Meditation Schools of East Asia: Chan, Thien, Seon, and Zen

When people think of “Zen,” they often picture Japanese gardens, monastics in black robes, or some other image of quiet simplicity. But Zen is only one branch of a much larger family of practices. Born in China as Chan and carried to Vietnam, Korea, and Japan, the meditation schools built their identity on a bold claim: Practice is realization itself. They put meditation at the center of Buddhist practice and transmitted insight through teacher-student lineages. Over their long history, these traditions created distinctive texts, stories, arts, and communities. This page traces their origins, defining debates, and ongoing influence around the world.

Table of contents

- What Are the Meditation Schools?

- Origin and Development of Chan in China

- Lineages and Transmission: The Five Houses

- Core Debates and Practices

- Thien in Vietnam

- Seon in Korea

- Zen in Japan

- Foundational Texts and Records

- Women in the Meditation Schools

- Aesthetics and the Arts

- Meditation Schools in the Modern World

What Are the Meditation Schools?

The meditation schools of East Asia form a close-knit family of Mahayana Buddhist lineages that emphasize sitting meditation. The term “meditation school” (Ch.: Chanzong; Kr. Seonjong; Jp.: Zenshu) appeared in the 6th to 7th century in China to distinguish small groups of elite monks devoted to meditation (Ch.: chan) and linked to specific teacher lineages. This tradition developed in China as Chan, drawing on Indian and Central Asian teachings, and later took root in Vietnam as Thien, in Korea as Seon, and in Japan as Zen. These traditions each have a distinct history and style, but they share a concern with direct experience, teacher-student transmission, and the embodiment of awakening in everyday life.

Seated meditation (Ch.: zuochan; Jp.: zazen; Kr.: jwaseon) is the primary discipline. Monastics train through extended periods of sitting, direct guidance from a teacher, and the gradual cultivation of insight. The teacher-student relationship is anchored in lineage, a formal transmission that connects each generation to the founders of the tradition, tracing back to the Buddha. Although scholars question the historical accuracy of such lineages, these unbroken chains of transmission are treated as the lifeblood of the schools and help define their identity.

Historically, meditation-focused lineages were distinguished from the “study schools” that specialized in scriptural and doctrinal analysis. In some cases, this led to institutional separation. For example, monasteries in the Korean Seon tradition would specialize in one or the other, developing specialized training systems. Over time, many teachers attempted to reconcile the divide between meditation and doctrinal study, integrating them into a holistic practice that emphasized their mutual dependence. However, the distinction remained a defining feature of how these schools evolved.

In the 20th century, one branch—Zen—became especially popular outside Asia. Teachers and writers from Japan introduced the practice to Europe and the Americas, and the word “Zen” entered the vernacular language and pop culture. In this new context, the term was often detached from its Buddhist origins, used to suggest simplicity, calm, or aesthetic restraint. But Japanese Zen represents only one branch of a family tree of histories, practices, and cultural expressions; terms like “Chinese Zen” are more accurately expressed as “Chinese Chan.” The diversity of meditation schools cannot be reduced to a single tradition.

Despite regional differences, these Mahayana traditions are intimately related and share a common conviction: Awakening comes through direct experience, not doctrine alone. Practitioners should realize the Buddha’s message of awakening in thought, speech, and action. The path is lived in the immediacy of practice, under the guidance of those who have already walked it.

Origin and Development of Chan in China

Chan Buddhism emerged in China during the Tang dynasty (618–907), a prosperous time marked by significant cultural, intellectual, and political developments. Its origins lie in the transmission of meditation teachings and practices from India. The word chan is a transliteration of the Sanskrit dhyana, meaning meditative absorption. Early Chan developed within a Mahayana Buddhist landscape shaped by the translation of new Indian and Central Asian texts, as well as the influence of other Buddhist schools, such as the esoteric Tiantai and the scholastic Huayan tradition.

Legend credits an Indian monk named Bodhidharma (ca. 5th–6th century) with transmitting a direct, practice-oriented approach to China. The details of his life are uncertain, but he came to represent the ideal teacher who pointed beyond words and scriptures to the mind’s original nature. His successors, often referred to as patriarchs, were said to transmit the dharma from one generation to the next in an unbroken succession. By the time of the Sixth Patriarch Huineng (638–713), Chan had established itself as a distinct movement within Chinese Buddhism.

