We sometimes hear abortion talked about within our society as the “new Civil War.” Perhaps that idea is apt, because people are now literally being killed over this issue. The difficulty is that we have two sides, neither of which feels able to give an inch to the other. We have within our society a deep contestation over two different kinds of rights: the right to life, and the right of a woman to make decisions concerning what happens to her own body. Our attitudes tend to become crystallized in one or the other of these two camps. But in my opinion, we do not need an ideological or religious war over abortion. The Japanese give us an example of another approach. Not that the great American debate about abortion can necessarily be resolved with a Japanese solution; nevertheless, I want to suggest that in Japan the issue of abortion as a social reality has been worked out over the course of recent history without sacrificing its religious dimension.

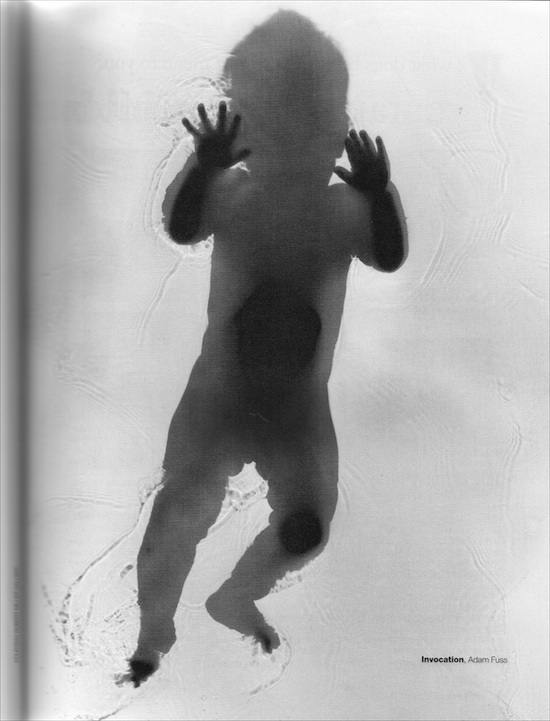

Following World War II, during the American occupation of Japan, abortion was made legal as long as a doctor stated that it was necessary for the physical or mental health of the woman involved. That has been the law in Japan since 1948, and there is no serious challenge to that law today. Nonetheless, rituals have developed over centuries (largely within Buddhist contexts, and increasingly since 1948) whereby women, and men as well, can make an after-the-fact apology to the aborted fetus. Through ritual they can express their sense of moral guilt, even as they find some relief from that guilt. The Japanese call this ritual mizuko kuyo. Mizuko means “water child,” and kuyo is the ancient Buddhist ritual for making an offering.

While I was in Japan in 1975, I would often ask Japanese Buddhist monks what they thought about abortion, and I got these very puzzling answers: “Of course we can’t take life. Buddhist law doesn’t allow us to do that. On the other hand, a woman shouldn’t have to have a baby if she doesn’t want to. A child should not have to be born into a family that doesn’t want it. We must have compassion.” From these responses, I realized that there was a great deal of ambivalence toward the issue of abortion on the part of the Buddhist clergy. During this same time, spending the year in Kyoto, I often went to the hillsides and saw many memorial sites for the bodhisattva Jizo. These little stone images look like children and perhaps partially for that reason are especially connected with the memorialization of children. In Japanese cities, Jizo shrines are commonly found at crossroads. In rural areas they are located at riverbanks or where the land meets the sea. The physical location is important—symbolizing a crossroads from life to life, through death. There are many of these old statues in such places. When asked about their purpose, people visiting these Jizo shrines would tell me, “They are for remembering dead children.” And I began to realize—given that the mortality rate for children in Japan was not terribly high—that the word child was being used to refer to what we in the United States would call a fetus.

At the time, there was no debate about abortion in Japan. Books on abortion didn’t exist. The contrast was startling—that was the year of Roe versus Wade—but gradually I began to see that, in a sense, Japanese society had come to a working solution to the issue of abortion.

