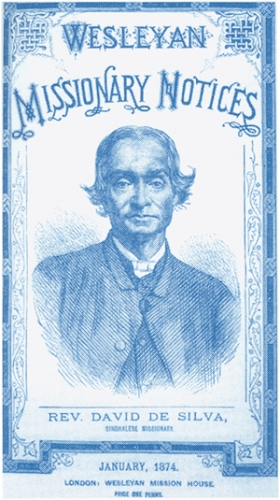

By seven o’clock on the morning of August 26, 1873, a crowd of some five thousand had gathered around a raised platform in the town of Panadure outside of Colombo, Ceylon—what is now Sri Lanka. On one side of the platform stood a table covered in white cloth and adorned with evergreens. This was the side occupied by the Christian party and its spokesman, Rev. David de Silva. The other side, more richly decorated, was filled by some two hundred Buddhist monastics and their spokesman, a monk named Gunananda. For the next two days, that platform would be the sparring ground for a heated debate over which religion would liberate the people of Ceylon: Buddhism or Christianity.

The Rev. de Silva spoke first, quoting Pali scriptures that declare there is no soul, that a person is only the aggregation of various impermanent parts. According to Buddhism, then, human beings have no immortal soul and are “on a par with the frog, pig, or any other member of the brute creation.” If there is no soul, there can be no punishment for sin or reward for virtue in the next life. Hence, he concluded, “no religion ever held out greater inducements to the unrighteous than Buddhism did.”

When it was his turn, Gunananda attacked the missionary’s knowledge of Pali, explaining that according to Buddhist doctrine, a person reborn was neither precisely the same as nor different from the person who had previously died. He then turned to the shortcomings of Christianity, noting that in the Book of Exodus, God instructs the Hebrews to mark their doors with blood so that he would know which houses to pass over as he killed the Egyptians’ firstborn children. The monk concluded that an omniscient god would not need such instructions. In the end, the five thousand onlookers declared Gunananda the winner. It was not the first time that Buddhists and Christians had debated the primacy of their respective faiths. Jesuit missionaries had challenged Buddhist doctrine in Japan, China, and Tibet. In each case, the Christians failed to conquer these lands or convert their peoples. But because Ceylon was a British colony, Gunananda’s denunciation of Christianity would have far-reaching ramifications. He painted the first broad strokes of what could be called Modern Buddhism.

The dharma that Gunananda sought to describe was not the result of a long historical evolution, but the Buddhism of the Buddha himself. Indeed, what I am calling Modern Buddhism seeks to distance itself from those forms of Buddhism that immediately precede it and even those that are contemporary with it. Its proponents viewed—and still view—ancient Buddhism, and especially the enlightenment of the Buddha 2,500 years ago, as the most authentic moment in the long history of Buddhism. It was also the form of Buddhism most compatible with the ideals of the European Enlightenment, ideals such as reason, empiricism, science, universalism, individualism, tolerance, freedom, and the rejection of religious orthodoxy—precisely those notions that have appealed so much to Western converts. It stresses equality over hierarchy, the universal over the local, and often exalts the individual above the community. In fact, what we regard as Buddhism today is a modern creation. Its widespread acceptance, both in the West and in much of Asia, is testimony to the influence of an array of figures from a variety of Buddhist lands, including the United States and Europe.

Gunananda’s presentation signaled important changes that would spread throughout the Buddhist world into the twenty-first century. In the first place, Gunananda was an educated monk who not only knew the sutras but had studied the Bible as well. Like him, the leaders of the various Modern Buddhist movements in Asia would be drawn from the small minority of learned monks and not from the vast majority who chanted sutras, performed rituals for the dead, and maintained monastic properties. Second, the Buddhism portrayed in the debate, and in Modern Buddhism more generally, had to do with technical doctrine and philosophy rather than daily practice. Indeed, Buddhism came to be portrayed—whether in Sinhalese, Chinese, or Japanese—as a world religion, fully the equal of Christianity in antiquity, geographical expanse, membership, and philosophical profundity, with its own founder, sacred scriptures, and fixed body of doctrine.