During the Tang dynasty, the Chan school enjoyed the patronage of the royal and aristocratic classes, experiencing significant growth and expansion. Monasteries were built and lavished with fine materials, along with offerings of food and supplies. Teachers like Mazu Daoyi (709–788) and Baizhang Huihai (720–814) developed new training styles, which included hitting, shouted exchanges, and strict monastic codes. This period saw the rise of the so-called Northern and Southern schools, each promoting different views on whether awakening was a gradual or sudden process. Though historians later exaggerated the significance of these debates, they nevertheless shaped the way later generations understood the diversity within Chan.

By the Song dynasty (960–1279), Chan had matured into an intellectual, political, and religious force. It had also absorbed elements of Pure Land devotion, ritual, and scholarship, while keeping meditation as its foundation. Monasteries became powerful centers of training and cultural production, preserving teachings and exchanges between masters in collections that continue to influence Chan practice. The Song dynasty was also the era of the “Five Houses” of Chan—lineages that would later spread to Vietnam, Korea, and Japan.

From the earliest years, Chan combined rigorous discipline with a flexible, responsive spirit. It adapted to ever-changing and diverse Chinese cultures without losing its meditative core, while also shaping culture in lasting ways. The teachings, training styles, and lineages that emerged during the Tang and Song dynasties would guide its development as it spread across East Asia.

Lineages and Transmission: The Five Houses

By the late Tang and early Song dynasties, Chan had developed into several lineages. These are known as the “Five Houses” of Chan—Guiyang, Caodong, Linji, Yunmen, and Fayan—each named after a founding master or the place associated with their teaching. Each lineage cultivated unique styles and methods but remained united by the centrality of meditation and teacher-to-student transmission.

The Guiyang, the first of the Five Houses of Chan, blended literary and esoteric expressions with subtle teachings. The Caodong school, later transmitted to Japan as Soto Zen, valued silent illumination (Ch.: mozhao chan; Jp.: shikantaza), a form of meditation that emphasizes stillness and clarity. The Linji, known in Japan as Rinzai, gained fame for its dramatic style, employing sharp words, paradoxical statements, or sudden actions to break through conceptual thinking. The Yunmen utilized brief, penetrating utterances that could overturn understanding in a single phrase; this elite school is credited with producing the Blue Cliff Record. The Fayan school stressed harmonizing with the conditions of everyday life. The Guiyang, Fayan, and Yunmen were eventually absorbed into the Linji school, which became the dominant Chan school in China.

The concept of “Five Houses” was a later systematization of the teachings, but it reflects the diversity within Chan Buddhism. Teachers trained in one lineage might incorporate methods from others, and many students moved between communities, receiving multiple transmissions. Some lineages eventually disappeared or merged, but their influence continued through texts, teaching styles, and monastic rules.

Lineage was central to Chan identity. Teachers traced and recorded their authority to the legendary patriarchs, using “mind-to-mind transmission” as a mark of authenticity. Modern scholarship has demonstrated that many lineage records were constructed after the fact, shaped to reinforce a particular community’s authority and control over monasteries and resources. Transmission signified that a student had directly realized the same awakening as the teacher, authorizing them to teach and eventually take their place; thus, much was at stake. Lineage was the glue that often held communities together, even during internal conflict.

When Chan spread, these transmission lineages shaped the Buddhist schools that developed in Vietnam, Korea, and Japan. Caodong and Linji inspired Korean traditions; Caodong influenced the Japanese Soto schools; and Linji impacted Japanese Rinzai. The teachings of Yunmen and Fayan left traces in Vietnamese Thien. Even today, teachers identify with one of the original Chan houses, transmitting centuries-old origin stories.

Core Debates and Practices

Chan developed in response to fundamental questions about practice and doctrinal understanding. A prime example is the pace of awakening: Did realization come all at once or unfold gradually through practice? Proponents of sudden awakening, such as the community around the Sixth Patriarch Huineng, emphasized that the mind is inherently pure and clear, and that awakening is an immediate recognition of this fact. Enlightenment happens in a limitless flash of awareness. Others argued that awakening comes only through gradual cultivation, and sustained effort is needed to clear habitual patterns and deepen awareness.

Variations of these two positions were debated and sometimes led to bitter disputes. While often framed as opposing views, some traditions combined them. One Korean Seon tradition, traced back to Jinul, the founder of the Jogye order, described sudden awakening followed by gradual cultivation: With sudden enlightenment comes the need to continue practicing and remove remaining karmic obstacles.

