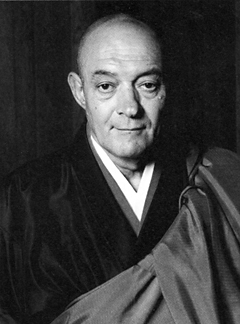

In the first installment of a new regular feature by students about their teachers, John Kain talks about John Daido Loori Roshi. We encourage readers to send us reflections on their teachers.

Daido Roshi is a tall, lanky, olive-skinned Italian American from Jersey City, New Jersey, with the requisite Buddhist shaved head. Daido is seventy-three years old, charismatic; when he walks into a room, people tend to stop talking. He’s telling me a story about his late Japanese teacher, Maezumi Roshi.

“I’d been living at Zen Center for a number of years,” he told me. “The practice was hard, hour after hour of zazen (meditation) and long days working to keep the Zen Center financially secure. But I loved it and came, after time, to have confidence in my own spiritual wisdom. At some point I figured that I’d come to understand death. So during a private and casual conversation I told Maezumi I’d ‘sorted out the whole death thing.'”

As Daido is telling me this story he rubs the perimeter of a sun-faded anchor tattoo on his left forearm—a remnant of his navy days—as if tracing the outline of his life. “Maezumi looked me straight in the eye and said, ‘So you’ve figured out the great matter of life and death, have you?'” Daido continued. “Before I could answer, he leapt from his seat, knocked me to the floor, and began choking me. At first I began to laugh. I’m big and Maezumi was a little guy, so I wasn’t that worried. But quickly it got very hard to breathe and I could feel the ends of his fingers pushing deeper into my windpipe. I began to choke and sputter and I realized that Maezumi was serious, so I began to struggle, but he was incredibly strong. Without thinking, I managed a roundhouse right punch to Maezumi’s jaw and knocked him to the floor. He didn’t stop laughing for five minutes and then said, ‘Conquered death! Ha!’ I had bruises on my neck for a week.”

The late Shunyru Suzuki Roshi, the Japanese master who started the first Buddhist training monastery in America and the author of the classic Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, wrote: “The teaching given by Shakyamuni Buddha during his lifetime was accommodated to each disciple’s particular temperament, and to each occasion’s particular circumstances. For each case there should be a special remedy. According to circumstances, there should even be teachings other than those which were given by Buddha. In light of this, how is it possible to interpret and pass down an essential teaching that can be applied to every possible occasion and individual temperament?”

I’ve been Daido’s student for eight years, and have been studying at Zen Mountain Monastery for over ten, but I’ve never been choked by my teacher. In the beginning I was actually a little envious of that story. It seemed the epitome of “the Zen encounter,” like the ones I’d read about in the ancient texts of old Chinese masters vanquishing their disciples’ illusions. My relationship with Daido has been largely quiet and gentle, though I never asserted that I had conquered death. Most of us come to a teacher with a bundle of expectations, both conscious and unconscious, about how that teacher should be, how they should act. Usually the first few years are spent dismantling those preconceived notions.

♦

From A Rare and Precious Thing: The Possibilities and Pitfalls of Working with a Spiritual Teacher, © 2006 by John Kain. Published by Bell Tower and used with permission.