Everything important about life is is important about abortion. “The Great Matter of Life and Death”—as the Zen texts put it—haunts every nuance of the battles between men and women, rich and poor, fetal rights versus mothers’ rights, or states’ rights versus federal rights. Yet the abortion debate has become so politicized and polarized that both sides view inquiry as betrayal. Politics may promise yes-or no-answers, but abortion is a no-win situation which confronts humanity with its own greatest mysteries.

Ambivalence about abortion is common, but rarely voiced; and for those women and men committed to individual rights for adults, any discussion that compromises pro-choice approaches heresy. Yet ambivalence, confusion, and conflict come with the territory, for abortion poses questions that cannot be answered by doctors, priests, senators, or moral philosophers, or settled by dogma.

“This is not an intellectual issue,” says a white middle-class therapist and former staff member of a New York City abortion clinic where the average clients were 13-year-old black girls. “I wanted to work there,” she continued. “I believed in abortion; it was a feminist issue. But the first time I witnessed an operation, something came up from deep inside me. I couldn’t take it.” After three months, she resigned but today remains a dedicated proponent of the right to choose. “In terms of a woman’s entire life, abortion is usually a pretty awful experience, but that doesn’t mean it’s the wrong choice.”

As the 1992 elections heat up, everyone wants to figure out which side to be on, but the subject of abortion demands more than that. According to Sho Ishikawa, a 32-year-old former Zen monk from Japan who currently attends Brown University, “Because of the political issue, you have to take a stand: abortion is right or wrong. But that’s just a conventional sense of right and wrong. It’s never the whole story. Especially with abortion.”

Buddhists are often asked to explain their view of abortion by those who incorrectly assume that Buddhism has its own version of papal authority. Though Buddhism has no cohesive platform, its primary views provide alternatives to the current abortion debate. In Judaism and Christianity, human life has been the focus of the biblical injunction, “Thou shalt not kill.” Like the first commandment, the first precept of the Buddhist ethical code also prohibits killing. In Buddhism, the most severe karmic consequences arise from killing humans but no form of life escapes the first precept. Buddhists take vows “to save all sentient beings.” Without doubt this includes cows and carrots. Yet there are Zen teachers who apply “sentient” to any form that comes into and passes out of this sphere of existence, and that can include non-organic objects such as teacups and toothbrushes and artworks. We vow to “save” them through care and attention.

While East-West dialogues tend to stress common values, Buddhism does offer very clear alternatives to our own anthropocentric traditions. From the all-encompassing life-view of Buddhism, the religious wing of the anti-abortion movement fails to communicate a sacred regard for creation by limiting its arguments to human life alone. When pro-life politics excludes trees, oceans, animals, or victims of AIDS, warfare, and capital punishment, religious language may amount to nothing more than slogans that play well in the media.

In the American debate, President Bush’s support for abortion in cases of rape and incest exemplifies the secular manipulation of religious sentiment. If the morality of the anti-choice platform is based on protecting the fetus, then it is illogical—and irreverent—to suggest that any fetus qualifies for the death sentence. Also, in those communities where anti-abortion sentiment prevails, these “exceptions” create their own twisted morality for those women who become pregnant through rape or incest. As witnessed by the support for Clarence Thomas and William Kennedy Smith, men and women in this society still view the violated woman as the victim of her own folly; therefore, to sanction abortion for cases of rape or incest further burdens the stigmatized woman with the responsibility of cleansing her defilement. This benign dispensation—as we are asked to see it—has nothing to do with protecting the unborn. Furthermore, the criminal, who often receives leniency in the court system, is morally censured by licensing the death of his offspring. In the name of protection we get punishment. These “exceptions” reinforce ancient patterns of control. As a necessary compromise to get votes and appear reasonable, the exceptions champion a political platform, not an objective morality. What we have here may point to an older and deeper issue: since men cannot deny to women their power to give life, they will try—as they have done historically—to deny to women the power to take it.

Pro-choice advocates also embrace the anthropocentric reliance on interpreting the “great matter of life and death” in terms of human values alone. They, too, trim the terms of debate to satisfy their constituencies. Based on a litany of sexist and secular injustices, this platform denies any dimension that threatens the political affirmation of adult rights, including the messy, emotional investigation of whether abortion is killing or not. Unfortunately, however, the public debate conditions private considerations. While denying “the great matter” may advance political success, it is detrimental to women who must face the very choice that this platform represents. Influenced by pro-choice rhetoric, too many women face “the great matter”after choosing abortion. But only in the political arena does the belief that abortion is the taking of life threaten the pro-choice platform. In actual lives and experiences it does not. For this reason, in the past few years many people, Buddhist practitioners and others, have arrived at what might be called a pro-choice/anti-abortion position.