Another recurring question centered on the balance between meditation and doctrinal study. Although Chan is best known for its experiential approach, many Buddhist communities in East Asia studied scripture, particularly texts such as the Prajnaparamita Sutra, the Lotus Sutra, and the Platform Sutra. Some monasteries specialized in meditation, while others incorporated significant scholastic study. The distinction between the “meditation schools” and “study schools” became a recognizable feature of East Asian Buddhism, even when the lines were not always clear.

One of the most distinctive Chan practices is the use of gong’an (public cases)—encounters, questions, or sayings from early masters that are often puzzling or paradoxical. In Korea, the term hwadu (“word head”) refers to the central phrase from a gong’an that becomes the focus of inquiry. In Japan, the word koan describes both the case itself and the method of working with it. Gong’ans are tools to disrupt habitual thinking and facilitate a direct experience of reality, not necessarily riddles to be solved. Teachers present a student with a case and then test their responses in private interviews, using the exchange to gauge insight. Some modern Buddhist masters have challenged the continued usefulness of this method, since after many generations, the questions and responses have become somewhat familiar and rote.

Such debates and practices gave Chan its characteristic style: long hours of meditation, personal guidance from a teacher, and the challenge of cutting through conceptual thought. Styles varied among lineages and regions, but the aim remained the same—direct, experiential realization of one’s true nature and the integration of that realization into everyday life.

Thien in Vietnam

Meditation teachings entered Vietnam from China as early as the 6th century, where they became known as Thien. According to later histories, such as the Thien uyen tap anh (“Outstanding Figures in the Thien Garden”), the first lineage was introduced by Vinitaruci (?–594), an Indian monk said to have studied in China with the third Chan patriarch, Sengcan (?–606), before traveling south. He settled at Phap Van monastery and passed his teaching to Phap Hien (?–d. 626). Other claimed lineages include the Vo Ngon Thong (Ch.: Wu Yantong, ca. 759–826) line, linked to Baizhang Huaihai (720-814), and the Thao Duong line, associated with the Yunmen tradition in China. While these genealogies are now seen as retrospective constructions, they show how Vietnamese Buddhists framed their transmission of Chan and positioned themselves within the broader tradition.

By the 13th century, Thien took on a more distinctly Vietnamese form in the Truc Lam school. Founded by King Tran Nhan Tong (1258–1308) after he abdicated the throne to become a monk, Truc Lam blended Chan-style meditation with Pure Land devotion, Confucian ethics, and civic responsibility. It emphasized awakening in daily life, rather than in the meditation hall alone, reflecting Vietnam’s tradition of integrating religious and social concerns.

Unlike in China, Korea, or Japan, the Thien school in Vietnam never developed as a separate monastic institution. Instead, it functioned as a current within Vietnamese Buddhism, coexisting with Pure Land, scholastic study, and later Theravada communities. Temples often offered both meditative and devotional practices, and lay participation was central to sustaining the tradition.

The colonial era and the Vietnam War disrupted Buddhist institutions, but reformers sought to modernize and revive meditation. In the 20th century, Thien became central in movements for lay education and social engagement. Thich Nhat Hanh (1926–2022) drew on these currents to shape his vision of Engaged Buddhism, combining traditional practice with peace activism and humanistic values. His Plum Village community in France has since become one of the most influential Buddhist centers in the West, offering meditation to a global audience.

Today, Thien continues to shape Vietnamese Buddhism both at home and abroad. While less a tightly defined school than a strand of practice, it remains a tradition that integrates meditation, devotion, and ethical action into a distinctly Vietnamese path.

Seon in Korea

Buddhism entered the Korean peninsula by the 4th century, and Chan teachings arrived several centuries later. By the late 9th century, Seon tradition evolved into what became known as the nine mountain schools—monastic communities founded by monks who had trained in China and returned to Korea. The Chinese Linji lineages and, to a lesser extent, the Caodong helped shape early Seon schools as Korean monks adapted their teachings to Korean Buddhist culture.

