The one-l lama,

He’s a priest.

The two-l llama,

He’s a beast.

And I will bet

A silk pajama

There isn’t any

Three-l lllama.

–Ogden Nash

In 1956, the British firm Secker & Warburg published The Third Eye: The Autobiography of a Tibetan Lama. It remains in print to this day, the best-selling book about Tibetan Buddhism.

The Third Eye introduced Tibet and Tibetan Buddhism to hundreds of thousands of readers in Europe and America in the 1950s and ’60s. Over the last four decades, readers around the world have discovered the book in sidewalk kiosks, airport newsstands, and university bookstores. It is a work that has evoked sympathy for the plight of Tibet under Communist occupation and even inspired some to become Tibetologists, professional scholars of Tibet. Its author was Lobsang Rampa, the son of one of the leading members of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama’s government.

Rampa had spent his earliest years as a schoolboy in Lhasa. He studied Tibetan, Chinese, and the art of carving wood for printing blocks. He enjoyed kite-flying, the national sport of Tibet, whose season began on the first day of autumn, signaled when a single kite rose from the Potala, the great palace of the Dalai Lama. On Rampa’s birthday, astrologers had predicted an eventful future for the child: “A boy of seven to enter a lamasery, after a hard feat of endurance, and there to be trained as a priest-surgeon. To suffer great hardships, to leave the homeland, and go among strange people. To lose all and have to start again, and eventually to succeed.”

Young Lobsang was admitted to the Temple of Tibetan Medicine, where he underwent a rigorous course of study that emphasized mathematics and memorization of the Buddhist scriptures. Proving himself an excellent student, he was chosen to receive the esoteric teachings and serve as a repository of knowledge against the prophesied day when Tibet would fall under an alien cloud. Under the tutelage of the great Lama Mingyar Dondup, he began a period of intensive training designed to impart in a few years what a lama would normally learn over the course of a lifetime. In order to further his instruction by hypnotic methods, Mingyar Dondup prescribed a surgical procedure to channel the power of clairvoyance.

The operation was performed on the boy’s eighth birthday. A hole was drilled in his skull to create another eye—a Third Eye that allowed him to see auras. After the surgery, he was summoned to the Potala, where he met privately with the Thirteenth Dalai Lama. Lobsang was reminded of the great work that lay before him in preserving the wisdom of Tibet for the world.

Shortly after his twelfth birthday, Lobsang passed a punishing round of examinations and was certified as a medical priest. On an expedition in search of medicinal herbs, he stopped at a monastery where the monks built box kites large enough to bear the weight of an adult. Lobsang made several flights in such kites, and later suggested design modifications to improve their airworthiness to the monastery’s Kite Master.

Following a further series of examinations on his sixteenth birthday, the young monk was promoted to the rank of lama. He studied anatomy with the Body Breakers, the disposers of the dead who chop up corpses and feed them to vultures. When he had passed initiation as an abbot, he was again summoned by the Dalai Lama, who now instructed him to leave Tibet immediately and go to China, saying:

“The ways of foreigners are strange and not to be accounted for. As I told you once before, they believe only that which they can do, only that which can be tested in their Rooms of Science. Yet the greatest Science of all, the Science of the Overself, they leave untouched. That is your Path, the Path you chose before you came to this Life.”

The Third Eye ends with Lobsang Rampa looking back for the last time at the Potala, where a solitary kite is flying.

I recently used The Third Eye in a seminar for first-year undergraduates at the University of Michigan. The students were unanimous in their praise of the book. They judged it more realistic than anything they had previously read about Tibet, appreciating the detail about “what Tibet was really like.” Many of the things they had read about seemed strange until then; these things seemed more reasonable when placed within the context of a lama’s life.

It was not that the things Rampa described were not strange; it was that they were so strange that they could not possibly have been concocted. . . .

But were there really man-bearing kites in Tibet? Did priests really only ride white horses? Did cats really guard the temple jewels? Are the priests in Tibet vegetarian? Did they really perform the operation of the Third Eye?

Unfortunately, perhaps, the answer to each of these questions is No.