This logic supports women’s right to choose abortion and refuses to allow the mostly male legislature to control their lives. But pro-choice/anti-abortion indicates an acceptance of how painful and problematic abortion so often is for everyone involved—parents, families, doctors, and counselors.

Not long ago, I asked a Buddhist priest how she felt about abortion. “To tell you the truth,” she whispered into the office phone of a California Zen center, “I can’t bear the idea of abortion. It makes me sick.” Asked if she would still vote pro-choice, she answered, “Absolutely. My commitment is to support pregnant women in whatever choice they make.”

Among my friends, one consistent difference keeps emerging: non-Buddhists argue, in sweeping socio-economic and historic terms, for pro-choice as the touchstone of women’s lives. But when it comes to whether or not the fetus qualifies as life, convincing dialectics often collapse into sighs and hesitation. On the other hand, Buddhist practitioners seem to accept that abortion at any stage, unequivocally, means the taking of life.

In the past year, the American Buddhist women I spoke with (from all different lineages) agreed that abortion may sometimes be necessary but is never desirable, and should never be performed without the deepest consideration of all aspects of the situation. This came from women who said that they themselves would, under no circumstances, ever have an abortion, from women who could imagine circumstances under which they would consider abortion, and from women, like myself, who have experienced abortion. All of us are currently committed to a pro-choice ballot.

For women in the vicinity of my own age (48), a pro-choice vote combined with a gut negativity toward abortion has been approached via miscalculated trials and errors—ending with both abortions and babies. At the time of my own abortion in 1960, the outlaw status of abortion defined it as another target ripe for rebellion, along with sexual mores, academic and religious institutions, lipstick, and drugs. Abortion was the precarious safety net waiting to catch the fallout from experimental forays into what we willfully called “sexual liberation.” It was our ally, ignorantly touted as a form of birth control and valued as an extension of forbidden pleasures. Abortion was no necessary evil. Many of us were for abortion.

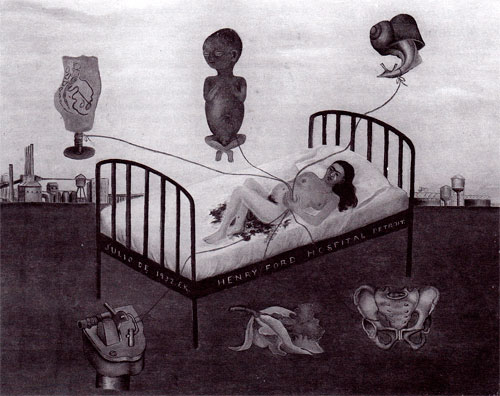

It wasn’t until my own pregnancy that I first learned from my Jewish liberal parents of the gray possibilities for abortion, that is to say, what was available in New York City south of black Harlem if you were white and not wealthy. Several alternatives were presented to me before and after my parents made sure to mention that the decision to have a baby or not was mine and that they would support my choice. My 20-year-old boyfriend had some romantic ideas about us raising kids, but he was a charming dreamer who had yet to display any interest in supporting himself, let alone a family. I don’t know now whether it was fear or reason which brought me to an abortionist’s office, but on the Monday before Thanksgiving, my older sister accompanied me to a sandstone townhouse on Lexington Avenue near 34th Street. By doctor’s orders, men were banned from the premises, and the presence of mothers discouraged. He recommended women escorts similar in age and instructed us not to loiter around the building before entering. My father came with us as far as the bank, where he handed my sister three hundred dollars in cash.

Through the haze of partial anesthesia, I remember only the invasive touch of cold metal and the muted sounds of heavy furniture being pulled across a bare floor. That, and the end of it, when the doctor, a somewhat squat and balding man, bent over the operating table to present a flaccid, shadowed cheek for a kiss of gratitude.