Seon coexisted with other forms of Korean Buddhism, particularly the highly scholastic Hwaeom (Ch.: Huayan) school that focused on the influential Mahayana teachings of the Avatamsaka Sutra (Flower Ornament Sutra). Monks often trained in both approaches, combining meditative discipline with doctrinal study, which became a hallmark of Seon practice. Another key feature of Seon is the practice of hwadu—a focused question or phrase drawn from a gong’an, used to pierce through discursive thought. This method, germinating in the Chinese Linji tradition, became a defining characteristic of modern Korean Seon.

The 12th-century master Jinul (1158–1210) became one of Seon’s most influential figures, advocating a sudden awakening–gradual cultivation practice model and reestablishing the Songgwan-sa monastery as a center for disciplined practice and study. His writings and reforms helped unify the Nine Mountains into the Jogye Order (credited to Jinul’s disciple, T’aego), which remains the largest Buddhist school in Korea today.

Later centuries saw periods of decline, revival, and reform. During the Confucian Joseon dynasty (1392–1897), bureaucrats stripped Buddhism of its royal coffers, leading to the decline of many monasteries and temples. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, teachers such as the Seventy-Fifth Patriarch of Korean Seon, Gyeongheo (1846–1912), revitalized monastic life.

The Japanese occupation of Korea (1910–1945) brought significant disruption. Colonial authorities reorganized temple administration according to Japanese models, and some elements of Japanese Zen practice entered Seon monasteries. After liberation, reform movements sought to restore monastic discipline and adapt training for contemporary needs. These reforms created tensions that still exist in Korean Buddhism.

In the late 20th century, figures such as Kusan (1909–1983) and Seung Sahn (1927–2004) introduced Seon to an international audience, establishing teaching centers and lay-oriented dharma groups in the United States, Europe, and beyond. Today, Seon is practiced by both monastics and laypeople, with many urban temples and retreat centers offering residential training as well as programs for those living outside the monastery.

While deeply embedded in its Korean heritage, Seon continues to evolve, carrying forward its emphasis on direct experience and the interplay of meditation and study.

Zen in Japan

Chan (Jp.: Zen) reached Japan as early as the 9th century through Saicho (767–822), the founder of the Tendai school. During his studies in China, he received instruction in Chan meditation, but these practices remained within a broader scholastic framework and did not develop into a separate lineage. It was only in the late 12th century that monks such as Myoan Eisai (1141–1215), who introduced the Linji lineage as Rinzai, and Dogen Zenji (1200–1253), who returned from China to establish the Soto school, founded independent Zen schools. A third lineage, Obaku, arrived later in the 17th century through the Chinese monk Yinyuan Longqi (Jap.: Ingen Ryuki, 1592–1673). These schools defined Japanese Zen as a distinct expression of the Chan tradition.

Each lineage developed a characteristic style while also maintaining some similarities. Rinzai emphasized strict training and koan study to cultivate insight. Soto centered on zazen (Jp. for “seated meditation”) as “just sitting” (shikantaza), where meditation itself embodied awakening. Obaku retained strong Chinese influences, including chanting practices and monastic regulations. While distinct, the three schools shared a focus on discipline, transmission, and the authority of the monastery as a site of training.

Over time, Zen became increasingly embedded in mainstream Japanese culture. By the 14th and 15th centuries, its monasteries were centers of meditation, education, art, and ritual. It influenced calligraphy, ink painting, gardening, poetry, and even martial disciplines, and became a significant force in shaping Japanese culture and identity.

The modern period brought both crises and change. During the Meiji era (1868–1912), state reforms dismantled the old temple system, forcing Zen institutions to adapt to new conditions. In the 20th century, some Zen leaders lent support to Japanese nationalism and militarism during World War II, aiding imperial and colonial aggression throughout East and Southeast Asia. This legacy continues to prompt reflection and critique. At the same time, reformers sought to renew Zen training and open its practices to lay practitioners.

From the early 20th century, Japan promoted Zen abroad through cultural diplomacy, and writers such as D. T. Suzuki (1870–1966) introduced it to European and American audiences. Backed by Japan’s imperial reach and its efforts to present Zen as the essence of Japanese culture, the tradition gained international visibility earlier than Chan, Thien, or Seon. After World War II, teachers such as Shunryu Suzuki (1904–1971) and Hakuun Yasutani (1885–1973) established communities in the West, while lay-oriented movements like the Sanbo Kyodan created new models for practice outside the monastery. Today, Zen centers flourish across Europe, the Americas, and beyond, offering traditional forms of monastic discipline as well as new adaptations for lay life.

