What is Zen Buddhism?

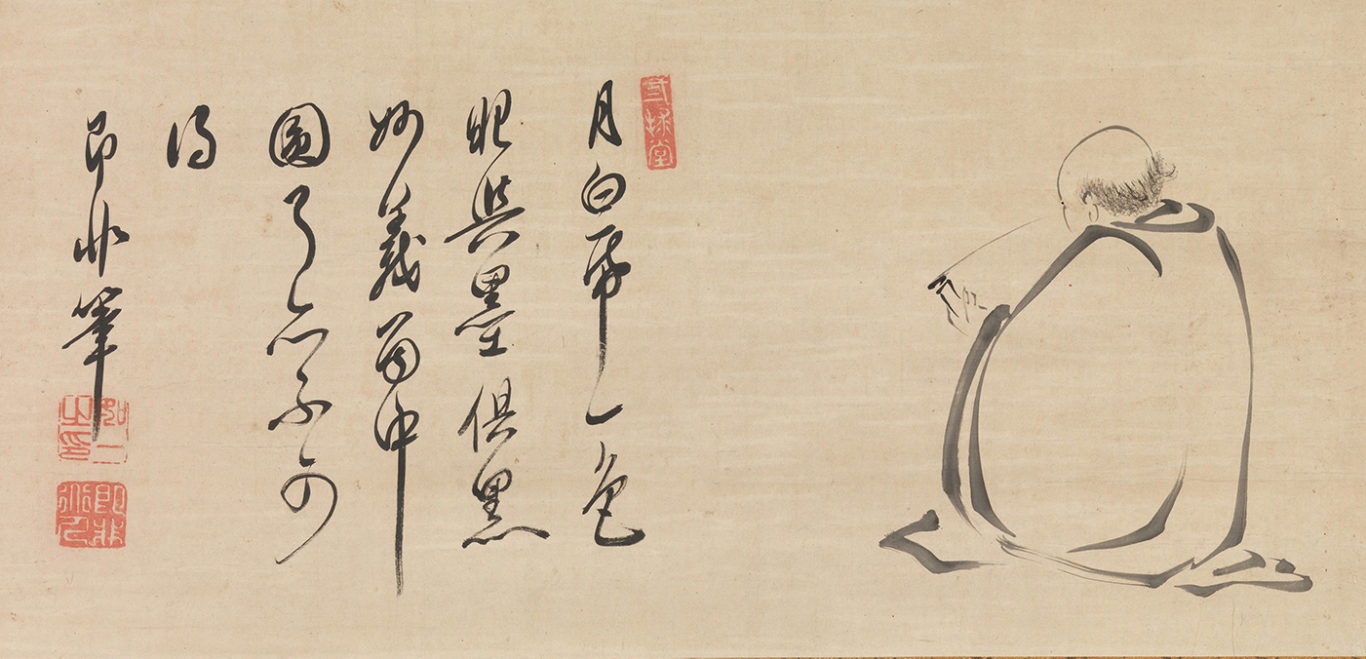

Reading a Sutra by Moonlight by Sokuhi Nyoichi (Chinese: Jifei Ruyi) depicts the Chinese monk Yinyuan Longqi (1592–1673), known for founding the Obaku sect of Zen in Japan. | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Harry G. C. Packard Collection of Asian Art

Zen is the Japanese name for a Buddhist tradition practiced by millions of people across the world. Historically, Zen practice originated in China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, and later came to in the West. Zen takes many forms, as each culture that embraced it did so with their own emphases and tastes.

Traditionally speaking, “Zen” is not an adjective (as in, They were totally zen). Zen is a Japanese transliteration of the Chinese word Chan, which is itself a transliteration of dhyana, the word for concentration or meditation in the ancient Indian language Sanskrit. (Zen is Seon or Son in Korean and Thien in Vietnamese.) When Buddhism came to China from India some 2,000 years ago, it encountered Daoism and Confucianism, absorbing some elements of both while rejecting others. Chan is the tradition that emerged. In this context, Chan refers to the quality of mind cultivated through sitting meditation, known as zazen in Japanese, which many Zen Buddhists consider to be the tradition’s most important practice.

Zen is as diverse as its practitioners, but common features include an emphasis on simplicity and the teachings of nonduality and nonconceptual understanding. Nonduality is sometimes described as “not one not two,” meaning that things are neither entirely unified nor are they entirely distinct from one another. Zen recognizes, for example, that the body and mind are interconnected: they are neither the same nor completely separate. Nonconceptual understanding refers to insight into “things as they are” that cannot be expressed in words.

To help students discover nonduality without relying on thought, Zen teachers use koans—stories that appear nonsensical at first but as objects of contemplation in zazen lead to a shift of perspective from separation to interconnectedness. Because teachers play such an important role in Zen, the tradition emphasizes reverence for its “dharma ancestors,” or lineage, influenced by Confucianism’s teaching of filial piety. At the same time, throughout Chinese history, Zen challenged other Confucian ideas by stressing the absolute equality of all beings and women’s capacity for enlightenment.

Ultimately, Zen Buddhism offers practitioners ways to heal their hearts and minds and connect with the world. These ways have differed over time and from culture to culture. In medieval Japan, for example, Zen monks served as doctors to the poor, doling out medicine and magic talismans, and as ministers, offering funerals and memorial services. Today in the West, many practitioners come to Zen looking to gain peace of mind and mental clarity through meditation. Like all schools of Buddhism, Zen begins with an understanding that human beings suffer, and it offers a solution to this suffering through recognizing the interconnectedness of all beings and learning to live in a way that aligns with this truth.

Tricycle is more than a magazine

Gain access to the best in sprititual film, our growing collection of e-books, and monthly talks, plus our 25-year archive

Subscribe now