Publisher Fredric J. Warburg had first met the shaven-headed and bearded author at the press’s offices in London. The lama had introduced himself in fluent English. He had read Warburg’s palm, correctly told him his age, and informed him that his firm was the karmically appropriate one for his book. In spite of this assurance, Warburg retained doubts about the manuscript’s antecedents. He sent copies to almost twenty Tibet experts, among them several who had lived in Lhasa during the period covered in the book. None had ever heard of Lobsang Rampa or Lama Mingyar Dondup.

On a subsequent occasion, Warburg greeted the lama with a foreign phrase, only to receive a blank look in return. When informed that he had been addressed with the Tibetan for “Did you have a pleasant journey?” Rampa fell to the floor in apparent agony, rising to explain that during the war, in order to prevent himself from divulging secrets to the Japanese, he had hypnotically blocked his own knowledge of Eastern languages. To that day, the sound of his native tongue was enough to reinflict their tortures. When Warburg confronted Rampa with the scholars’ objections, offering him the option of publishing the book as a work of fiction, Rampa continued to insist that it was entirely factual. Secker & Warburg then issued the book with a preface that began, “The autobiographical account of the experiences of a Tibetan lama is such an exceptional document that it is difficult to establish its authenticity”

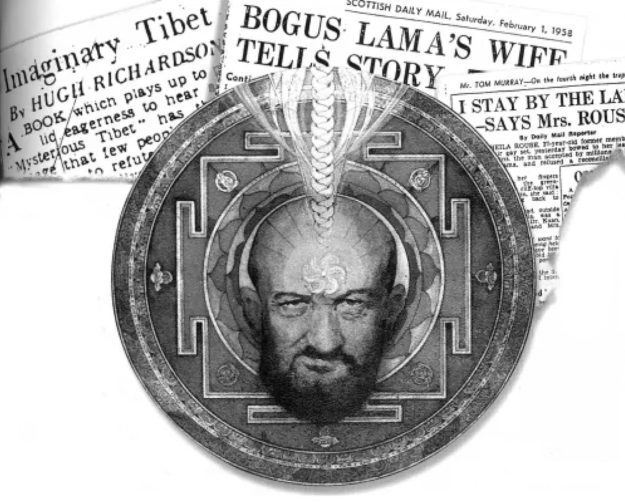

“This is a shameless book,” was the opening line of Tibet scholar David Snellgrove’s review. Heinrich Harrer, who had recently spent seven years in Tibet, wrote a review so scathing that the book’s German publisher threatened a libel suit. Tibetologist Hugh Richardson, whose earlier report on the manuscript had induced the publishing house of E. P. Dutton to turn Rampa down, had this to say in the Daily Telegraph:

There are innumerable wild inaccuracies about Tibetan life and manners which give the impression of Western suburbia playing charades.

The samples of the Tibetan language betray ignorance of both colloquial and literary forms, there is a series of wholly un-Tibetan obsessions with cruelty, fuss and bustle, and, strangely, with cats . . . .

. . . One can regard only as indifferent juvenile fiction the catchpenny accoutrements of magic and mystery: the surgical opening of “the third eye”; the man-lifting kites; the Abominable Snowman; the Shangri-la valley and eerie goings-on in caverns below the Potala.

Rampa’s book sold 300,000 copies in the first eighteen months after publication. It went through nine hardback printings in two years in the U.K. alone. When scholars asked for a chance to speak with the author, Warburg refused.

But events were closing in on the mysterious lama. In January 1957, Scotland Yard asked him to present a Tibetan passport or a residence permit. Rampa moved to Ireland. One year later, the scholars retained the services of Clifford Burgess, a leading Liverpool private detective.

Burgess’s report, when it came in, was terse. Lama Lobsang Rampa of Tibet, he determined after one month of inquiries, was none other than Cyril Henry Hoskin, a native of Plympton, Devonshire, the son of the village plumber and a high school dropout.

