunhuang are particularly fascinating. There, meditating monks found natural caves situated near the treasure-laden caravans that traveled the Silk Road. Merchants coming from the Middle East and Europe, eager to get their goods safely to and from China, undoubtedly paid a handsome contribution for lucky blessings or protective charms that would defend them and their treasures against the next sandstorm.

This happy symbiosis between monks and merchants made Dunhuang a vital center of Buddhist activity, a key stop on the path where Buddhism entered China from southern Asia. In Dunhuang, monks in good circumstances had the time and energy to translate newly arriving Mahayana scriptures. Centuries before Buddhism flourished in Tibet or Zen took root in Japan, Dunhuang was the wellhead for Buddhism’s entry into Asia.

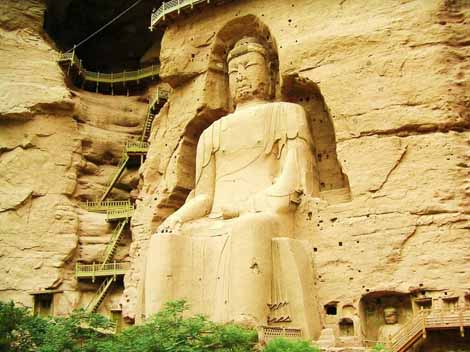

The kings of that time saw what was happening in Dunhuang and wanted to control this important activity. So the Northern Liang Dynasty emperor took over the caves and carved new statues of Maitreya Buddha inside of them—in the likeness of his own face! He wanted lay followers to equate the spiritual authority of Dunhuang with the king himself.

In any case, this icon-making activity continued for centuries, until Dunhuang became a staggeringly vast complex of caves filled with magnificent Buddhist icons, art, and translated scriptures. Then countless lay devotees and tourists came to pray and gawk, and the Zen monks had to go elsewhere if they wanted to meditate in peace.

This post is the first of author and scholar Andy Ferguson in our new “Consider the Source” series. As an old Chinese saying goes, “When drinking water, consider the source.” In the coming weeks, Ferguson will ask and answer seemingly simple (but in the end, profound) questions about the “source” of East Asian Buddhism, weaving a tale of both spiritual inspiration and political intrigue.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.