Rainbow Painting

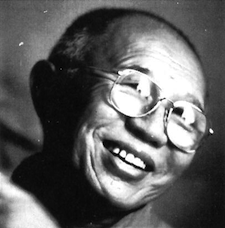

Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche

Rangjung Yeshe Publications: Hong Kong, 1995.

210 pp., $20.00 (paper).

Rainbow Painting is a compilation of teachings given in Nepal between 1991 and 1994 by the late Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche 1920-1996), the famed Tibetan Buddhist master of Kagyu Mahamudra (Great Seal) and Nyingmapa Dzogchen (Great Perfection) traditions. A handbook covering some eighteen topics, Rainbow Painting is intended as a companion volume to Tulku Urgyen’s previous work, Repeating the Words of the Buddha. Unlike that book, however, which was essentially a beginner’s text, Rainbow Painting is aimed at the more seasoned student.

In the first section, “Background,” Tulku Urgyen speaks to the issue of Vajrayana Buddhism in the current milieu. Those who are not thoroughly weather-beaten by the current climate of political correctness, which judges much of Vajrayana (particularly the special role of the teacher) as inappropriate for Western society, might welcome his view of things. Our current age is marked, he says, by a fundamental competitiveness, where people are always trying to outdo each other. According to Tulku Urgyen,

this is exactly the reason that Vajrayana is so applicable to the present era. The stronger and more forceful the disturbing emotions are, the greater the potential for recognizing our original wakefulness.

Some might argue that it is better simply to focus on the practice of calm, placid states. However, Tulku Urgyen warns that becoming intoxicated with the spiritual pleasure of peace will not help at all in realizing the awakened state. Rather, it is the “ultimate sidetrack.” The experience of great despair or fear or intense worry can be a much stronger support for practice, for “it is the intensity of emotion that allows for a more acute insight into mind essence.”

In the section “View & Nine Vehicles,” Tulku Urgyen addresses a prevalent misconception regarding the three vehicles: namely, that Mahayana is better than Hinayana, and Vajrayana is the best of all. Tulku Urgyen says unequivocally, “All these attitudes are complete nonsense.” He compares the Mahayana to a large and beautiful structure supported by the foundation of Hinayana teachings, and the Vajrayana teachings to the representations of enlightened body, speech, and mind that are housed within. The important thing, he insists, is to combine and unify all three vehicles into “a single body of practice.”

In the section entitled “The Vital Point,” the author shares valuable insights regarding the esoteric traditions of Mahamudra (Great Seal) and Dzogchen (Great Perfection). In language meant to shock us out of ordinary thought, he explains that, if you want to kill someone, the heart is the vital point. Cutting off the arms and legs will not do. “But if you stab him directly in the heart, by the time you pull the knife out your victim is already dead. If you want to kill the delusion of samsara, your weapon is the Three Words.” These refer to the three verses of Garab Dorje, the first Dzogchen master, which summarize the essence of the teaching: directly recognize the enlightened state of your own nature; resolve any doubts about it; and gain confidence in this.

According to Tulku Urgyen, once we recognize our enlightened state, there is no doubt about this good friend. We are confident we will recognize him in all circumstances whenever we meet. This means that thoughts are liberated upon recognition, like the vanishing of a drawing painted on the surface of water. The author modestly likens his words to “the chirps of a small sparrow,” but this is no ordinary bird.