According to the detective, Hoskin had been in London ever since moving there in 1940 and finding work at a “surgical fittings manufacturer.” Later the same year, he moved on to a position as a clerk at a correspondence school. During his time with this firm, Burgess stated, “He became more and more peculiar in his manner, and among many strange things he did was—(1) he used to take his cat out for walks on a lead (2) during this period he began to call himself KUAN-SUO and he had all the hair shaved off his head.” Burgess found it more difficult to account for the years 1950 through 1953, noting only that during this period Hoskin had been seen by one acquaintance to whom he represented himself as a “criminal and accident photographer.” He resurfaced in 1954 as a resident of the London neighborhood of Bayswater under the name of Dr. Kuan-Suo.

The report on Cyril Hoskin concluded with this statement: “Until he went to live in Dublin there is no evidence of his ever having left the British Isles.”

Elsewhere, the detective related that after changing his name, the former Hoskin had written a rhyme to his supervisor at the correspondence school: “You may wonder why I go on so/But will you please remember I am Kuan Suo.” He was fired shortly thereafter, and some time later approached a literary agent with two manuscripts, one on “surgical fittings”—otherwise known as corsets—and one on Tibet, to be called The Third Eye.

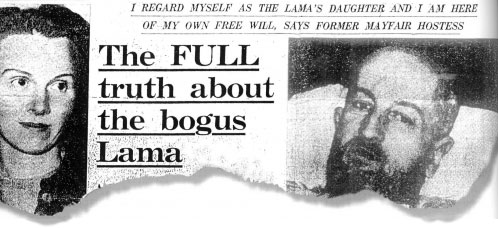

“The FULL truth about the Bogus Lama,” screamed the Daily Express. During the first week of February 1958, the Bogus Lama was the main story in the British press. When Cyril Hoskin was finally located in Dublin, he refused to meet with the press on doctor’s orders because his heart was too weak. He sent word through his wife, however, that he had written the book for the real Dr. Kuan, a Tibetan whose family was in hiding from the Chinese Communists and whose whereabouts could therefore not be revealed. But another explanation was soon provided, both fuller and more mysterious.

When The Third Eye was reprinted, it contained “A Statement by the Author” that began, “In the East it is commonly acknowledged that the stronger mind can take possession of another body.” It went on to recount that in late 1947, Hoskin had felt a strange and irresistible compulsion to adopt Eastern ways of living. He legally changed his name and quit his job. In June 1949, he suffered a concussion when he fell out of a tree trying to photograph a bird. When he regained consciousness, he was not himself. His memories of his life as an Englishman had completely vanished, replaced by full memories of the life of a Tibetan from babyhood onward.

Over the next four years, the author further addressed the question of just how a Tibetan lama’s spirit came to inhabit the body of an English high school dropout. The account was extensive enough to occupy two more books.

According to Doctor from Lhasa, the sequel to The Third Eye, Lobsang Rampa departed Tibet for China, where he enrolled in a medical college. Putting his skills at both healing and flying to good use, he enlisted in the war against Japan as the pilot of an air ambulance. Shot down, Rampa ended up in a prison camp near Hiroshima. On the day the bomb was dropped, he escaped and stole a fishing boat, drifting into the Sea of Japan.

The Rampa Story opens fifteen years later, in 1960. In Tibet, the lamas had located a remote network of caves and tunnels through astral exploration. They were engaged in transporting the most sacred artifacts of the faith to this new, secret site. Though by this point Lobsang Rampa was himself physically established in Canada, he continued to keep in touch with his homeland via telepathy. The lamas were thus able to inform him of his next task: to write a book “stressing one theme, that one person can take over the body of another, with the latter person’s full consent.”

Rampa recounted that the fishing boat had eventually run aground on the Asian mainland, near Russian army lines. After being arrested and tortured by the Communists, he was released, but was seriously injured in a road accident. His soul was transported to a world beyond the astral to recuperate. There he met the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, who urged him to return to earth and continue his work. The problem was that his body was in deplorable condition.

The Inmost One explained: “We have located a body in the land of England, the owner of which is most anxious to leave. His aura has a fundamental harmonic of yours. Later, if conditions necessitate it, you can take over his body.” He cautioned his disciple: “You will return to hardship, misunderstanding, disbelief, and actual hatred, for there is a force of evil which tries to prevent all that is good in connection with human evolution.”

