The Grijpstra and de Gier crime novels

Janwillen Van De Wetering

Soho Press

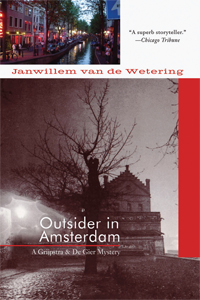

“Outsider in Amsterdam,” 2003 (1975), 290 pp., $13.00 paper

“The Blond Baboon,” 1996 (1978), 215 pp., $13.00 paper

“The Maine Massacre,” 2003 (1979), 231 pp., $13.00 paper

“The Amsterdam Cops: Collected Stories,” 2003 (1983–1999), 254 pp., $13.00 paper

“Hard Rain,” 2003 (1986), 313 pp., $13.00 paper

In the library of the school where I work, I recently came across several paperback reprints of detective novels by the Dutch author Janwillem van de Wetering, who died in July 2008. Of his thirty titles in English, half are works of crime fiction featuring a pair of Amsterdam-based detectives, Henk Grijpstra and Rinus de Gier. When the books first came out in the 1970s and 1980s, I started a few but never finished them. Some years later, I discovered that van de Wetering also wrote three books about his adventures as a wandering seeker occasionally drawn to Zen. He spent a year in a Rinzai Zen monastery in Kyoto, traveled widely, did a stint as a cop in Amsterdam, and landed at Walter Nowick’s Zen community, in Maine. Van de Wetering and his wife ultimately settled nearby, although the Zen community dissolved. (For a profile of Nowick, see Tricycle, Spring 2009. [LINK]) When I picked up van de Wetering’s books this time, I read the reviewers’ comments on the back covers: “Masterly Zen mysteries”; “Quirky characters and Zen outlook”; “combination of Dutch sense and Buddhist sensibility”; “Our author…[is] sly as a Zen koan.” Who could resist? I took home a stack of books to have another look.

In the library of the school where I work, I recently came across several paperback reprints of detective novels by the Dutch author Janwillem van de Wetering, who died in July 2008. Of his thirty titles in English, half are works of crime fiction featuring a pair of Amsterdam-based detectives, Henk Grijpstra and Rinus de Gier. When the books first came out in the 1970s and 1980s, I started a few but never finished them. Some years later, I discovered that van de Wetering also wrote three books about his adventures as a wandering seeker occasionally drawn to Zen. He spent a year in a Rinzai Zen monastery in Kyoto, traveled widely, did a stint as a cop in Amsterdam, and landed at Walter Nowick’s Zen community, in Maine. Van de Wetering and his wife ultimately settled nearby, although the Zen community dissolved. (For a profile of Nowick, see Tricycle, Spring 2009. [LINK]) When I picked up van de Wetering’s books this time, I read the reviewers’ comments on the back covers: “Masterly Zen mysteries”; “Quirky characters and Zen outlook”; “combination of Dutch sense and Buddhist sensibility”; “Our author…[is] sly as a Zen koan.” Who could resist? I took home a stack of books to have another look.

Van de Wetering was a good writer. This time around I found myself amused, charmed, sometimes bored (when the plot slowed)—but also puzzled about what exactly made the books so Zen in the reviewers’ minds. Was it the calm attention that de Gier (the good-looking sergeant whom women tend to invite home) and Grijpstra (higher in rank, older, melancholic) pay to their investigations—not counting time out for boozing—or their philosophical observations on the chaos of the world they occupy? Was it words like “detachment,” “breakthrough,” and “lovingkindness” sprinkled through the text (though van der Wetering never explains their meaning in context)? Longer Zen-like reflections also appear in the books, but they, too, mostly pass without elaboration. In “The Maine Massacre,” the commissaris (the detectives’ boss) muses, “What on earth is ‘right’? I’ve often been tempted to think right equals nothing. Perhaps nothing is the ultimate wisdom. Now, zero means absolute nothing and the idea it symbolizes is a void, an utter void.”

Van de Wetering weaves a self-portrait into every crime novel. There is his resemblance to de Gier (handlebar mustache; appealing, odd trains of thought) and, on another level, to the quiet, profound commissaris, probably the most “Zen” of all his characters. Other repeating threads include van de Wetering’s experience on the Amsterdam reserve police force, his love of jazz, his ideas about ideas. Even more telling, perhaps, is his response to an interviewer who asked, “What did life in the monastery give you?” “Nothing,” van de Wetering replied. “It just relieved me of much ballast. My ideas were ignored. But it taught me that what mattered was what I was doing at any moment, peeling potatoes or weeding garden beds.”

Why “nothing”? Was he playfully referring to the nothing of sunyata— “the ultimate wisdom,” as the commissaris put it? Why “just relieved”? Questions to ponder while picking up a Grijpstra–de Gier. I particularly recommend the short-story collection “The Amsterdam Cops” and the novels “The Maine Massacre” and “The Blond Baboon” as starters.