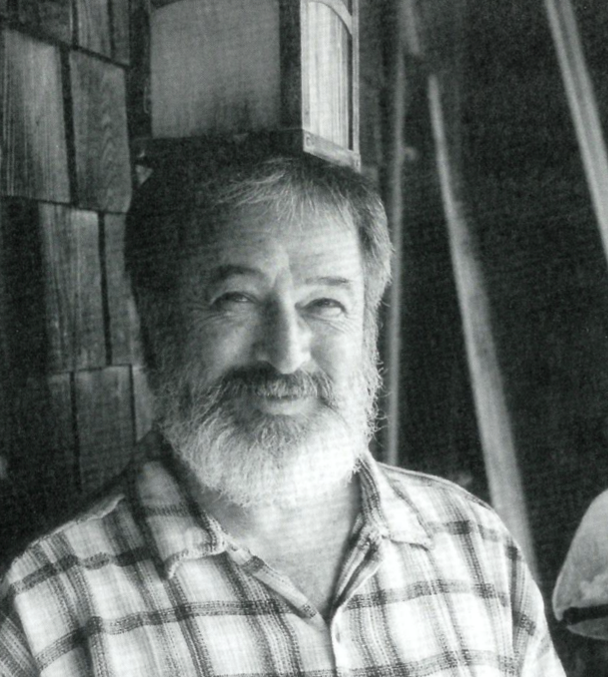

Bill Porter lived for three years in the early seventies as a Buddhist monk in Taiwan where he began his translations of poetry by the famous Chinese poet-recluse Cold Mountain. Porter’s mentor in this undertaking was the Buddhist scholar and translator John Blofield. After leaving monastic life, he married a Chinese woman and continued his translation work. Years later, Porter began the first of many long journeys in mainland China that he chronicled for radio audiences in Hong Kong and Taiwan. He produced over 1,100 short programs about different Chinese locales, embellishing his narratives with details from Chinese history and culture. In recent years he has focused on China’s great Zen monasteries, traveling to scores of the remaining abodes of famous ancient Zen teachers.

Porter’s main books of translation, published under the name Red Pine, include The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma (North Point Press), The Zen Works of Stone House (Mercury House), The Clouds Should Know Me by Now: Buddhist Poet Monks of China (Wisdom Publications), and his latest, The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain (Copper Canyon). Road to Heaven: Encounters with Chinese Hermits (Mercury House) is published under the name Bill Porter because it is not a book of translation. This interview was conducted in Ukiah, California, north of San Francisco, by ANDY FERGUSON.

Tell me about your background and how you became interested in Buddhism.

My dad was a bank robber. He and his gang were knocking off banks in the South and worked their way north to the Michigan area. There they got in a shoot-out with police. All the robbers were killed except my dad, who was wounded in the knee and lost his kneecap. Then, of course, he went to prison. In the meantime, the family farm down South got sold and when Dad got out he used his portion to get into the hotel business in Texas. He then became a top hotel magnate and the family got very rich. So my childhood was one of wealth, with maids and big homes. First we lived in L.A., then later we lived near Coeur D’Alene in Idaho.

Dad bought Bing Crosby’s house. He liked Democratic Party politics and actually became head of the Democratic Party in California. He toyed with the idea of running for office, but he had this problem with his background, so he’d just get himself nominated for different offices and then turn down the nomination. Eleanor Roosevelt nominated my dad, Arnold Porter, to be President of the United States on national TV at the 1956 Democratic Convention. The Kennedy brothers, Ted and Robert, used to visit our house. John never came there, but when he was in the White House Dad used to get drunk and call him on the phone. He’d just do it to show off to us kids. My sister and brother and I went to fancy private schools, but even at a young age I hated it all. It was so phony, with everyone caught up in wealth and ego and power. It all seemed to me to be so hollow. Later, my dad divorced my mother and subsequently we lost everything. It all went into receivership. My sister and brother had a very difficult time learning to live without lots of money. But as for me, I was actually relieved when this happened. After some unsuccessful stints in junior college I served for three years in the Army as a clerk in a medical unit in Germany, and when I got out the GI Bill paid for my college education at UC Santa Barbara. When I encountered Buddhism, I didn’t have any problem understanding exactly what it was talking about. The whole thing was quite clear to me. After four years of college, I could have gone further into graduate school, but at that point all I wanted to do was become a Buddhist monk.

You’re recognized as an authority on Chinese religious culture not only among many Westerners, but among Chinese as well. For example, the head of the mainland Chinese Buddhist Association, Abbot Jing Hui of Bailin Monastery, has directed his head monk Minghai to translate your English book Road to Heaven: Encounters with Chinese Hermits into Chinese. Many Chinese learn about their traditions from you. In this case, your book is a window on the phenomenon of Chinese hermits. Talk about the perception of hermits in China and whether it is very different from our regard for them in the West.