Rampa communicated astrally with his host-to-be. The Englishman confided that he hated life in Britain because of the favoritism of the class system, but had always had an interest in Tibet and the Far East. He was duly instructed to fall out of a tree and to knock himself unconscious. Then, with great difficulty, Rampa entered the Westerner’s body, rose to his feet, and was helped inside by the man’s wife.

When he had recovered sufficiently, he took various free-lance jobs to support his new wife and cat. It was when inquiring about a job as a ghostwriter that he was encouraged by a literary agent to write his own book. “Me, write a book? Crazy! All I wanted was a job providing enough money to keep us alive and a little over so that I could do auric research, and all the offers I had was to write a silly book about myself.”

But at the insistence of his agent, he undertook the arduous task of writing The Third Eye.

Hoskin/Rampa would go on to write ten more books, which were increasingly devoted to discussions of auras, extraterrestrials, future wars, the lost years of Jesus, and expositions of the Law of Kharma. He published a volume entitled Living with the Lama, dictated telepathically to him by Mrs. Fifi Greywhiskers, and donated all the royalties from My Visits to Venus to the Save a Cat League of New York. His books have sold more than four million copies.

The influence of The Third Eye, in particular, has been far-reaching. It inspired some to attempt to perform the operation of the third eye on themselves—in one unhappy case in the Netherlands, with a dental drill. In the 1970s, Tibetan lamas teaching in Europe and North America were invariably asked whether they knew Lobsang Rampa and if they themselves had undergone surgery to open the third eye. Rampa’s fixation on auras, the astral, and crystal balls has done much to forge the dubious link between Tibetan Buddhism and the New Age.

Yet this very link has brought Tibet to the attention of an audience of Western readers who might otherwise have been unconcerned, a multitude who would have had no interest in Tibetan culture or its tragic fate had it not been for Rampa’s New Age trappings. And a number of prominent scholars of Tibetan Buddhism, who shall remain nameless, have confessed that they were first inspired to pursue their life’s work by reading The Third Eye.

For such people, who have since graduated to more orthodox works of Tibetiana, the word “fraud” is easy to apply to The Third Eye’s author. Yet opportunism or simple self-aggrandizement falls somewhat flat as an explanation of Hoskin’s motive, for there seems little doubt that he really did believe himself to be Lobsang Rampa.

Perhaps it is not in terms of material greed, but rather in a more complicated and deeply rooted desire, that the mystery of Cyril Hoskin’s Oriental masquerade should be assessed. In his third eye, he visualized the fantasy of Tibet in such a way that he could himself be embodied within it. Tibet: a place with the power to allow him to assume a new identity without leaving England—a place where the class-conscious son of a Devon plumber could become the scion of Lhasa aristocracy, and a fitter of surgical goods could become a surgeon; where a correspondence school clerk could lay claim to a medical degree, and a criminal and accident photographer could see auras.

Viewed in retrospect from the 1990s, from these times in which Caucasian followers of Tibetan Buddhism are routinely recognized as incarnations of lamas (numerous children and an action-movie star among them), it may even seem that the tragedy of Hoskin’s imposture was a simple lack of authorization. Hoskin’s ideas about possession and astral travel owed more to a homegrown spiritualism than to any recognized Vajrayana school—and yet teachings such as phowa (“transference of consciousness”), as described in Evans-Wentz’s 1935 Tibetan Yoga and Secret Doctrines, could have provided him with an authentic Tibetan precedent, had he just known where to look.

In The Wizard of Oz, the Scarecrow asked for a brain and was rewarded with a diploma. Would Lobsang Rampa’s career have been different if his claim to knowledge had only been certified, by a Tibetan lineage holder—or by those three magic letters: Ph.D.?

Rampa died in 1981 in Calgary, where the Canadian Rockies provided a fitting resting place for this exile to the land of snows. To the end, he insisted that everything in his books was true. His circle of disciples and millions of readers around the world seem never to have been in doubt. Those who knew him invariably noted the depression in the center of his forehead.