To grieve openly, that is, to have acknowledged, even to myself, a sense of grief, would have been admitting to a death over which to grieve. Not to mention grieving for my own involvement, or grieving for the lost possibility, or for that part of me forever gone. That it was a death, the taking of life, was not clear. Or rather, obscured and convoluted, it was all too clear. But we were different from our working class Catholic neighbors. In my non-religious and well-meaning family, there was a silent collective contract to pretend that we all understood without doubt that abortion at an early stage was not the taking of life. If the first mistake in judgment was getting pregnant at all, then the second was to participate in this denial. Apparently, this was not much comfort to other family members either: years later I would learn of my father telling my sister not long after the fact, “If I have anything to say about it there will never be another abortion in this family.”

Somewhere around 1967 or ’68, between the race riots and the anti-war protests, and the pro-abortion rallies that preceded Roe v. Wade, I vowed never to have another abortion, never to recommend one, and to stop petitioning the government to legalize abortion at home while protesting American killing in Vietnam. Though many friends told me at the time they were completely at peace with their abortions, that their experiences had left no emotional scars or moral qualms, to this day, I wonder if that’s true.

When I began reading Buddhist texts I adopted a very literal interpretation of the first precept to fortify my somewhat isolated stand against legalizing abortion. I also became a strict vegetarian. In theory, I supported individual choice even then. But I also had some Confucian-influenced idea that for the sake of cultivating a civilized society the government should not sanction killing, and that the moral obligations of society had to supercede individual needs. Therefore, to me, pro-choice meant keeping abortion illegal, with all the pernicious discrepancies between rich and poor and white and people of color—not a conclusion that I allowed myself to state at the time, but that’s what it amounted to. I could not clearly distinguish pro-choice from pro-abortion. The more literally I could apply the first precept, the more righteous I felt. In retrospect, I was more influenced by a modern sensibility in which life and death were perceived as independent force—the Creator and the Destroyer not one, not unified, not interdependent, not divine, but secularized by the very perception of separation.

My first studies in Buddhism took place at a Tibetan center where I spent time in the kitchen cooking up big pots of fatty-lined roasts for the most respected lamas. Slowly, I let up on the vegetarian diet but not on abortion. Roe v. Wade had just made history but a few of the same women who had fought for it in the name of liberation were alongside me in the kitchens of Buddhist centers. Still, I was beginning to discover that it was easier to maintain literal interpretations of the precepts if one studied texts in isolation than if one spent time in the company of teachers. I learned of herders in the isolated Tibetan plateaus whose daily sustenance depended on a cup of blood extracted from the jugular of a yak; and of yaks who “committed suicide” when their breath expired with the help of ropes lassoed around their protruding muzzles; and learned, too, about a great living lama in Nepal who spent each morning at the market buying up buckets of live fish in order to return them to the river.

A vegetarian diet may express the first precept—but only in those cultures where agriculture flourishes. For Zen monks in China and Japan, tending the gardens became an integral part of Buddhist monastic training. But in the Tibetan tradition monks are protected from even cutting down plant foods. What’s more, throughout Asia, Muslims work as animal killers and leather workers, allowing Buddhists to enjoy the benefits of dead animals while not having to kill for them. Whatever our circumstances, we are sustained by other forms of life but while dharma discourses abound on how to show compassion for cows and carrots or fleas and lice, in Buddhist cultures abortion is not openly addressed.

Then about seven or eight years ago a friend gave me a copy of John Irving’s The Cider House Rules. This Dickensian novel revolves around an orphanage which doubles as an illegal abortion clinic headed by a complicated and conscientious doctor. There, abortion was an unavoidable fact of life—not to be judged but reckoned with. In Irving’s terms, illegal abortion attests to the barbaric and humiliating treatment of women. Condemned to kitchen table abortions by an inhumane sense of justice, Irving’s women have their lives jeopardized by a society that glorifies the heroics of men at war but shames women at their most vulnerable. There was no way to justify an anti-abortion position in the name of a civilized morality.

For the first time, I became unequivocally pro-choice. And anti-abortion. Buddhist studies did not encourage pro-choice, but they did expand those perspectives on death most familiar to Westerners. In my own case, I could not find resolution in the black-and-white moral systems of my own culture. Buddhism allowed for an acceptance of that killing which is necessary to life, and of the death and the dying that inform the dimensions of a conscious life. Pro-choice can be seen as manifesting “big mind” of Buddhism, not because it promotes or condones abortion, but because it contains all possibilities, and reflects the interdependence of life and death.