In Japan, there is seemingly no inherent incompatibility between a strong family system and access to abortion, but contrary to contemporary assertions, it is not quite true that abortion has always been easily available. In the 1840s, during the Edo period, there was a movement of scholars known as Kokugaku, or “National Learning,” whose work suggests that abortion was, at that time, a highly contested matter. We know from demographers both in Japan and in the West that at that time Japan was in a phase called the “Population Plateau.” Between 1721 and 1846, the Japanese population, which had been rising steadily, suddenly leveled off for a 125-year period, and hardly went up at all. Why? During the same period China’s population doubled. Population experts have investigated this phenomenon a great deal, but none of the usual theories—wars, plague, famine – seem to apply. Japan was right in the middle of its great peace—no wars outside, no wars inside—and there was hardly any plague there Japan during that period.

The case for famine is stronger. We certainly know of local famines, particularly in northeastern Japan, but demographers generally agree that although the famine was serious, it was not serious enough to greatly effect the population. Therefore, it cannot quite explain why the population did not grow. The explanation, therefore, must have been that the Japanese were, during that 125-year period, practicing a form of birth control. When we see polemics against the practice of birth control through abortion and through infanticide, we can see that, indeed, the population was controlling its birthrate. This was done through what is called mabiki.

Literally, mabiki means “pulling the spaces” and is a term used by rice farmers to refer to the extraction of certain seedlings from a rice paddy to let other seedlings grow better. In other words, culling. During this time in Japan, the daimyo (feudal warlords) were telling people that they should produce as many children as possible, presumably to increase their own tax base. However, parents were deciding that they had the right to “extract” certain children. “Pulling the spaces” was the euphemism for abortion and infanticide during that period. While resistance to this hypothesis has come from the Japanese Marxists, who have said, “No, that can’t possibly be so—the population was decimated by starvation, the cruel government, and so forth,” that assertion seems to be without much support. In looking at Japanese society today, it seems difficult to imagine that people back then were practicing infanticide on a significant scale. Yet the facts seem incontrovertible.

Isn’t the prohibition against killing—the precept against taking life—basic to Buddhist teaching? Surely this is so. But a religion is not only its ethical system, not only its Ten Commandments or its set of precepts, but also its worldview. There was something in the Buddhists worldview that made the situation in Japan different from that in America: the simple fact that people in Japan believed, for the most part, in the notion of rinne, reincarnation, or transmigration through many lives. The concept of rinne posited that a life taken through abortion or infanticide would go to the gods and the buddhas and, at an appropriate time, come back into this world. In that sense, there was nothing ultimate and final about the taking of life. You were, to use a modern metaphor, putting that child “on hold.” You were asking that child to wait. The assumption that at an appropriate time the child would return to this world to a welcoming family expressed a worldview that had a considerable impact on the degree of mental and moral tolerance toward abortion and infanticide. This moral tolerance could be made even more agreeable to the psyche and to the mind by doing something for the sake of the aborted child through the bodhisattva Jizo.

My sense is that a cult of Jizo, for the sake of dead or aborted children, has been maintained by women in a rather informal way for centuries, probably since as early as the medieval period. After having had an abortion, a woman can address the departed child through Jizo; she can explain, for example, that she did not really want to give it up but that life was such that she had no real option. And, in some sense, just by acknowledging this in front of the image, the message is that she still cares; even now, her mind and heart are attentive to that life. She has no ill will. Women often speak about abortion as a painful necessity—painful emotionally, painful physically—but a necessity nevertheless. It is yet another one of the sad incongruities of life.

“Pulling the spaces” was a term used by rice farmers to refer to the extraction of certain seedlings from a rice paddy to let other seedlings grow better…. It was also the euphemism for abortion and infanticide.While abortion was illegal in Japan, women could not openly admit they were performing the Jizo ritual to memorialize an aborted fetus. Referring to it as a rite for “dead children” provided a kind of cover. But after the legalization of abortion in 1948, women could openly admit that they had had abortions. Today, in many instances, people will bring “siblings” of the aborted fetus to the cemetery, because it is considered appropriate to let living children know that, in the worlds of the gods and the buddhas, there are others who, in some spiritual sense, are part of the family as well. Some Jizo shrines have layer upon layer of statues, each with its own red bib, a little copy of the Heart Sutra, flowers, clothing, pinwheels, and things that are connected to childhood: pacifiers, costume jewelry, and the like. Written messages to various Jizos say Gomen nasai, “Please forgive me,” an apology to the child. This is said to a child toward whom one feels that some offense has been committed. The practice has become routinized, something that most people accept as part of what should be done.