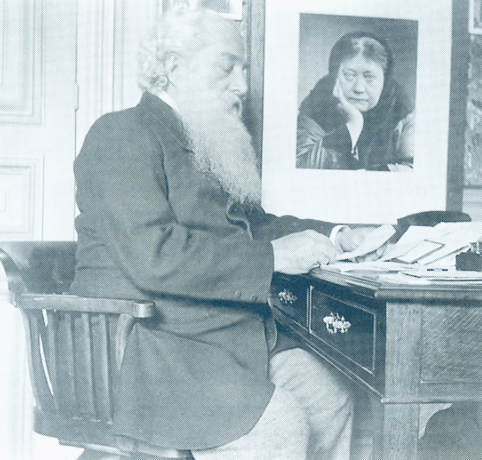

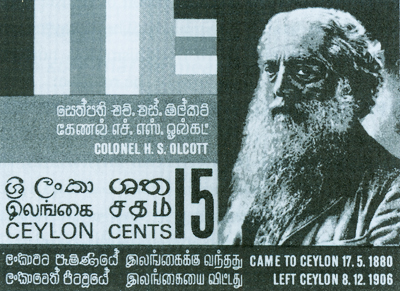

The debate made its impact in circuitous ways, but one person who read about it was to have a huge bearing on the contours of Modern Buddhism: In 1878 Colonel Henry Steel Olcott, cofounder, with Helena Blavatsky, of the Theosophical Society, saw an embellished account of the debate published in Boston. Blavatsky and Olcott had set out to found a scientific religion, one that accepted new discoveries in geology and archaeology while touting an ancient and esoteric system of spiritual evolution. By 1878 Blavatsky and Olcott were claiming affinities between Theosophy and the wisdom of the East, specifically Hinduism and Buddhism. And inspired by Olcott’s reading of the account of Gunananda’s defense of the dharma, they were determined to join the Buddhists of Ceylon in their battle against Christian missionaries. In 1880 they sailed to Ceylon and both took the vows of lay Buddhists.

While Blavatsky’s interest in Buddhism remained peripheral to her Theosophy, Olcott embraced his new faith, being careful to note that he was a “regular Buddhist” rather than a “debased modern” Buddhist, and he decried what he regarded as the ignorance of the Sinhalese about their own religion. “Our Buddhism was that of the Master-Adept Gautama Buddha . . . the soul of the ancient world-faiths,” he later wrote. “Our Buddhism was, in a word, a philosophy, not a creed.”

In order to help restore true Buddhism to Ceylon and stem the tide of Christianity, Olcott adopted many of the missionaries’ techniques. He founded the Buddhist Theosophical Society and helped found the Young Men’s Buddhist Association. In 1881 he published The Buddhist Catechism, modeled on works used by the missionaries. Olcott shared the view of many enthusiasts in Victorian Europe and America who saw the Buddha as the greatest philosopher of India’s Aryan past and regarded his teachings as a complete philosophical and psychological system based on reason and restraint, opposed to ritual, superstition, and priestcraft. It demonstrated, they argued, how the individual could live a moral life without the trappings of institutional religion. This Buddhism was to be found in texts rather than in the lives of the contemporary Buddhists of Ceylon, who in Olcott’s view had deviated from the original teachings.

This would not be his only contribution to Modern Buddhism. In 1885, Olcott set out on the grander mission of healing the schism he perceived between “the Northern and Southern Churches,” that is, between the Buddhists of Ceylon and Burma (Southern) and those of China and Japan (Northern). Olcott believed that a great rift had occurred in Buddhism 2,300 years earlier and that if representatives of the Buddhist nations would simply agree to his list of fourteen “Fundamental Buddhistic Beliefs,” then it might be possible to create a “United Buddhist World.” These principles were sufficiently bland as to be soon forgotten. But Olcott was again prescient: many later Modern Buddhists would attempt to reduce Buddhism to a series of propositions. Olcott was also the first to try to unite the various Buddhisms of Asia into a single organization, an effort that bore fruit long after his death with the founding of the World Fellowship of Buddhists in 1950.