Japanese Zen is a tradition rooted in the Chinese Chan heritage, shaped by Japanese culture, and transformed again as it spread worldwide.

Foundational Texts and Records

It’s often said that the meditation schools reject “words and letters,” stressing practice over scripture. In reality, their founders were highly literate, and the traditions produced a vast body of writings that remain central to their identity. Language was not dismissed but used in distinctive ways—to point beyond concepts, to preserve encounters between teachers and students, and to transmit teachings.

The Platform Sutra is among the most important Chinese Chan texts. It is attributed to the Sixth Patriarch Huineng (638–713), who presents the teaching of sudden awakening, which became a cornerstone of Chan thought. Beyond its doctrinal importance, it was copied, recited, and studied in monasteries and temples, shaping how practitioners understood their tradition. Collections of gong’an (Jap.: koan) also circulated widely, including the Blue Cliff Record, the Gateless Gate, and the Book of Equanimity. These works recorded the stories and dialogues of early masters, often framed with poetic commentary, and served as training tools for centuries.

Monastic communities also compiled and preserved “recorded sayings” (Ch.: yulu), the sermons, conversations, and instructions of their teachers. Many combine sharp exchanges with refined literary style, revealing the dual role of monasteries as centers of discipline and learning. “Lamp histories” (chuandeng lu), such as the Jingde Record, were another key genre, as they presented lineages and teaching episodes to authorize communities and inspire practice. These texts, along with personal writings like the letters of Dahui Zonggao (1089–1163) to his students, continue to show how teachers conveyed the dharma, both in person and from afar.

As Chan spread across East Asia, the role of texts varied. Korean Seon monasteries made gong’an collections and hwadu practice central to training. Vietnamese Thien blended Chinese records with indigenous writings and devotional elements. In Japan, Dogen’s Shobogenzo became the foundational text of Soto Zen, presenting reflections on practice and realization, while Rinzai monasteries emphasized mastery of gong’an anthologies.

The meditation schools used language as a tool of practice. Texts were recited in daily services, chanted in ritual, memorized, and explained in dharma talks. Their words and letters remain integral to training today, studied in monasteries and lay centers alike.

Women in the Meditation Schools

Women have long practiced within the meditation schools, but their presence is often absent from official lineages and recorded histories. Genealogies of patriarchs were compiled to establish institutional authority, and in doing so, they largely erased women. The meditation schools have no lineage of matriarchs. Despite this, historical records do preserve glimpses of the women who shaped the tradition.

In China, figures such as Zishou Miaozong (1095–1170) were recognized for their profound realization and teaching abilities. Records describe her pointed exchanges with male students, challenging assumptions about authority in the meditation hall. In Japan, Mugai Nyodai (1223–1298) became the first female abbess of a Zen convent in the 13th century, helping to establish communities for women practitioners. Korea and Vietnam also had active traditions of nuns, though their contributions were less often recorded.

In modern times, the visibility of women in the meditation schools has grown dramatically. Daehaeng (1927–2012) was one of the most respected Seon Buddhist teachers in Korea. She became widely known for her penetrating insight into people and her story of personal struggle growing up during the Japanese occupation. Shundo Aoyama (b. 1933) leads one of Japan’s largest training monasteries for women, continuing a long but often hidden lineage of female practitioners. Cheng Yen (b. 1937), founder of the Tzu Chi Foundation in Taiwan, exemplifies how Chan-inspired compassion can be practiced through social action.

Women from East Asian meditation traditions are a powerful presence at the Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women’s biennial conference, and many are supporting the reestablishment of full bhiksuni (Skt.; Pali: bhikkhuni) ordination for Theravada and Tibetan nuns. Many Western temples and meditation centers affiliated with East Asian Meditation schools are increasingly recognizing the need to bring women’s lineages to light. The Rochester Zen Center in New York, for example, includes in its lineage chant a striking acknowledgment:

And to the unknown women,

centuries of enlightened ones,

whose commitment to the dharma

nourishes and sustains our practice—

you who have handed down the light of dharma,

we shall repay your benevolence!

This poetic aspiration captures what history often doesn’t: Women have always been present in the meditation schools, transmitting the dharma with the same clarity and commitment as their male counterparts.