It must be admitted however that there is little that relates to abortion in traditional Buddhist societies that is useful to Americans. Information regarding abortion attitudes and practices in Asia is scant. In most Asian countries, patterns of sexism are still too entrenched for women’s issues to appear on the political agenda. And nowhere has the male priesthood felt obliged to investigate interpretations of the first precept on behalf of women and the abortion issue. Abortion remains very much a women’s problem and a private matter. Women rarely discuss sex, not even with other women, and never with men. What little we know comes from doctors, hospital administrators, and representatives of world health organizations. Vietnamese women, for example, share with many women in other Asian cultures a belief that the unnamed has no consciousness. While Vietnamese priests go on record as being anti-abortion, some Buddhist women in the Vietnamese community in Boston explained to me that during the first couple of months of pregnancy, the fetus has no consciousness, no spirit and therefore, first trimester abortion is not the taking of life. This discrepancy may indicate the actual and official Buddhist versions of abortion, or it may be another instance of men attempting to regulate the lives of women.

On the other hand, in the United States an increasing number of American priests, men and women, are being called on to provide rituals or services for aborted fetuses as well as for those that miscarried. According to women who have participated in these services, much of their value lies in the opportunity to acknowledge abortion in terms of “the great matter. ”

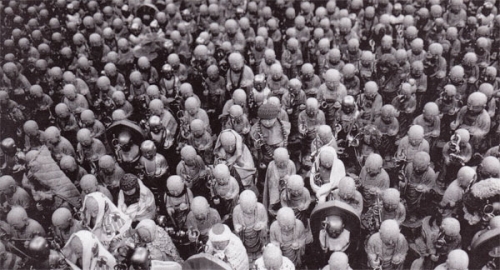

One American Zen teacher who has been performing services for aborted and miscarried babies is Robert Aitken of the Diamond Sangha in Hawaii. In his collection of essays on ethics, The Mind of Clover, Aitken Roshi discusses the Japanese Buddhist funeral for the mizuko or “water baby,” the poetical term for fetus: “Like any other human being that passes into the One, it is given a posthumous Buddhist name, and is thus identified as an individual, however incomplete, to whom we can say farewell. With this ceremony, the woman is in touch with life and death as they pass through her existence, and she finds that such basic changes are relative waves on the great ocean of true nature, which is not born and does not pass away. Bodhidharma said, ‘Self-nature is subtle and mysterious. In the realm of everlasting Dharma, not giving rise to concepts of killing is called the Precept of Not Killing.'”

In the case of Buddhist-inspired programs for homelessness, AIDS patients, or prisoners, we see the Western heritage of social responsibility merging with those Buddhist teachings that urge experiential understanding of the essential unity of the provider and the receiver. In this integration, one tradition enhances another without conflict or contradiction. When it comes to abortion, however, dharma teachings can be used to validate either pro-choice or anti-abortion politics. For this very reason, abortion places American Buddhists at the crossroads of Western and Eastern perceptions of the individual, society, and what liberation is all about. Anyone considering abortion from Buddhist teachings—and not from political peer pressure—is thrown back again and again on interpretation and view, on self-analysis and ambiguity. This in itself is Buddhism at its most instructive, demanding an authentic confrontation with oneself.

Indra’s Net, as described in the Avatamsaka Sutra, suggests that every particular manifestation of life is necessary to the whole fabric. Every phenomenon has the capacity to illuminate, contain, and reflect the entirety. Nothing exists outside this Net of Indra. Nothing can be left out because of personal preference or moral judgement. And the texts are very precise on the all-inclusive nature of this view, as difficult as it is to come to terms with, for it includes babies and bunny rabbits, lovers and teacups, radios and parents, as well as nuclear bombs, abortions and Hitler. To experience all phenomena without judgment, with neither aversion nor attraction, is what some Buddhist masters speak of as “what is.” This points to a view of “self” which has always been, and will always be, formless, not contained by skin, not structured by bone. The emphasis in Buddhist practice is to apprehend this reality through meditation, and therefore know it internally. But we struggle not just to realize ourselves as impermanent manifestations of the unborn and undying in an impartial universe. We take vows to be where the suffering is. In terms of abortion, this means staying open to the suffering of a woman faced with an unwanted pregnancy, to her lover who may or may not want the child, to the suffering of an aborted fetus, to the suffering of an unwanted baby.

In Buddhism we say there is no birth, no death, no dying, no cessation of dying. Zen master Dogen tells us that wood is wood and ash is ash and wood does not turn into ash. So life is life and death is death and life does not turn into death. All forms manifest what is; gross distinctions between life and death are labels of convenience—useful perhaps, but with no basis in reality. Writing on the Ten Grave Precepts, Robert Aitken opens a discussion on the first precept with: “There is fundamentally no birth and no death as we die and are born. When we kill the spirit that may realize this fact, we are violating this precept.”