Olcott left one more legacy. Authority in Buddhism is usually a matter of lineage, traced backward in time from student to teacher, ending with the Buddha himself. A lineage of Modern Buddhism might begin with Gunananda (who clearly saw himself as representing the original teachings of the Buddha), then be picked up by Colonel Olcott, then by a young Sinhalese named David Hewaviratne (1864—1933). At the age of nine he sat with his father in the audience of the Panadure debate, cheering for Gunananda. He met Blavatsky and Olcott during their first visit to Sri Lanka in 1880 and was initiated into the Theosophical Society four years later. In 1881 he changed his name to Anagarika Dharmapala (“Homeless Protector of the Dharma”), and though he remained a layman until late in life, he wore the robes of a monk.

Dharmapala became Colonel Olcott’s closest associate and achieved international fame after a bravura performance at the World’s Parliament of Religions, held in conjunction with the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. His eloquent English and ability to quote from the Bible captivated audiences as he argued that Buddhism was clearly the equal, if not the superior, of Christianity in both antiquity and profundity. Moreover, his meetings with other Buddhist delegates to the parliament, such as the Japanese Zen priest Shaku Soen, and with American enthusiasts of Buddhism like the philosopher Paul Carus, helped shape the course of things to come.

Dharmapala spread the lineage of Modern Buddhism to China when he stopped in Shanghai on his journey back from the World’s Parliament of Religions. There he met Yang Wen-hui (1837—1911), a civil engineer who had become interested in Buddhism. Yang organized a lay society to disseminate the dharma by carving woodblocks for the printing of the Buddhist canon (a traditional form of merit-making). After serving at the Chinese embassy in London, he resigned in order to devote all his energies to the publication of Buddhist texts.

Yang did not think it possible for Chinese monks to go to India to help restore Buddhism there, as Dharmapala asked, but he suggested that Indians be sent to China to study the Buddhist canon. Here is yet another element of Modern Buddhism. Dharmapala felt that the Buddhism of Ceylon was the purest version of the Buddha’s teachings and would have rejected as spurious most of the texts that Yang was publishing. Yang, on the other hand, felt that the Buddhism of China was the most authentic, such that the only hope of restoring Buddhism in India lay in returning the Chinese canon of translated Indian texts to the land of their birth. The ecumenical spirit found in much of Modern Buddhism does not preclude championing one’s own form of the religion.

Buddhist monks in China faced different obstacles than those faced by monks in Ceylon. The challenge came not so much from Christian missionaries, though they had a strong presence in China, but from a growing community of intellectuals who saw Buddhism as a form of primitive superstition impeding the country’s entry into the modern world. Buddhism had periodically been regarded with suspicion by the state, and such suspicion intensified in the early decades of the twentieth century, when Buddhism was denounced by both Christian missionaries and Chinese students who returned from abroad with the ideas of Dewey, Russell, and Marx.

Buddhist leaders responded by founding schools to train monks in the Buddhist classics, who would in turn teach the laity (as Christian missionaries did). Although most of these academies were short-lived, they trained many of the future leaders of Modern Buddhism in China, who sought to defend the dharma through founding Buddhist organizations, publishing Buddhist periodicals, and leading lay movements to support the monastic community.

Meanwhile, Buddhist intellectuals in late nineteenth-century Japan strove to show the relevance of Buddhism to the interests of their nation. They promoted a New Buddhism that was fully consistent with Japan’s attempts to modernize and expand its realm. Buddhism had been attacked in the early years of the Meiji as a foreign and anachronistic institution, riddled with corruption and superstition and impeding progress. This New Buddhism was represented as both purely Japanese and purely Buddhist—more Buddhist, in fact, than the other Buddhisms of Asia. It was also committed to social welfare, urging the foundation of public education, hospitals, and charities. Indeed, Buddhist leaders were consistent in their call to restore true Buddhism (which existed only in Japan, they said) throughout the rest of Asia, beginning with the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 and continuing to the defeat of Japan in 1945.