Aesthetics and the Arts

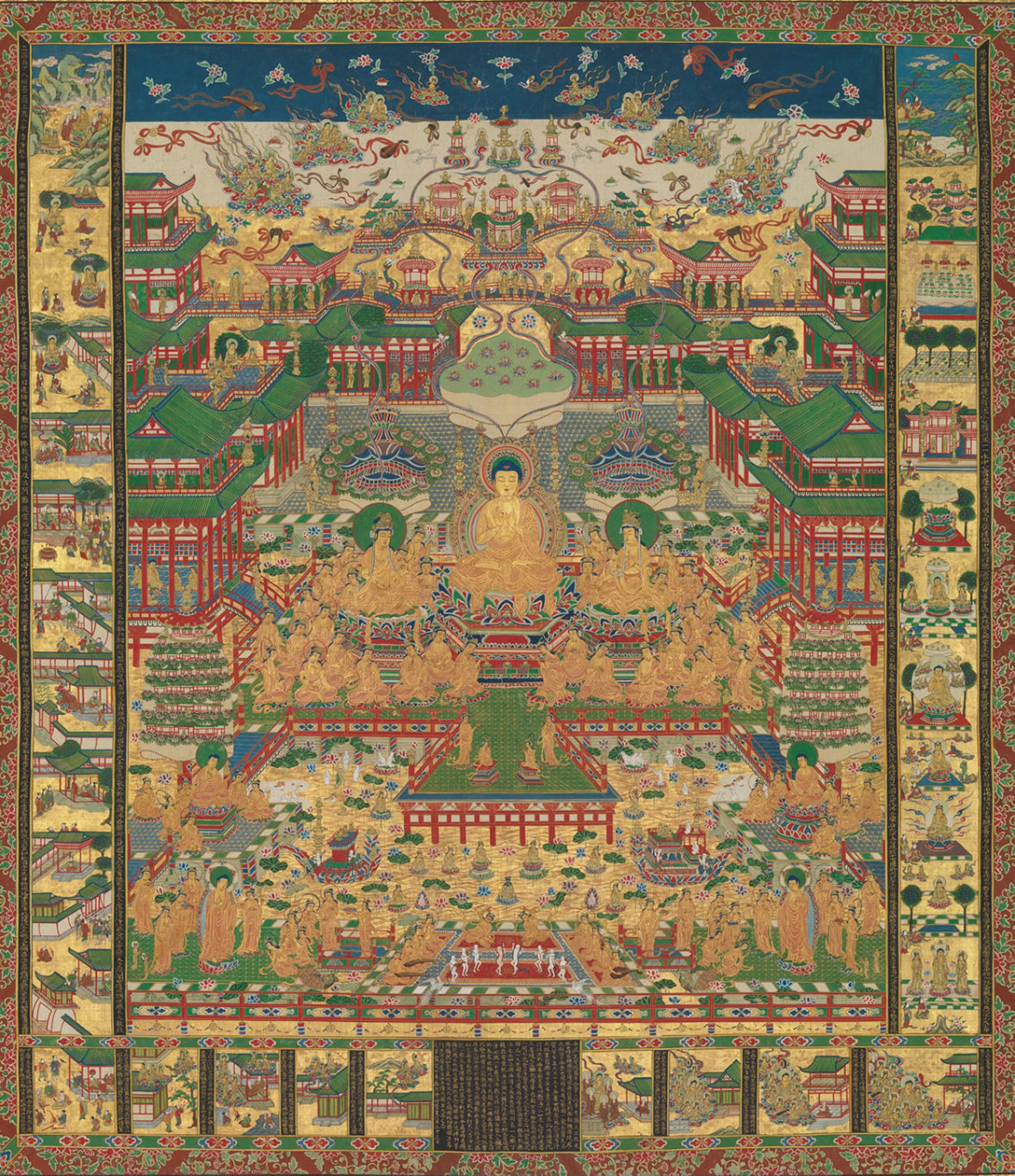

From their beginnings, Chan and the many Buddhist meditation schools that it influenced used art as a form of teaching and practice, not just as an ornament. Poetry, painting, music, architecture, and ritual performance conveyed the spirit of direct insight, aiding the practice of meditation itself.

Chan monks created ink paintings and calligraphy marked by spontaneity and restraint. A single brushstroke was treated as an expression of realization, capturing the immediacy of mind in action. Monks also composed poetry as a way of conveying meaning beyond conventional explanation. These poems are sometimes included in the recorded dialogues of the historical masters. Chanting and the recitation of sutras and verses gave voice to the dharma, uniting sound and meaning into practice.