How is all this applicable to the abortion issue in the United States? In America, I find an increasing interest in breaking through the impasse that grips our society. But the question raised so frequently is: “Is it necessary to adopt the whole Buddhist framework, the metaphysical baggage of reincarnation, in order to find the Japanese Buddhist rituals beneficial?”

Gary Chamberlain, a theologian at a Jesuit university, argues that there is a way to approach abortion other than that taken by Rome and the American bishops up to the present time. He suggests that Japanese Catholic bishops have shown much more compassion for women and the choices they face in real life. When he went to Japan to explore and investigate abortion, Chamberlain concluded that the Catholic Church itself could learn from Japanese practice. He suggests that, without adopting the Buddhist view of transmigration, Catholics in America could develop a ritual, somewhat like that for mizuko, that would be therapeutic rather than guilt-intensifying for women who had had abortions.

One final question—because it’s often asked of me—is whether this is not merely another case of the “slippery slope,” the argument sometimes used by ethicists to suggest that any moral leeway leads downward to more and more base practices. With regard to abortion, the “slippery slope” is often thought to have started with contraceptives. They, too, were originally considered immoral and were even illegal in some states. According to this argument, after accepting contraceptives, people eventually become inured to the practice of abortion. Next, proponents of the “slippery slope” reason, people will be practicing infanticide. But the slippery slope argument assumes that people’s morality always goes down.

The Japanese history of abortion offers an example of moral practices going the other way. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Japanese practiced birth control almost entirely through infanticide, when there was no other real option. In the twentieth century, the Japanese have virtually eliminated infanticide, substituting it with abortion. Now, more and more, abortion is being supplanted by contraception. Condom machines, for example, can often be found on street corners. So here is a movement—from infanticide to abortion to contraception—that goes up the slippery slope. The Japanese case is admirable not only because it offers a kind of social solution to the problem of abortion, but because that solution has prevented Japan from becoming socially divided over this whole issue.

A hymn attributed to the Buddhist priest Kuya (903-972) portraying the plight of deceased children standing on the banks of a river in Sai in remote Northern Japan.

This is a tale that comes not from this world,

But is the story of the Riverbank of Sai

By the road on the edge of Death Mountain.

Hear it and you will know its sorrow.

Little children of two, three, four,

Five —all under ten years of age—

Are gathered at the Riverbank of Sai

Longing for their fathers and mothers;

Their “I want you” cries are uttered

From voices in another world.

Their sorrow bites, penetrates

And the activity of these infants

Consists of gathering river stones

And of making merit stupas out of them;

The first storey is for their fathers

And the second for their mothers,

And the third makes merits for siblings

Who are at home in the land of the living;

This stupa-building is their game

During the day, but when the sun sets

A demon from hell appears, saying

“Hey! your parents back in the world

Aren’t busy doing memorial rites for you.

Their day-in, day-out grieving has in it

Much that’s cruel, sad, and wretched.

The source of your suffering down here is

That sorrow of your parents up there.

So don’t hold any grudge against me!”

With that the demon wields his black

Iron pole and smashes the children’s

Little stupas to smithereens.

Just then the much-revered Jizo

Makes an awe-inspiring entrance, telling

The children, “Your lives were short;

Now you’ve come into the realm of darkness

Very far away from the world you left.

Take me, trust me always—as your father

And as your mother in this realm.”

With that he wraps the little ones

Inside the folds of his priest robes,

Showing a wondrous compassion.

Those who can’t yet walk are helped

By him to grasp his stick with bells on top.

He draws them close to his own comforting,

Merciful skin, hugging and stroking them,

Showing a wondrous compassion.

Praise be to Life-sustaining

Bodhisattva Jizo!