One of the leading figures of Japan’s New Buddhism was Shaku Soen (1859-1919). Ordained as a novice of the Rinzai Zen sect at the age of twelve, he received dharma transmission and authority to teach at twenty-four. Seeking to combine Buddhist training and Western-style education, he attended university and then traveled to Ceylon to study Pali and live as a Theravada monk. Upon his return, he coedited a book called The Essentials of Buddhism—All Sects. Like many of the leading figures of Modern Buddhism, Soen was devoted to teaching meditation to laypeople. At the World’s Parliament of Religions in 1893, he described his country’s position as follows:

… the Japanese are people with abundantly loyal and patriotic spirits… Buddhism has exercised great influence on Japanese spirituality and has had influence on successive emperors… Buddhism is a universal religion, and it closely corresponds to what science and philosophy say today…

Soen and his visit to the United States were to have a huge influence on another proponent of Zen in the West: his lay disciple D. T. Suzuki, whose writings have provided many Americans with an introduction to Buddhism.

If the domain of Modern Buddhism encompassed rationalism, individualism, nationalism, and science, it also envisioned more active and visible roles for women. Perhaps no issue has been more important in this regard than the question of the ordination of women as nuns. The Buddha is reported to have asserted that women are capable of following the path to enlightenment, but to have only grudgingly permitted an order of nuns. This order eventually spread to Sri Lanka, Burma, China, Vietnam, Korea, and Japan. However, it was difficult for the order of nuns to withstand periods of social upheaval, and although it survives in China, Korea, and Vietnam, it has died out in Sri Lanka and in most of Southeast Asia. Modern Buddhists have sought to revive it.

As with all Buddhist reform movements over the centuries, Modern Buddhism represents itself as a return to the teachings of the Buddha, or better, to his ineffable experience beneath the Bodhi tree on a full moon night in May. Implicit in this claim, however, is a criticism of traditional Buddhism, of the Buddhism of turn-of-the-century Asia. The supposed resurrection of the original dharma allowed Modern Buddhists to concede many of the charges made by Buddhism’s critics, whether they were Orientalists, colonial officials, Christian missionaries, or Asian secularists. They saw contemporary Buddhists as benighted idolaters crushed by centuries of superstition and exploited by an effete and corrupt monastic order. Rather than defending the Buddhism they knew, many of the leading figures of Modern Buddhism accepted the claim that the religion had suffered an inevitable decline since the master passed into nirvana. The time was ripe to remove the encrustations of the past centuries and return to the essence.

This Buddhism is seen, above all, as a religion dedicated to bringing an end to suffering. Suffering was often interpreted by Modern Buddhists not as the sufferings of birth, aging, sickness, and death, but of those caused by poverty and social injustice. The Buddha’s ambiguous statements on caste were selectively read by Europeans and Asians alike to portray him as a crusader against inequality based on birth rather than merit. Because of this view, Modern Buddhism came to promote the social good in the form of rebellion against political oppression (especially by colonial powers), projects on behalf of the poor, and through the more general claim that Buddhism was the religion most compatible with the technological and economic benefits that result from modernization.

Modern Buddhists also argued that the Buddhism of the Buddha was free from the veneration of images. They described reverence of Buddha images as the simple expression of thanksgiving for his teachings, given in full recognition that the Buddha had long ago entered into nirvana. But this interpretation was at odds with traditional practice. Relics of the Buddha are believed to be infused with his living presence and thus capable of bestowing all manner of blessing upon those who venerate them. That Modern Buddhists (especially in the West) either ignored this practice or dismissed it as superstition points to the influence of the colonial legacy of Christian missionaries, who consistently labeted Buddhists as idolaters.

Modern Buddhists proclaimed superiority over Christianity in the domain of science. Such disparate figures as Dharmapala in Sri Lanka, T’ai Hsu in China, Shaku Soen in Japan, and more recently the Dalai Lama have asserted the compatibility of Buddhism and Western science. They argue that the Buddha himself denied the existence of a creator deity, rejected a universe controlled by the sacraments of priests, and set forth a rational approach by which the world operates according to the law of cause and effect. Elements of traditional cosmology that conflicted with science (such as a flat earth) were dismissed as local myths that had nothing to do with the Buddha’s original teaching.