In Korea, Seon monasteries developed architectural styles that ensured monasteries were in harmony with the mountains and forests. In these spaces, the natural and the transcendent meet. Seon monks were also poets, and their verses—sometimes austere, sometimes playful—continue to be read as extensions of Buddhist practice. Chanting rituals, often accompanied by bells, drums, and wooden percussion instruments, gave musical form to the lives of monastics and temple dwellers. To this day, the sound of the Buddhist wooden fish being struck in rhythm with chanting fills the early morning air of many deep valleys.

Vietnamese Thien cultivated liturgical chants and ceremonial music, blending meditative recitation with melodic forms and devotional practice. Temple rituals combined text, sound, and movement to create a full-bodied expression of the dharma. These forms helped anchor Thien in communal and civic life, allowing practice to extend beyond the meditation hall and into the fabric of society.

In Japan, Zen aesthetics had a profoundly influential impact. Monasteries supported calligraphers and painters, and the sensibility of simplicity and precision shaped gardens, architecture, and, later, the tea ceremony. Music also held a distinctive place: Zen chant traditions, known as shomyo, developed intricate melodic lines that continue to be performed in monastic settings. While these forms came to define what many people outside Japan think of as a “Zen style,” these arts should be understood as just one expression of the broader East Asian spectrum of Chan, Seon, and Thien creativity.

In all these cultural spaces, the arts functioned as a mode of practice and transmission. A brushstroke, a verse, a chant, or a garden arrangement could embody and directly communicate awakening. For the meditation schools, art and music were means by which the dharma was lived and shared.

Meditation Schools in the Modern World

The meditation schools have become global traditions. What began in Chinese monasteries has been carried forward by teachers, immigrants, and new generations of students, now reaching an international community. Today, Chan, Seon, Thien, and Zen are found in Europe, the Americas, Africa, and Oceania. Zen, in particular, gained a head start through Japanese cultural influence and postwar teachers, which helps explain why it remains the most prominent branch in the West.

The forms are diverse. Traditional residential monasteries continue to train monks and nuns, while lay communities practice in city temples, retreat centers, and online. Some groups maintain strict adherence to inherited rituals, while others experiment with hybrid forms that suit contemporary life. Secular meditation programs stripped of formal lineage have also emerged, drawing in those who seek practice without religious affiliation.

This global spread has raised questions of cultural adaptation and authority. Lineage transmission, once tightly bound to male monastic settings, now extends to lay teachers in international communities. Yet most Western groups are not formally recognized as part of the Asian institutions from which they draw inspiration. They are often treated as affiliated lay movements rather than official lineage holders, with transmission still tightly controlled in Asia.

The Kwan Um School, founded by Seung Sahn, and the Plum Village community, founded by Thich Nhat Hanh, are examples of communities that flourish internationally but remain outside the official lists of lineage holders. This distance brings both challenges and freedoms—Western temples receive no financial support from home institutions, yet they can govern themselves and are free from many traditional Asian conventions. Leaders such as Seon Master Soeng Hyang (Barbara Rhodes, b. 1948), who heads the Kwan Um School, embody a more flexible model of monastic authority.

The translation of teachings into new languages and communities has vastly increased access, but it has also introduced interpretive challenges. In some cases, such as Zen, the tradition has been borrowed for commercial purposes and simplified into lifestyle branding, prompting criticism from both Asian and Western practitioners. At the same time, many communities resist such dilution, emphasizing the ethical and communal dimensions of practice as essential to its integrity.

Non-Asian teachers now shape the future of these traditions in the West. From North and South America to Europe and Africa, teachers trained in Asian lineages adapt methods to new contexts while working to remain faithful to their origins.

In these ways, the meditation schools continue to evolve. They remain grounded in their core conviction—that practice is realization itself—while finding fresh expressions in new places, languages, and communities. The lineage that originated in East Asia is now unfolding as a global conversation.

Buddhism for Beginners is a free resource from the Tricycle Foundation, created for those new to Buddhism. Made possible by the generous support of the Tricycle community, this offering presents the vast world of Buddhist thought, practice, and history in an accessible manner—fulfilling our mission to make the Buddha’s teaching widely available. We value your feedback! Share your thoughts with us at feedback@tricycle.org.