If the essential nature of all phenomena is emptiness, who dies? Who kills? Who is killed and who is reborn? These are the great questions of Buddhist dharma and address the absolute nature of reality. Introducing the absolute dimension to the abortion issue doesn’t easily translate into a political agenda. But neither does it serve us well to hold the absolute at bay for fear of misinterpretation. What happens to the question of abortion when, even intellectually, we apprehend that everything is the enlightened way, realized or not, aborted or not? What happens in the big view?

“Life is life recycling itself all the time,” says Sylvia Boorstein. A grandmother of four, Boorstein feels fortunate that she herself has never had to face the decision whether or not to abort. As a vipassana teacher, however, she is often called upon to comfort women who come into retreat following an abortion. “What counts,” explains Boorstein, “is pro-carefulness. Pro-contraception. Pro-attention, pro-thoughtfulness. Pro-thoughtfulness with regard to sex is an expression of a sexuality that is non-exploitative, not compulsive. There is a way to have a compassionate abortion that involves the recognition that this is not the right time for this plant to flourish. But also, life is nothing but continual change and flux, with no beginning and no ending and, from the big view, it really doesn’t matter where life appears to stop and where life appears to start.”

When asked about abortion at a conference some six or seven years ago, His Holiness the Dalai Lama spoke of it as a violation of the first precept. But he added, sometimes circumstances are such that abortion can result from a compassionate decision.

Many years ago an American couple, unmarried and young, consulted their Tibetan lama when the woman became pregnant. For them, abortion was one option. But, said the lama, “How can you even consider taking a life when you have taken the bodhisattva vow to save all sentient beings?” The lama then told them that if, for any reason, they found themselves unable to care for the child once it came into the world, he himself would raise it.

According to Buddhist teachings, the chances of being exposed to true dharma are less likely than the chances of a sea turtle placing its head through the one and only yoke floating in all the ocean waters of the world; any dharma student who has an abortion automatically denies this extraordinarily rare and precious opportunity. Just to attain a human birth at all is considered a cause for celebration, for only in this life form can a sentient being realize its own true nature—which is to say, become enlightened. At the same time, Buddhist teachers also speak of the capacity of those who have passed from this sphere of existence to choose their next set of parents, and therefore participate in addressing their own karmic needs. Presumably this includes choosing wombs that carry to term and those that do not.

Speaking of reality the Zen texts tell us no snowflake falls in an inappropriate place. No exceptions, including wanted and unwanted, healthy, sick and aborted babies. But Zen gardens do not tolerate weeds. Do weeds have a right to live? Or unwanted fetuses? That human beings have this “right” assumes another human—or anthropocentric—argument. It has nothing to do with reality, that is, with snowflake reality. Humans have no more inherent right to live than they have the right to decide that garden weeds or livestock are born to die. This belief in the “right” to life reflects the Western impulse to control and shape reality, to project onto life values that embrace human, as well as individual, supremacy. As Joseph Schleidler, Executive Director of the Pro-Life League put it: “For those who say I can’t impose my morality on others, I say just watch me.” How difficult it is to consider that life itself may not care whether we live it or not; or take notice of our desires to be special when we are not.

Buddhist teachings emphasize that all form is essentially empty of description. Therefore, the responsibility for description falls to us. Buddhism in the West introduces the possibility that a non-anthropocentric reality can inspire universal responsibility, and that compassion can be cultivated as a way of being, and not as an attitude conditioned by personal judgment.

This has nothing to do with voting for or against abortion. It has everything to do with how any individual relates to sex, deals with pregnancy, decides whether to have an abortion or a baby. Yet, unfortunately the abortion debate reflects only a Western obsession with control, not consciousness.

Recently I spoke with a young man whose girlfriend had become pregnant. He was a Buddhist practitioner and she wasn’t: He wanted to have the baby and she didn’t. She went off to an abortion clinic with a girlfriend and he went to visit his Buddhist master and burst into tears. He was given a practice to alleviate his anxiety, his longing, and his guilt. I asked if his experience would change the way he might vote on the abortion issue. After remaining quiet for a few minutes, he said, “I’m not interested in listening to politicians talk for or against life or for or against abortion. I would vote for anyone who got out there and asked ‘What is life?'”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.