The perfect way is not difficult, only avoid picking and choosing.

—Seng-ts’an, “The Mind of Absolute Truth“

This world of dew

is a world of dew—

and yet, and yet…

—Issa

A spacious range of awake understanding is embraced by the two quotes found above. Seng-ts’an’s words are unquestionably true: in any moment free of preference, sufferings vanish. His poem describes a mind supple, peaceful, undefined by opinion and concept, yet one that does not turn its back to the world. The phrase “Sun-faced Buddha, Moon-faced Buddha” holds the same perception: warm or cold, bright or dark, constant or changing, whatever is is the heart’s true home. Yet Issa’s haiku, written after the death of his five-year-old daughter, makes its own claim, equally true. Yes, it says, existence is transience—but to know transience fully is to grieve for what passes, if what passes is what we love. Desire is the wish for anything to be other than it is. Grief, then, or anger, the empty stomach’s appetite or way-seeking mind, the urge to write or paint-any of these, not just erotic longing or material greed, can be forms of desire. We who exist in human form exist also amid human feeling. Issa’s sorrow—his desire that his daughter might still live—is surely lit by a moon-faced Buddha.

It has always seemed to me that an essential distinction in meaning exists between the choice of “detachment” and “nonattachment” in translating the same Pali word, anupadana. Detachment implies the extinction of feeling. In non attachment the river-life of emotion continues, only our relationship to it alters. The response to the passions isn’t driven by the small self’s benefit, but turns instead toward all beings’ well-being. This distinction strips from practice the risk of nihilism. It also clarifies what at times seems to need remembering: the taste of awakening is not flavorless, the energies of practice are not apathy or depression.

The middle way means living in accord with things as they are, with ourselves as we are. Whether in the realm of eros, physical hunger, intellectual curiosity, or those difficult-to-classify longings that lead to works of art or a life of practice, desire faces us toward life, as inevitably as a green leaf faces its branch toward the sun. Desire lures us into our lives, threads us into the fabric of interconnection. By pleasure and by pleasure’s anticipation, evolution attaches us to the fragrant world.

So often thought of as an expression of ego, desire is also ego’s antithesis. Ego wants to control, to believe that it can control—yet desire demonstrates time after time that the small self is not in charge of our lives. The Japanese poet Masahide wrote: “Barn burned down. Now I can see the moon.” What is a barn-conflagrating spark, if not an ally of practice?

Erotic desire, then, can be simply another face of the many-faced Buddha. Whatever the symbolic meanings of the stone-held or painted Hindu and Tantric figures in full sexual embrace, to look at them is to breathe a little more quickly. Compassion, passion, and empathy share one root, in life as in language—each requires that we feel. For compassion to come into being, we need to enter fully into human life. This, then, is one meaning of the Bodhisattva Vow: to agree to remain subject to desire, in this world, while acting within the field of the paramitas (the virtues that one has to perfect in order to fully awaken). “This very body,” wrote Hakuin Zenji, “with all its passions, is the body of the Buddha.” A practice understanding that leads to fearless opening.

For a poet, the allegiance to fearless opening is the only practice possible. Basho wrote that the life of poetry means lighting a fire in summer, swallowing ice cubes in winter. And there is Ikkyu.

Born at dawn on January 1, 1394, the illegitimate son of an emperor, Ikkyu spent his life sometimes behind the gates of various temples in and near Kyoto, sometimes behind the doors of the local brothel. In his seventies, he brought his young lover, the blind singer Mori, into a formerly abandoned temple that soon became a gathering place for poets, painters, and other artists. Ikkyu abhorred official trappings of power, burning his transmission papers, but when his old training monastery, Daitoku-ji, was destroyed, he accepted the abbacy and, with the help of the wide circle of disciples and admirers gained from his years in the world, rebuilt it, even while continuing to live mostly in his mountain temple with Mori. Ikkyu’s allegiance—as can be seen in his poems—was never to outer appearances, always to himself as he was, to things as they are:

Who can measure a master’s means of teaching?

Explaining the path, arguing Zen, the tongues of men

grow long.

I have always disliked piety.

In the dark, my nostrils wrinkle: incense before the Buddha.While alive, admit it: the passions never leave.

The fire of desire is the master of all that exists.

Spring comes each year.

New grasses answer the rising heat.Just as they are,

white dewdrops fall

on scarlet maple leaves.

Look—red dew.The mind-stream flows through its four rivers never the same.

Awakened Mind, Delusion—each entirely fills the

present and past.

Cold window, cold wind-blown snow. cold moon in the

earliest blossoms—

The drinker lifts his wine glass, the poet hums his poem.

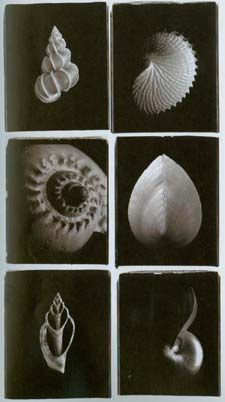

Portraits by Rembrandt, Vermeer, El Greco, and Diane Arbus, village scenes by Breughel, share a particular quality: an alloy of detachment and empathy seems to suffuse their gaze. Desire is not overtly in their subjects, who tend to look back from the frame without any seeming longing for change, nor is desire apparent in the artists’ relationships to their subjects. Their works feel, but do not interfere with, the fates of those they hold. Yet artmaking is born, at least in part, in some kind of wish—for the ambering of experience against time’s dissolution, for the creation or expression of beauty, for the discoveries or display of talent or of emotional, intellectual, or spiritual understanding. Artmaking, adding something to things as they are, must be placed in the world of desire. Beneath the serene artistic surface is a rapacity: like the Greek god Hermes inventing the first musical instrument from the bones and intestines of a stolen cow, the artist is in some aspects a hunter and thief—to make art, you must want.

To make art, you must want. Yet the work of art completed counterbalances attachment.

Yet the work of art completed counterbalances attachment. It is done. The artist lets it drop and walks away, and the painting or photograph, the sculpture or poem with which the artist has been so fiercely engaged, lets her or him go. It is the same for the viewer, the listener—great art takes us utterly, changes us utterly, then restores us to the condition of fundamental realization: we are as we are, the world is as it is. An intimate thusness. In this way, any work of art is the Zen master’s ink-brushed circle—emptiness and form embrace, made visible in all of its beginningless and endless parts.

Must the experience of desire, of preference, even of the recognition of beauty, be identical to the experience of attachment?

A monk asks, “The great wind blows everywhere. Why, teacher, do you use your fan?” The master continues fanning.

That fanning is an answer that comes from the world as it is. It is also the monk’s question, going on in the world as it is.

♦

Ikkyu poems adapted from translations by Sonya Arntzen.

Related: The Riddle of Desire: Introduction