Modern Buddhists have sought to liberate the teachings of the Buddha from centuries of cultural and clerical ossification to reveal a Buddhism that was neither Theravada nor Mahayana, neither monastic nor lay, neither Sri Lankan, Japanese, Chinese, nor Thai. This was a Buddhism whose essential teachings could be codi-fied. For the first time in the history of Buddhism, writers began to summarize the religion in a single book. There was Olcott’s Buddhist Catechism, Paul Carus’s The Gospel of the Buddha According to Old Records (which D. T. Suzuki translated into Japanese), and Christmas Humphreys’ 1951 work, Buddhism. Humphreys, who had founded the Buddhist Society in London in 1924, explained that his interest was in a “world Buddhism as distinct from any of its various Schools,” and that “only in a combination of all Schools can the full grandeur of Buddhist thought be found.” Such a “world Buddhism,” transcending all regional designation and sectarian affiliation, had not existed before the advent of Modern Buddhism.

This was the only sense in which Buddhism could be regarded as a universal religion. But as such, many of the distinctions of other forms of Buddhism faded. For example, whereas Buddhism had not existed before without the presence of an ordained clergy, many of the leaders of Modern Buddhism were laypeopie, and many of the monks who became leaders of Modern Buddhism did not always enjoy the respect, or even the recognition, of the monastic establishment. Indeed, one of the characteristics of Modern Buddhism is that teachers—including women teachers—who were marginal in their own cultures became central on the international scene.

Still, Modern Buddhism did not dispense with monastic concerns. Rather, it blurred the boundary between the monk and the layperson, with laypeople taking on the traditional vocations of elite monks: the study and interpretation of scriptures and the practice of meditation. In this sense, Modern Buddhism has shifted emphasis away from the community (especially the community of monks) to the individual, who was able to define a new identity, sometimes even designing new robes that marked a difference in status between the categories of monk and layperson.

Meditation came to be the essential practice of Modern Buddhism. In their guest to return to the origin of Buddhism, Modern Buddhists looked to the image of the Buddha seated in silent meditation beneath a tree, contemplating the ultimate nature of the universe. This practice allowed Modern Buddhists to dismiss the rituals of consecration, purification, and exorcism so common throughout Asia as extraneous elements that had crept into the tradition. Meditation allowed Modern Buddhism again to transcend local expressions, which required form and language. At the same time, the very silence of meditation provided a medium for moving beyond sectarian concerns of institutional and doctrinal formulations by making Buddhism, above all, an experience.

The emphasis on meditation marked one of the most extreme departures of Modern Buddhism from previous forms. The practice of meditation had been the domain of monks throughout Buddhist history, and even here, meditation was merely one of many monastic activities.

Much of what we regard as Buddhism today is Modern Buddhism. And Modern Buddhism seems to have begun in part as a response to the threat of modernity, as perceived by certain Asian Buddhists, especially those, like Gunananda, who had encountered colonialism. Yet these Modern Buddhists were very muchproducts of modernity themselves, influenced by the rise of the middle class, the power of the printing press, and the ease of international travel. Many of these leaders were deeply involved in independence movements and identified Buddhism with the interests of the state, as the exiled Dalai lama does today. Yet together they have forged an international Buddhism that transcends cultural and national boundaries, and they have created a new generation of intellectuals who write the dharma in English.

It is perhaps best to consider Modern Buddhism not a universal religion beyond sectarian borders but a Buddhist sect itself. There is Thai Buddhism, there is Tibetan Buddhism, there is Korean Buddhism, and there is Modern Buddhism. Unlike previous forms of national Buddhism, however, this new sect does not stand in a relation of mutual exclusion to the others. One may be a Chinese Buddhist and a Modern Buddhist, but one also can be a Chinese Buddhist without being a Modern Buddhist. Like other Buddhist sects, Modern Buddhism has its own lineage, doctrines, and practices. And like other Buddhist sects, it has its own canon of sacred scriptures—scriptures that have created a Buddhism so new, yet also so familiar…▼