Buddhist practice and Buddhist art have been inseparable in the Himalayas ever since Buddhism arrived to the region in the eighth century. But for the casual observer it can be difficult to make sense of the complex iconography. Not to worry—Himalayan art scholar Jeff Watt is here to help. In this “Himalayan Buddhist Art 101” series, Jeff is making sense of this rich artistic tradition by presenting weekly images from the Himalayan Art Resources archives and explaining their roles in the Buddhist tradition.

Himalayan Buddhist Art 101: Three Stories in One

Sometimes when you look at a painting, it can be taken at face value, and little more will be known about it other than the iconography. At other times, however, there are many layered stories to the piece of art, including the iconographic biography, the political environment in which it was made, its donor information, and even the actual creation of the artwork.

The painting shown here is of the Tibetan Buddhist protector deity Shri Devi Magzor Gyalmo. Shri Devi is the large centrally located wrathful figure riding atop a beige mule. She has six attendant figures at the right and left sides and one below. Four of the retinue figures are riding animal mounts and the two attendants have animal heads. In addition to Shri Devi, at the lower center of the composition is the Tibetan mountain goddess Tseringma, white in color and riding a snow lion, accompanied by her four sisters. This first story is the description of the iconography and the identification of the deity and accompanying figures.

The second story is very different from the first; it concerns prominent teachers and politics of 17th century Tibet. At the top of the painting are five figures. In the center is Drubkhang Rinchen, an important teacher of the 17th century. On the viewers left side are the two figures of Kardo Rinchen and Ponlob Puntsog Gyatso. On the viewer’s right side are the 5th Dalai Lama and the 2nd Panchen Lama. The interesting story here is the personalities and rivalries of these five characters.

Kardo Rinchen and Ponlob Puntsog Gyatso did not agree nor go along with the new concept being promoted in Lhasa in the 17th century that the Dalai Lamas, as a line of incarnation, were the emanations of Avalokiteshvara. The two scholars even wrote textual refutations against this new “controversial cult.” After a number of written exchanges, the writings of Kardo Rinchen and Ponlob Puntsog Gyatso. were banned in Tibet. It is very rare, then, to find this particular grouping of 17th century teachers in artwork from the time.

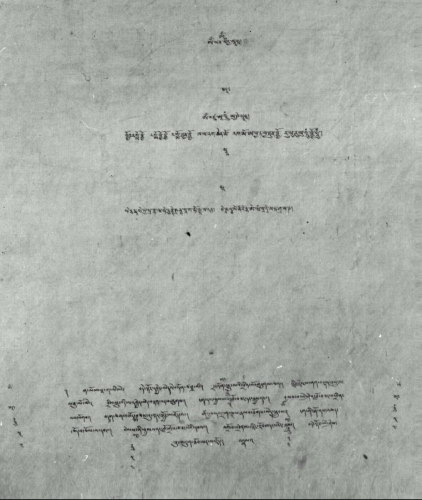

The third story relates to the physical creation of the painting. Fortunately there is a written inscription on the back of the composition recording the four donors of the painting. The first two names—and the two most recognizable of the four—are of Purbu Chog, a prominent teacher of the Lamrim System in the 18th century, and Lobzang Dargye, the 49th Ganden throne holder. After some detective work, the inscription on the back of the painting has also been found recorded word for word in the Collected Writings of Purbu Chog. He further states that the painting of Shri Devi belongs to a seven painting set. Two other compositions from the same set have been located, but the whereabouts of the remaining four paintings are unknown.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.