The hermit tradition is actually one of the most important parts of Chinese society. We [in the West] almost always think of hermits as misanthropes, as people who want to step out of, and have nothing to do with, society—whereas in China the hermit has always been seeking the wisdom with which to guide society. My conversations with hermits in China led me to conclude that [for them] seclusion was like going to graduate school. Afterwards they can teach. Seclusion did not necessarily mean individual seclusion. It could also occur in a relatively secluded monastery. Persons who could “break the mold” and become teachers almost always required a period of seclusion for maturation. The Zen tradition represented one aspect of this tradition by producing these individuals en masse. You almost never hear of anybody who became a teacher by just working their way up through the ranks of an organization. This was true not only in Zen, but among other Buddhist schools such as Pure Land or T’ien-t’ai. It was true in Taoism as well. There was an awareness that to bring the teachings they had learned to fruition, individuals needed to be alone with them, and so Chinese hermits have been doing that. Nowadays, when I visit my hermit friends, I often find Chinese Communist officials visiting them too. One woman hermit I visited had six Communist officials in her hut, seeing if they could do anything to help her out. The Chinese previously maintained, and have recently revived, an awareness that these people were doing society a lot of good. They’re like a mountain stream that brings fresh water down into town. The water eventually reaches the town, no matter whether you pipe it down or it comes down as a spring.

In your book, Road to Heaven, it’s notable that at least one-half of the hermits you interviewed were women. How do you account for there being so many women hermits in China?

One of the reasons is because of the inequality between the sexes in China. It was a major decision for a family to allow a son to enter the clergy, since a son represented the parents’ social security. For daughters to marry out of the family, however, was expensive. It also represented a loss of labor to the family. Plus, the family had to make a big dowry payment. So it’s been easier for women to leave home to become hermits or enter religious orders for this reason. Sixty to seventy percent of the hermits I interviewed were women. It was very unlikely for a family to let a single son become a monk because he wanted to become one. If there was an extra son, however, it might be considered a good religious investment to let him become a monk.

You have a new book on the poetry of Cold Mountain out now. How did your interest in Cold Mountain come about and how did you come to translate his work?

I lived at a monastery in Taiwan run by Dharma Master Wuming, Chiang Kai-shek’s personal teacher. He gave me a copy of Cold Mountain poems that he had published. I liked them so much that I translated them myself. After I had done 150 of them, I wanted to publish them but didn’t know how to go about it. An Australian friend saw a lot of books on my bookshelf by John Blofield and said, “Why don’t you send them to him and ask him what to do with them?” So I did. John Blofield kindly answered my letter and we then began a relationship. Eventually I published three hundred of the poems and John Blofield provided the foreword for the book. Now, with my latest book, I’m revisiting those poems. It hadn’t occurred to me when I did the first book that when you translate a poem you have to write a poem.

I know that seems obvious, but it hadn’t really occurred to me. Now, after fifteen years, I feel I can translate a poem as a poem.

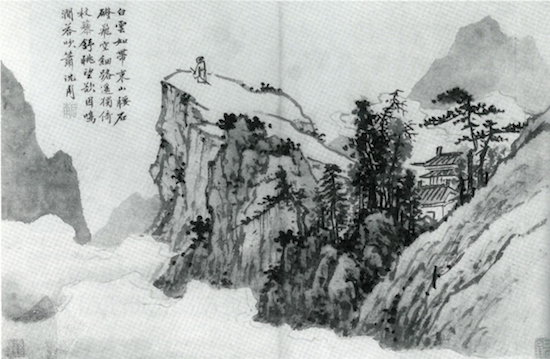

A hermit poet you’ve written about who had profound influence, not only in China, but also in Korea, was the Chinese Zen master Stone House. Can you talk about his place in the hermit tradition and why he came to have such a widespread influence?

Well, he was one of the exceptional Zen students who became a poet. Stone House had a genius for poetry that is unique. I’ve always said that he was the greatest of all the Chinese Buddhist poets. And although he was a hermit, he was a Zen teacher, too, and he taught individuals through his poetry. Stone House loved the hermit tradition, but managed to attract people to his hermitage just as if he was living downtown. He is a good example of how the hermit tradition affects society. By staying up on his mountain, he was able to affect the course of Zen in Korea. A prominent Korean monk came and studied with him at his hermitage and then took the robe and bowl of Stone House back to his country and established the Chogye Order, Korea’s main Zen tradition.

So Stone House was able to affect people by being a hermit, and his influence as a teacher was bound up in his skill as a poet. There were Zen masters in China who were his equal or even his superior in their Zen understanding, but nobody wrote a better poem.

What was it like to visit the place where Stone House lived?

One of the things I always try to do in China is “revisit the scene of the crime.” I go to the sites associated with figures that I admire. On one trip, I sought out the mountain where Stone House lived as a hermit. In the last five hundred years a road was actually built to the top of the mountain and now there’s a military electronic relay installation there. Within a few minutes after we arrived we were surrounded by the authorities there. But as soon as I whipped out my published translations of Stone House’s poems along with the original Chinese, the officer in charge told the soldiers to put away their guns. He then got out his machete and personally led me through the undergrowth to an old farmhouse made of rocks on the mountain. He said, “This is where those poems were written. When we moved here it used to be a little Buddhist temple.” There was a farmer living there who confirmed that this was where Stone House lived. The spring was still flowing right behind the hut, the only spring on the mountain. It was just remarkable to go to a site where someone you know lived a long time ago and find the same old hut there, with only a few bricks replaced or the roof having been repaired after falling in six or seven times since he lived there. That’s what I love to do in China. I love to visit these old places.

It sounds like the Chinese officer in charge was quite interested in helping you.

Even though there’s religious oppression going on in China, it is mainly a political oppression. It doesn’t have anything to do with the underlying cultural appreciation that remains with the people of China, even with the Communist Party officials at the local level. It goes to show that despite fifty years of Communist rule, the Chinese people themselves have an amazing appreciation for their own culture, their history, and the religions of China.